We review advertisements published in the journal Actas Dermosifiliográficas between 1909 and 1939. Treatments for sexually transmitted diseases were advertised with particular frequency, and they offer a case in point that exemplifies the close relationship between the pharmaceutical industry and medical journals.

Aportamos algunos datos acerca de los anuncios publicados en la revista Actas Dermosifiliográficas durante el periodo 1909-1939. Destacan los anuncios relacionados con el tratamiento de las enfermedades de transmisión sexual. Son un ejemplo de la estrecha relación existente entre la industria farmacéutica y las revistas médicas.

We agree with Dr. Fernández Herrera y Torrelo when he said that our journal, Actas Dermosifiliográficas,is the most valuable legacy and the greatest asset of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV).1

The journal has published several articles about its own history2,3 covering a period that stretches back 102 years.

The aim of the present article is to contribute some information about the advertising that appeared in the pages of the journal during its first 30 years of publication.

Like other authors,4 we believe that advertisements are a rich source of historical information, providing us as dermatologists, in an entertaining way, a historical review of the treatments used in our specialty over the decades.

The term marketing refers to the whole process of promoting and selling a product from the moment it is created until it is purchased. This process involves many aspects and it is on these, to a greater or lesser extent, that the commercial success or failure of the product depends. Advertising is one such factor.5

An advertisement is a communication intended to convince the customer of the worth of a product.6 If we were to apply this definition to the advertisements that appear in our journal, we could say that it is advertising targeting dermatologists through the medium of a medical journal.

Advertising Between 1909 and 1936From the start of the publication of Actas Dermosifiliográficas in 1909, advertising was present in the journal and the revenue appeared in the society's books under the heading “accounts receivable.” Income from this source, which started out as 260 pesetas, had risen by 1926 to 4430 pesetas.

Initially, the list of advertisers was rather short and most of the advertisers were private individuals who provided a postal address to which physicians could apply for the products advertised rather than pharmaceutical companies as we know them today. Later, the journal started to publish a list of advertisers, which included some pharmaceutical companies, their business addresses, and the products they sold.

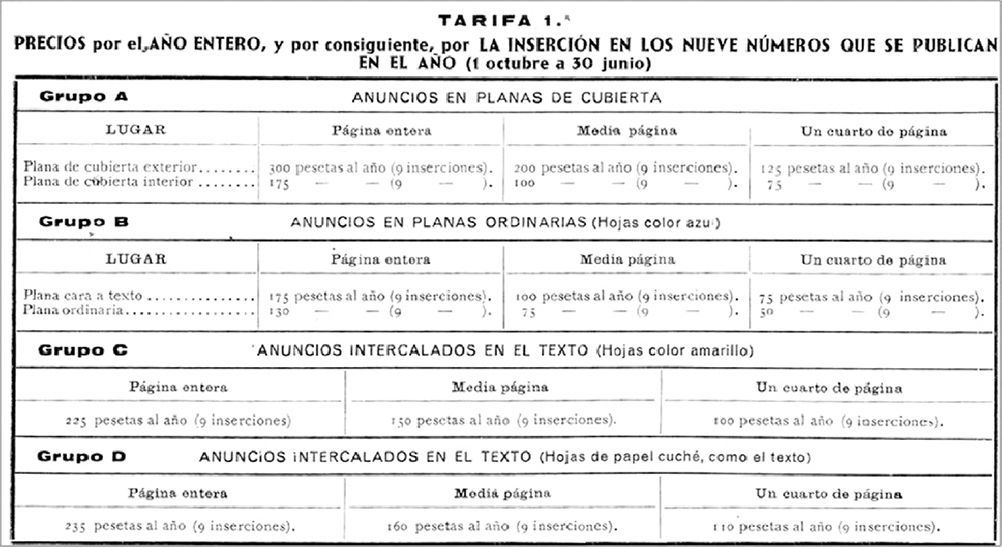

In 1932, the Academy's Board of Directors decided to modify the advertising rates and created a new scale with different prices for different types of advertisements depending on where they appeared in the journal (front cover, full page, set in text, display format, etc.) (Fig. 1).

In addition to the new scale for advertising, a second rate sheet was produced (called “the 2nd”), which listed the prices for loose inserts (blue or yellow sheets). Very few of these inserts survived when the journals were bound into the volumes now archived in the Academy's library.

