Chronic urticaria is a difficult-to-treat skin disorder that has a major impact on patient quality of life. The latest update of the European guideline on the management of urticaria was published in 2018. In this consensus statement, produced in the autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain, we describe a multidisciplinary approach for applying the new treatment algorithm proposed by the European guideline in our region.

La urticaria crónica es una enfermedad de la piel difícil de tratar que presenta un alto impacto negativo en la calidad de vida de los pacientes. La última actualización de la guía Europea para el manejo del paciente con urticaria se publicó en 2018. Con el actual contexto, presentamos un enfoque multidisciplinar para la aplicación del nuevo algoritmo de tratamiento propuesto por la guía en el territorio español, más concretamente, en la comunidad autónoma de Andalucía.

Chronic urticaria (CU) is a serious skin disorder characterized by the spontaneous appearance of hives with or without angioedema that last for at least 6 weeks.1 The disease affects an estimated 0.5% to 1% of the general population and has an annual incidence of 1.4%.2 In Europe, over 5 million people have persistent urticaria symptoms.3

CU is associated with depression, stress, and sleep problems.4–6 Because of its negative impact on patient quality of life and health care costs, it is essential to provide patients with rapid and complete relief from symptoms and to initiate correct treatment as promptly as possible.6,7

In view of the significant regulatory variability in our region, the high costs generated by CU, and the considerable impact this disease has on quality of life, there is a need for consensus on the diagnosis, management, and treatment of CU to unify practice in hospitals and among specialists. The aim of this study was to produce an updated consensus statement adapted to the routine care of CU patients in Andalusia aimed at standardizing treatment and management strategies across hospitals in the region and among different dermatology and allergology specialists.

MethodsTo draw up the consensus statement, a review of the literature published in MEDLINE between 2000 to 2018 was conducted using combinations of the following key words: “angioedema”, “urticaria”, “CU”, “nonresponder”, “management”, “ciclosporin”, “activity”, “antihistamines”, “omalizumab”, “CSU”, “symptoms”, “diagnosis”, “comorbidities”, “tools”, “guidelines”, and “Andalusia”. A collaborative meeting, sponsored by Novartis Farmacéutica SA, was then organized in Antequera, Andalusia to bring together a multidisciplinary panel of experts in the management and treatment of CU. The panel consisted of 4 allergologists and 6 dermatologists. The 10 experts discussed and reached consensus on all the aspects contained in this document using the Metaplan method. The results are expressed in percentages.

The Metaplan method is an interactive, participative approach in which participants collaborate to seek improvements or solutions to a situation they have in common.8 Sessions are led by a moderator who guides the discussions to ensure achievement of predefined goals. Conversations are generated using cards attached to pinboards visible to all participants. The idea is that by analyzing the information presented and working together, in the same place, the group reaches a consensus on the different issues posed.

Causative and Aggravating Factors and ComorbiditiesChronic urticaria has been associated with numerous causative and aggravating factors, including physical stimuli, infectious agents, drugs, and even physical and emotional stress.1

In agreement with the literature,9–16 the following comorbidities were listed as being associated with chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU): anxiety, depression, atopic dermatitis, asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, inducible CU, and impaired work performance. Aggravating factors mentioned included use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), stress, viral infections, and alcohol consumption.

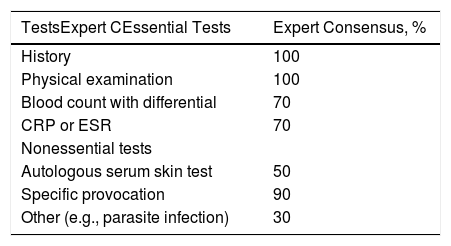

DiagnosisAccording to the latest update of the European clinical guidelines on CU,1 the diagnostic workup should be simple, useful, cost-effective, and based on patient history and physical examination. The only additional tests recommended are a differential blood count and one of the 2 acute-phase factors: erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP). History taking should focus on clinical factors associated with a poor prognosis, such as angioedema, inducible CU, association or worsening with NSAIDS, inadequate treatment response, and previous treatment failure.

Overall, 100% of the members of the expert panel considered that history taking and physical examination were essential for the diagnostic workup; 70% considered that a differential blood count and CRP or ESR testing were essential, and 90% considered that provocation tests were unnecessary (Table 1).

