Topical imiquimod has been used off-label as monotherapy or adjuvant treatment for lentigo maligna. Our aim is to describe treatment modalities, clinical outcomes, and management of recurrence in patients receiving imiquimod for lentigo maligna.

Patients from our unit with lentigo maligna or lentigo maligna melanoma treated with imiquimod 5% as monotherapy or in combination with surgery were included in this study.

Fourteen cases were recruited (85.7% lentigo maligna and 14.3% lentigo maligna melanoma). Eight patients (57.1%) received imiquimod without surgery, and six (42.9%) underwent narrow excision before beginning treatment. During the follow-up period, pigmentation reappeared in 6 patients (4 postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and 2 relapses). Relapses were managed with very narrow excision (1mm margin) and retreatment with imiquimod 5%.

All imiquimod modalities showed well-tolerated side effects and low recurrence rates, with long periods of follow-up. Imiquimod appears to be a versatile option for treating LM in suitable candidates.

Imiquimod tópico ha sido utilizado como monoterapia o tratamiento adyuvante fuera de indicación para el lentigo maligno (LM). Nuestro objetivo es describir las modalidades de tratamiento, los resultados clínicos y el manejo de la recidiva en los pacientes que reciben imiquimod para lentigo maligno.

Se incluyó en este estudio a los pacientes de nuestra unidad con lentigo maligno o lentigo maligno melanoma tratados con imiquimod 5% en régimen de monoterapia o junto con cirugía.

Se seleccionaron 14 casos (el 85,7% de lentigo maligno y el 14,3% de lentigo maligno melanoma). Ocho pacientes (57,1%) recibieron imiquimod sin cirugía, y seis (42,9%) fueron sometidos a resección antes de iniciar el tratamiento. Durante el periodo de seguimiento, reapareció la pigmentación en seis pacientes (cuatro con hiperpigmentación postinflamatoria y dos recidivas). Las recidivas fueron tratadas con un margen de resección muy estrecho (1mm) y retratamiento con imiquimod 5%.

Todas las modalidades de imiquimod reflejaron buena tolerancia de efectos secundarios y bajas tasas de recidiva. Imiquimod parece ser una opción muy versátil para tratar LM en candidatos idóneos.

Lentigo maligna (LM) is the preinvasive phase of lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM).1 Surgery is considered its standard treatment.2,3 The main non-surgical techniques for LM are radiotherapy, laser, cryotherapy, and imiquimod.2,4

Imiquimod has been used off-label for LM, as a monotherapy or adjuvant treatment.1–9 However, there is little information about immediate post-treatment signs, or the detection and management of recurrences. Our aim is to describe our patients treated with imiquimod for LM, with regard to treatment modalities, clinical outcomes, recurrences and adverse effects associated.

Patients and methodsWe included all patients from 2006 to 2019 from the Melanoma Unit of our hospital with histological confirmation of LM or LMM treated with imiquimod 5%, alone or as adjuvant.

All patients had been prescribed topical imiquimod, once a day on the lesion and 1cm around, and 1cm around the scar in excised lesions. The duration of the treatment varied from 5 to 11 weeks, at least until achieving the desired level of inflammation (erythema with erosions and crusts) and, if not, tazarotene gel 0.05% was added to increase it. One dermatologist (JB) followed the patients every two weeks during the treatment period and then every six months. At each visit, patients underwent close clinical examination, photographic controls and digital dermoscopy.

Variables collected were clinical data (sex, age, location), surgery status, imiquimod regimen, inflammatory reaction, length of follow-up, and reappearance of pigmentation (recurrence or postinflammatory hyperpigmentation).

In all cases, we informed patients that the prescription of imiquimod was off-label and the different alternative treatments available. Informed consent was obtained from all patients.