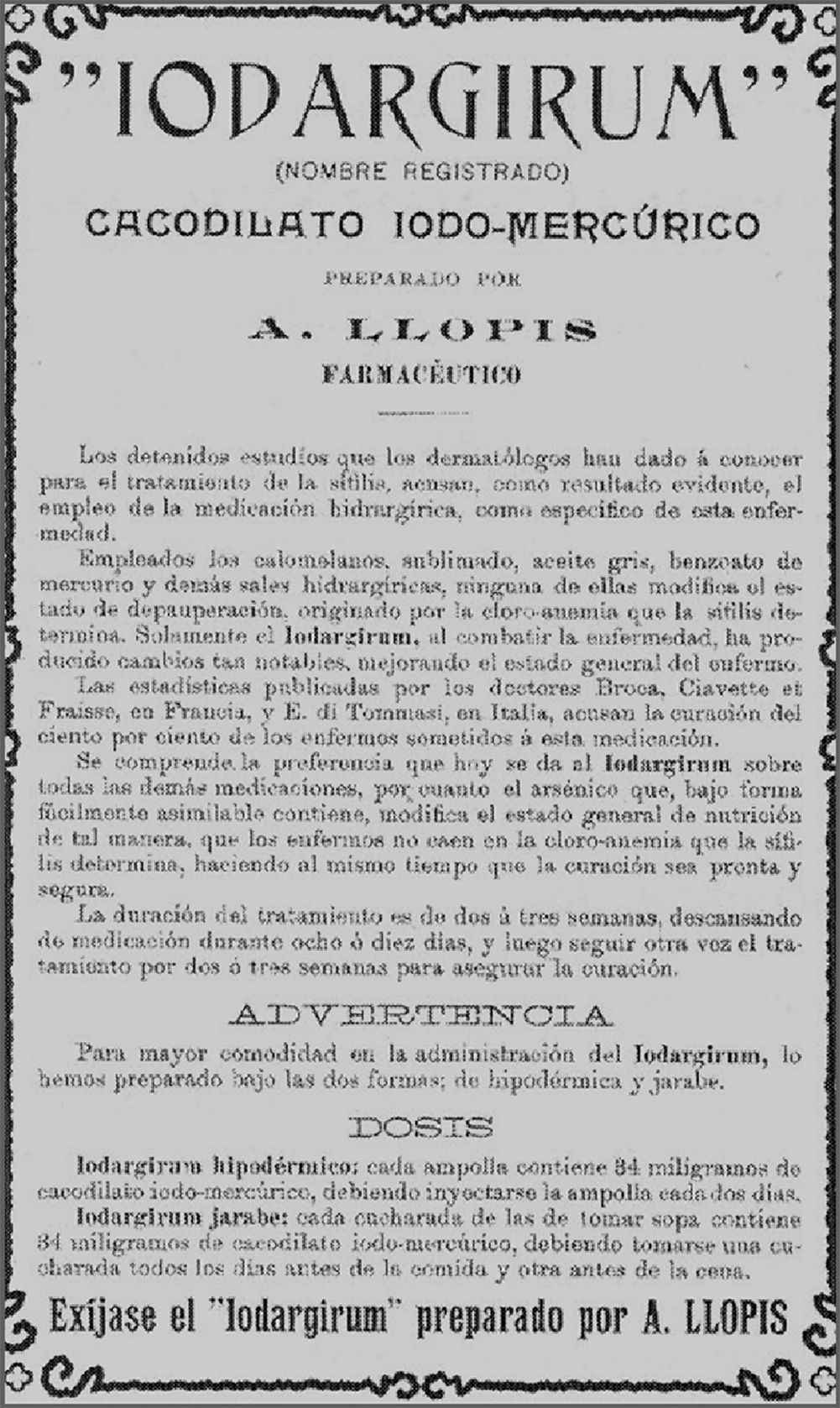

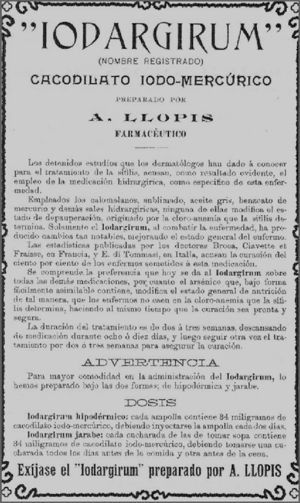

The oldest advertisement that appears in the archive refers to “Iodargirum”, a preparation of iodo-cacodylate of mercury sold by the pharmacist Mr. Llopis (Fig. 2).