Routine Tests for Patients With Chronic Spontaneous Urticaria.

| TestsExpert CEssential Tests | Expert Consensus, % |

|---|---|

| History | 100 |

| Physical examination | 100 |

| Blood count with differential | 70 |

| CRP or ESR | 70 |

| Nonessential tests | |

| Autologous serum skin test | 50 |

| Specific provocation | 90 |

| Other (e.g., parasite infection) | 30 |

Abbreviations: CRP, C-reactive protein: ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Different studies have reported diagnostic delays in CSU and failure to use validated scales to classify patients and assess impact on quality of life and daily activities.17,18 The European guidelines recommend the use of activity and quality of life scales during initial clinical assessment, after starting or changing treatment, and in patients with poor disease control.1

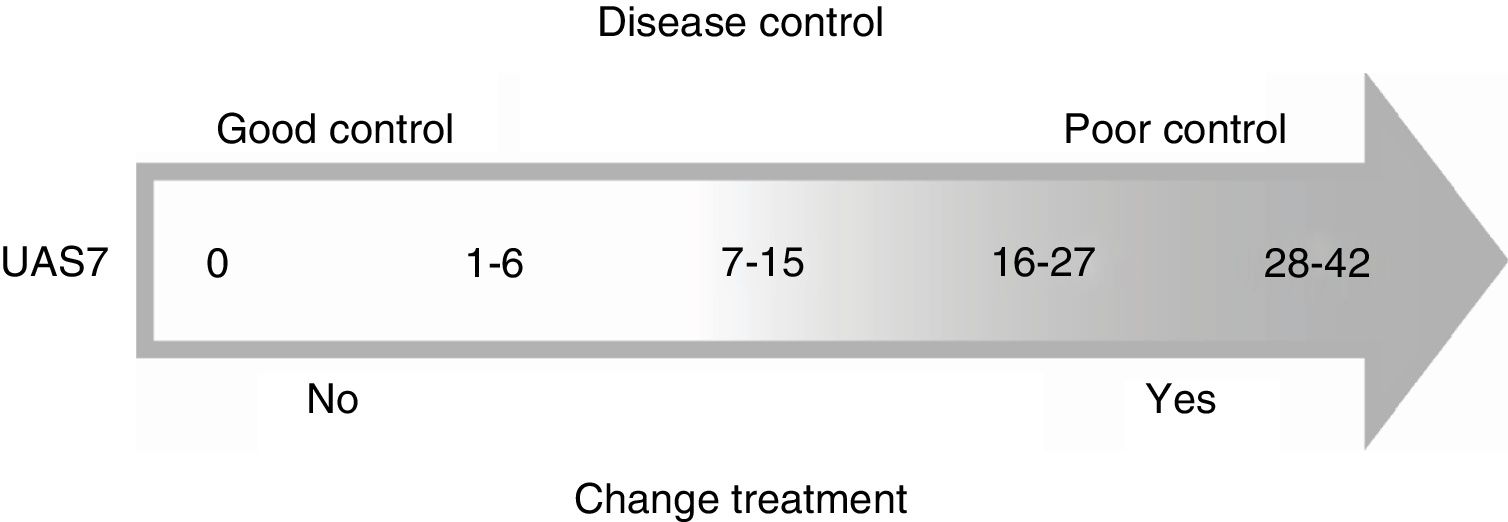

The Urticaria Activity Score 7 (UAS7), which assesses aspects of the patient’s disease over the preceding 7 days, is recommended for evaluating disease activity in CSU.1,19,20 The Spanish versions of the UAS and UAS7 were validated for diagnostic and follow-up use in the EVALUAS study.21

Other tools are the Angioedema Activity Score22 and, to quantify disease control in all types of CU (spontaneous or inducible), the Urticaria Control Test.22,23

Ninety percent of the experts considered that the UAS7 was essential for monitoring disease activity and control in patients with CSU, while a respective 50% and 40% considered that the Angioedema Activity Score and Urticaria Control Test were essential (Appendix B, Appendix, Table 1).

The UAS7 is a self-administered questionnaire and correlates well with the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).24,25

According to the European guidelines, the goal of treatment should be to achieve complete control of physical signs and symptoms without compromising patient safety and quality of life.1

The experts agreed that a UAS7 score of 7 or under indicated good disease control, while a score of over 7 indicated poor control and the need to switch treatment (Fig. 1).

Following guideline recommendations, a full assessment must include evaluation of the impact of CSU on patient quality of life. The only questionnaire currently available for specifically measuring quality of life in patients with CU is the Chronic Urticaria Quality of Life Questionnaire (CU-Q2oL) (Fig. 2).

Thirty percent of the experts considered that the DLQI was essential for assessing quality of life in patients with CSU; 60% considered that the CU-Q2oL was necessary in certain cases, and another 60% considered that the Angioedema Quality of Life Questionnaire was never necessary.

Finally, 80% of experts did not consider it necessary to assess disease activity, quality of life, or disease control at every visit.

Association With Other Types of UrticariaSeveral studies have shown an association between CU and different forms of inducible urticaria, highlighting the importance of managing triggers, as patients with associated angioedema or physical or inducible urticaria appear to respond worse to treatment.26,27

The experts agreed that CSU was associated with inducible urticaria in 45% of cases and that delayed pressure urticaria was very common. They also agreed that many patients with CSU subsequently develop inducible urticaria (e.g., cholinergic or solar urticaria). The most common inducible forms of urticaria seen in clinical practice are dermographism, solar urticaria, and cholinergic urticaria in patients with atopic dermatitis.