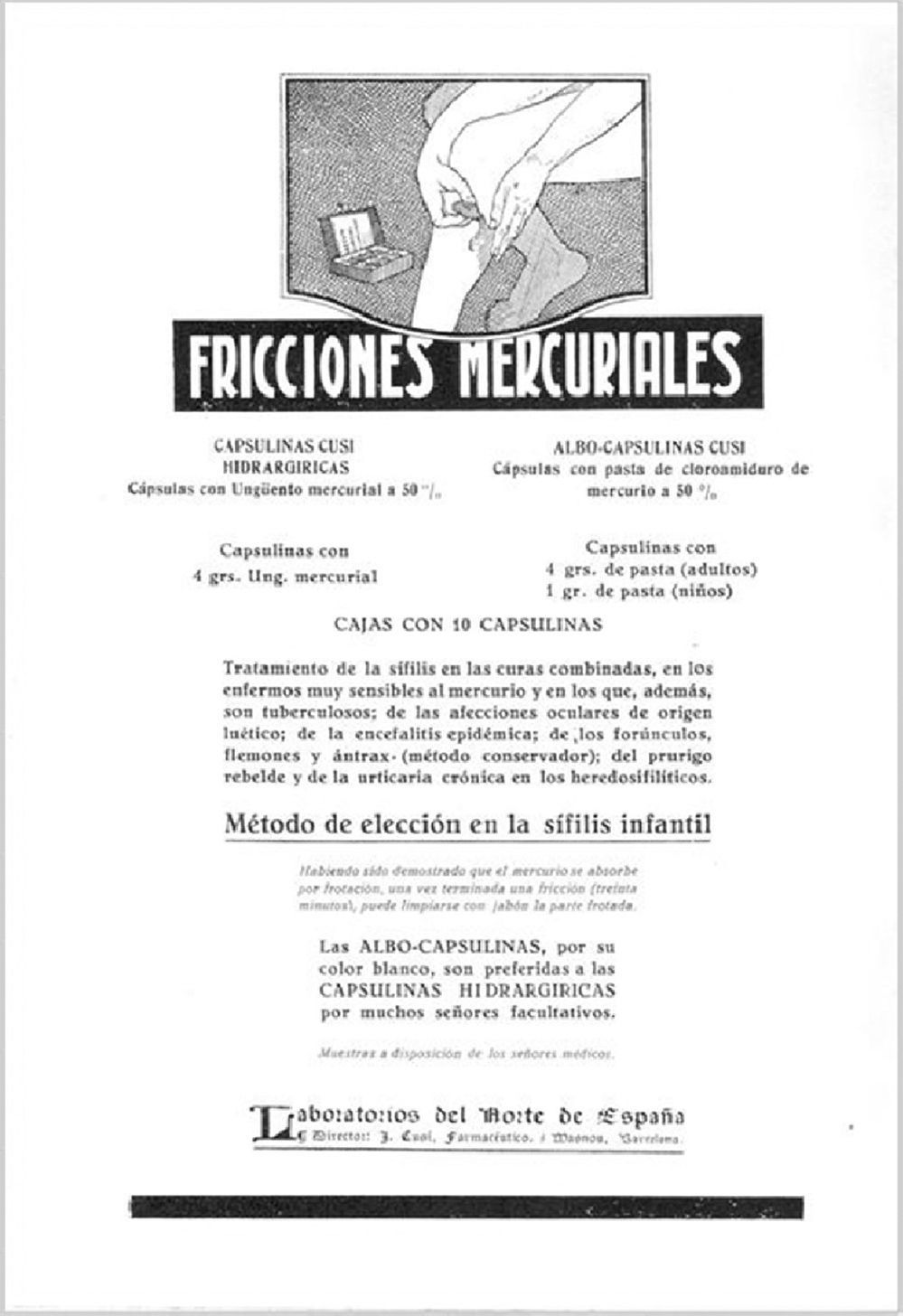

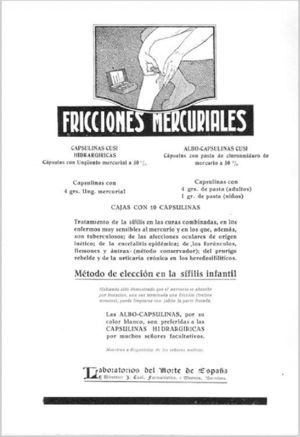

Our review of the advertising published during this period reveals that the products most often advertised were those related to the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, a finding that agrees with the observation of another author.4 This predominance is logical when we take into account that the diagnosis and treatment of venereal diseases constituted a large part of the professional activity of dermatologists in the first third of the last century.7 Advertisements can be found for arsenic compounds, different bismuth compounds for parenteral use, and drugs that combined bismuth, mercury, and arsenic. Also common were advertisements for oral and topical arsenic preparations (Fig. 3).

Before the Civil War, some pharmaceutical representatives in Spain, such as Robert Soyer, offered dermatologists a wide variety of products for the treatment of patients with tuberculosis, syphilis, and leprosy.

Given its importance in dermatological practice, topical therapy deserves special mention.

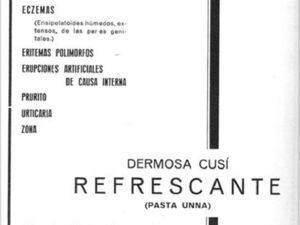

The topical armamentarium in this era was dominated by a series of products called the Dermosas (Fig. 4). These were manufactured by a company in northern Spain run by the pharmacist Joaquim Cusí y Fortunet, who founded a family business selling medical products in 1902. Armed with these Dermosas, the dermatologists of the day could try to cure a wide variety of skin conditions. Cusí produced a Dermosa for the treatment of eczema containing Dohi paste, a compound named after Professor Keizo Dohi that comprised a mixture of tar, sulfur, and zinc oxide in a fatty excipient. Pyodermas were treated with the chloramine-based Dermosas Clorazin and Dercusan. Dermatologists also prescribed all-purpose topical treatments that could be used to treat any kind of dermatitis. These included the zinc, oxymercuric, and “refreshing” Dermosas, the last of which was a formula devised by Paul Gerson Unna. After application, depending on the case, dressing with Cusí’s waxed mesh or hydrophilic gauze or cotton was recommended.

The Period Between 1936 and 1939In the closing months of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), advertisements for cosmetics start to appear, including a hair setting lotion called NEOFIX and an advertisement for Perfumería GAL S.A. featuring a text clearly influenced by the political context of the time.

Advertisements for the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases continue to predominate. These included, Novarsenobenzol (Billon) and an oral arsenic compound, both sold by the Societé Parisienne d’Expansion Chimique (SPECIA)—a predecessor of the pharmaceutical company Rhone-Poulenc—who advertised them with the inducement “included in the standard order of the military health authorities.”