According to data published to date, approximately 40% of patients with CU develop angioedema.26,28

TreatmentTreatment of CSU consists of avoidance of identified triggers and administration of drugs to control symptoms.1 The guidelines recommend second-generation H1 antihistamines as first-line therapy for symptom control in CSU.1,20 Approximately 50% of patients, however, remain symptomatic despite treatment with antihistamines.22 The recommended second-line strategy is to increase the standard dose of antihistamines up to 4-fold.1

If this fails, omalizumab and ciclosporin A can be added as third- and fourth-line options respectively. The guidelines recommend a short course of oral corticosteroids lasting no longer than 10 days for patients who experience exacerbations.1

The experts were asked to rate their level of agreement/disagreement with the proposed treatment algorithm in the updated European CU guidelines on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 corresponded to completely disagree and 10 to completely agree; 50% gave a score of 9/10 (complete agreement), 40% gave a score of 8/10, and 10% gave a score of 7/10 (Appendix B, Table 2).

AntihistaminesFirst-generation H1 antihistamines are not recommended for CU as they have poor selectivity, penetrate the blood-brain barrier, and have a high number of adverse effects.29–32

All 10 experts considered that second-generation antihistamines used continuously were the first-line therapy for CU, followed by antihistamines at 2 or 4 times the standard dose as second-line therapy.

Their decision was based on guideline recommendations and on data from several studies that have demonstrated the effectiveness and safety of H1 antihistamines administered at doses 4 times higher than conventional doses.33–36 The results of one Spanish study show that 74% of patients responded to H1 antihistamines administered in accordance with the guideline recommendations.37 The same study found that angioedema, antithyroid antibodies, and the autologous serum skin test were all significantly associated with a lack of response to antihistamines.

All the experts agreed on the need to switch treatments in nonresponders to H1 antihistamines but they used a shorter dose-escalation period than that recommended in the European algorithm,1 which they viewed as too long. In ideal circumstances, 70% of the experts would wait for 0 to 4 weeks before changing a first-line treatment and 60% would wait for 0 to 4 weeks before changing a second-line treatment (Appendix B, Tables 3 and 4).

OmalizumabThe efficacy and safety of omalizumab for the treatment of CSU was demonstrated in the pivotal phase III clinical trials ASTERIA I,38 ASTERIA II,39 and GLACIAL,40,41 which, among other measures, used UAS7 and DLQI scores to assess efficacy.

Omalizumab has also been shown to be effective and safe in real-world observational studies of patients with CSU,42–47 including a retrospective, descriptive study of 110 patients treated with omalizumab in 9 Spanish hospitals.47 Overall, 81.8% of the patients achieved a complete or significant response and just 7.2% showed no response. In addition, 60% remained asymptomatic during treatment with omalizumab only. No serious adverse effects were reported. The authors concluded that omalizumab was an effective treatment for all subtypes of urticaria and may be the treatment of choice for antihistamine-resistant patients.47

The recent results of the XTEND-CIU study on the use of omalizumab in CSU for over 6 months showed that continued treatment prevented recurrences, improved quality of life, and reduced the number of angioedema episodes.48 The authors concluded that long-term treatment with omalizumab was effective and safe.

Drawing on the available evidence and the European guideline recommendations,1 100% of the experts agreed with the guideline recommendation that omalizumab 300 mg every 4 weeks should be the third-line option for patients with CSU as it has demonstrated efficacy and safety and is approved for use in this setting.