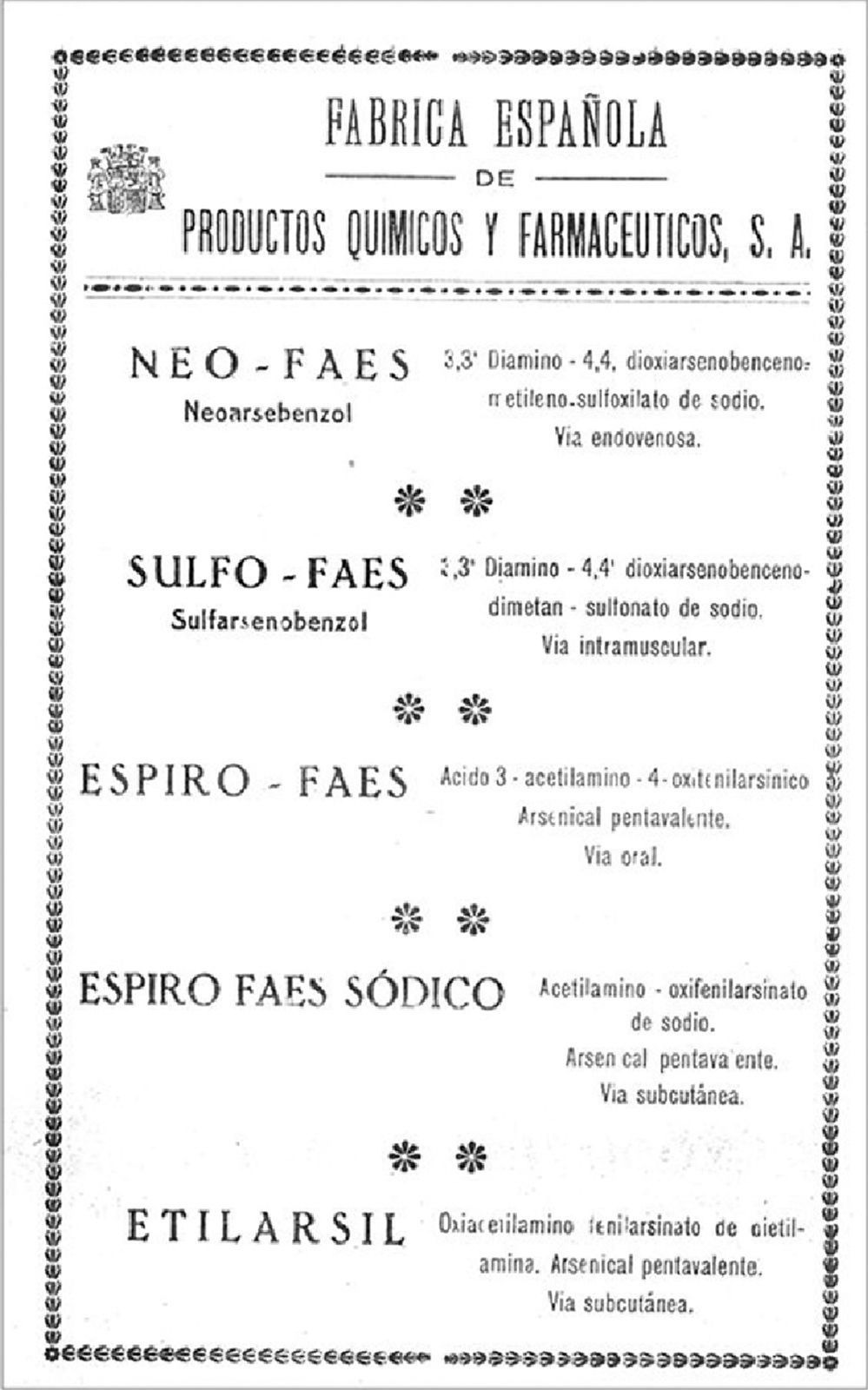

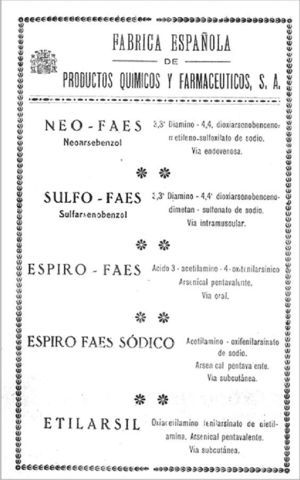

The same period saw the emergence of the arsenobenzenes, manufactured in Spain by the Fábrica Española de Productos Químicos y Farmacéuticos, S.A. (FAES) (Fig. 5) and in Italy by the Istituto Chemioterapico Italiano (ICI) in Florence.

Laboratorios Cántabro de Santander advertised Hiposulfin, a product based on sodium thiosulfate that was used as a solvent in the treatment of patients intolerant to arsenobenzols. The company made the point in its advertisements that the product was “as cheap as double-distilled water.”

Laboratorios Gil in Seville—a precursor of Farmacia “El Globo”—promoted Espirogil, a double iodide of bismuth and quinine, with the advertised advantage that the treatment was painless, although they added the recommendation “soak in hot water to facilitate injection.”

Advertisement of bismuth-based compounds proliferated, with an interesting note on one from Laboratorios Pons a company located in the town of Lerida (present-day Lleida) indicating that the company has temporarily relocated due to the war when citing as an address “accidentally: Hotel Biarritz - San Sebastian).

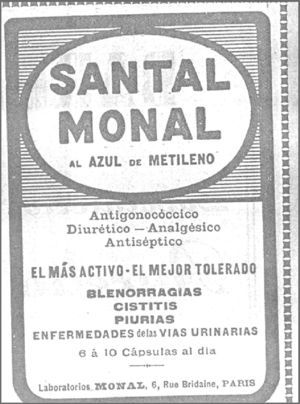

Another advertisement promotes Santal Monal imported directly from Paris for the treatment of gonorrhea (Fig. 6). This product was based on methylene blue formulated as a solution for intraurethral injection.

The soft chancre could be treated with Dmelcos, a stabilized vaccine with a concentration of 225 million of Ducrey bacilli per cm3.

At this time new topical products appear, particularly antibacterials, such as “Dermocolesterina” produced by Mazuelos of Osuna, “Bálsamo Angelical” (heavenly balm) sold by Martín Nuñez of Zamora, and “Fomentobiol” by Serva.

In short, the illustrated advertisements of the time reflect the start of a growing relationship between the pharmaceutical industry and scientific journals, which serve as a channel for marketing their products to professionals. This relationship, which still continues today, has become a mainstay both for the industry and for the economic viability of medical journals. The products advertised, almost all outdated today, also clearly reflect the therapeutic developments of the time, when they represented a qualitative leap in treatment. Finally, the advertising provides a window onto the social and political conditions of the era and the role of dermatologists, who mainly devoted their time to the management of sexually transmitted diseases.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Díaz-Díaz R. Publicidad en Actas Dermosifiliográficas (1909-1939). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:367–370.