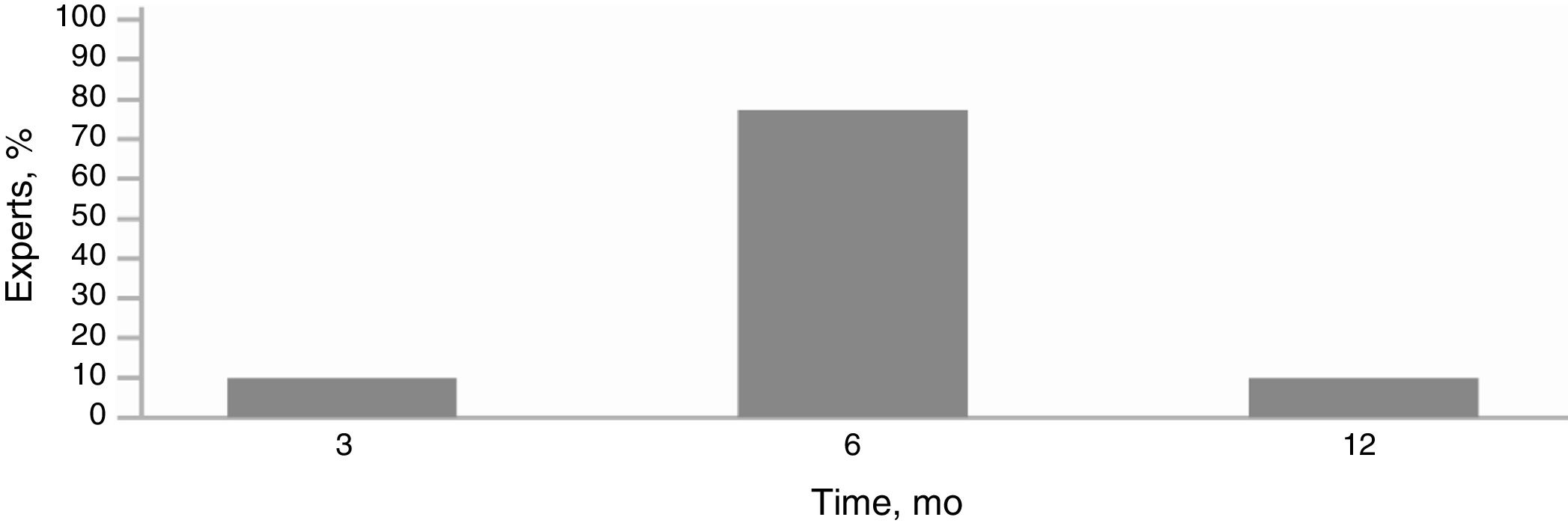

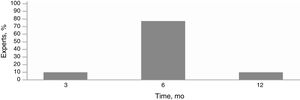

Eighty percent of the experts agreed that a patient could be considered a nonresponder if he or she did not achieve disease control after 6 months of treatment with omalizumab 300 mg every 4 weeks. The remaining 20% were of the opinion that this would be the case if there was no response after 6 months and a step-up regimen of 300-450-600 mg every 4 weeks.

When discontinuing omalizumab treatment, 90% of the experts believed it was better to reduce the dose by 150 mg every 4 weeks.

The phase IIIb OPTIMAL trial N***CT 02161562 found that almost two-thirds of patients achieved good control after 6 months of treatment with omalizumab 300 mg.49,50 Following a period of treatment withdrawal, almost 90% of patients with previously well controlled CSU regained effective control of symptoms after 12 weeks of retreatment with omalizumab.

Metz et al.51 showed that patients with CU gained complete and rapid symptom relief after reinitiation of omalizumab and withdrawal of antihistamines and did not experience any relevant adverse effects.

Ninety percent of the experts considered that patients could be retreated with omalizumab and 100% believed that it could be reintroduced at the same dose as the starting dose.

CiclosporinThe European guidelines position ciclosporin as the fourth-line treatment for nonresponders to omalizumab.1 According to its summary of product characteristics, ciclosporin is approved for the treatment of psoriasis and atopic dermatitis but not CSU.52 Its use in CSU is based on data from randomized clinical trials comparing ciclosporin with placebo and analyzing its use in combination with antihistamines.53–55 It should be noted that ciclosporin has extensive adverse effects and can be used safely for up to 2 years. It is absolutely contraindicated in pregnancy and in patients with uncontrolled hypertension or abnormal kidney function.

Most of the experts stated that they would use ciclosporin at a dose of 2.5 to 5 mg/kg to treat CSU in omalizumab-resistant patients. As routine tests, they mentioned a differential blood count, biochemistry, and kidney and liver function tests.

CorticosteroidsGuidelines recommend short-term tapering courses of corticosteroids to treat severe CU exacerbations, particularly in patients with concomitant angioedema due to the risk of secondary respiratory difficulty.1,56,57

A short course of oral corticosteroids can help reduce disease duration or activity in patients with acute urticaria or acute CSU exacerbations.58,59

The experts agreed that they would use a short, 10-day course of corticosteroids to treat exacerbations or acute episodes and apply a tapering schedule before switching to another treatment.

ConclusionsHealth care professionals treating patients with CU have access to clinical practice guidelines containing definitions, diagnostic criteria, and treatment and follow-up recommendations. In this study we found that current practices in the Andalusian health care system are very much in line with the guideline recommendations.

A multidisciplinary, guideline-driven approach to the management of patients with urticaria will help optimize health care delivery, improve quality of care and patient quality of life, and reduce the socioeconomic costs associated with suboptimal management.

Conflicts of interestAll the authors of this manuscript declare that they have received consultancy fees from Novartis.

Please cite this article as: Alcántara Villar M, Armario Hita JC, Cimbollek S, Fernández Ballesteros MD, Galán Gutiérrez M, Hernández Montoya C et al. Revisión de las últimas novedades en el manejo del paciente con urticaria crónica: Consenso multidisciplinar de la comunidad autónoma de Andalucía. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:222–228.