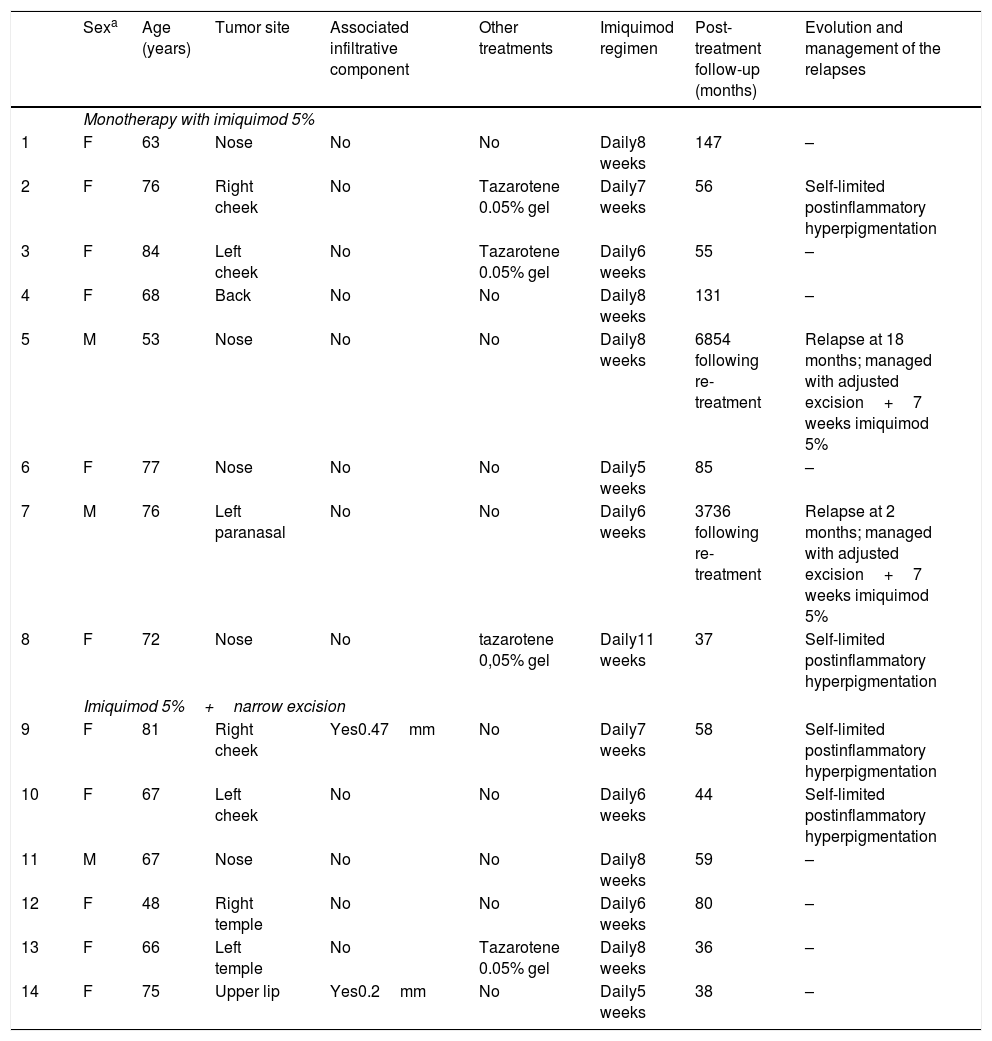

ResultsWe included 14 cases in our study. Table 1 presents sample characteristics. Eleven patients (78.6%) were women. Mean age at disease onset was 69.5 years. Lesions appeared most commonly on the nose (35.7%) and cheeks (28.6%). Twelve participants (85.7%) had a histological diagnosis of LM and two (14.3%) of LMM.

Case series of imiquimod in lentigo maligna: treatment modalities, and characteristics of the patients.

| Sexa | Age (years) | Tumor site | Associated infiltrative component | Other treatments | Imiquimod regimen | Post-treatment follow-up (months) | Evolution and management of the relapses | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monotherapy with imiquimod 5% | ||||||||

| 1 | F | 63 | Nose | No | No | Daily8 weeks | 147 | – |

| 2 | F | 76 | Right cheek | No | Tazarotene 0.05% gel | Daily7 weeks | 56 | Self-limited postinflammatory hyperpigmentation |

| 3 | F | 84 | Left cheek | No | Tazarotene 0.05% gel | Daily6 weeks | 55 | – |

| 4 | F | 68 | Back | No | No | Daily8 weeks | 131 | – |

| 5 | M | 53 | Nose | No | No | Daily8 weeks | 6854 following re-treatment | Relapse at 18 months; managed with adjusted excision+7 weeks imiquimod 5% |

| 6 | F | 77 | Nose | No | No | Daily5 weeks | 85 | – |

| 7 | M | 76 | Left paranasal | No | No | Daily6 weeks | 3736 following re-treatment | Relapse at 2 months; managed with adjusted excision+7 weeks imiquimod 5% |

| 8 | F | 72 | Nose | No | tazarotene 0,05% gel | Daily11 weeks | 37 | Self-limited postinflammatory hyperpigmentation |

| Imiquimod 5%+narrow excision | ||||||||

| 9 | F | 81 | Right cheek | Yes0.47mm | No | Daily7 weeks | 58 | Self-limited postinflammatory hyperpigmentation |

| 10 | F | 67 | Left cheek | No | No | Daily6 weeks | 44 | Self-limited postinflammatory hyperpigmentation |

| 11 | M | 67 | Nose | No | No | Daily8 weeks | 59 | – |

| 12 | F | 48 | Right temple | No | No | Daily6 weeks | 80 | – |

| 13 | F | 66 | Left temple | No | Tazarotene 0.05% gel | Daily8 weeks | 36 | – |

| 14 | F | 75 | Upper lip | Yes0.2mm | No | Daily5 weeks | 38 | – |

Eight patients (57.1%) received imiquimod without surgery. Of these, three (37.5%) required tazarotene gel 0.05%. Six patients (42.9%, 4 LM and 2 LMM) underwent narrow excision (included the infiltrative component of LMM) followed by imiquimod treatment. One patient received tazarotene.

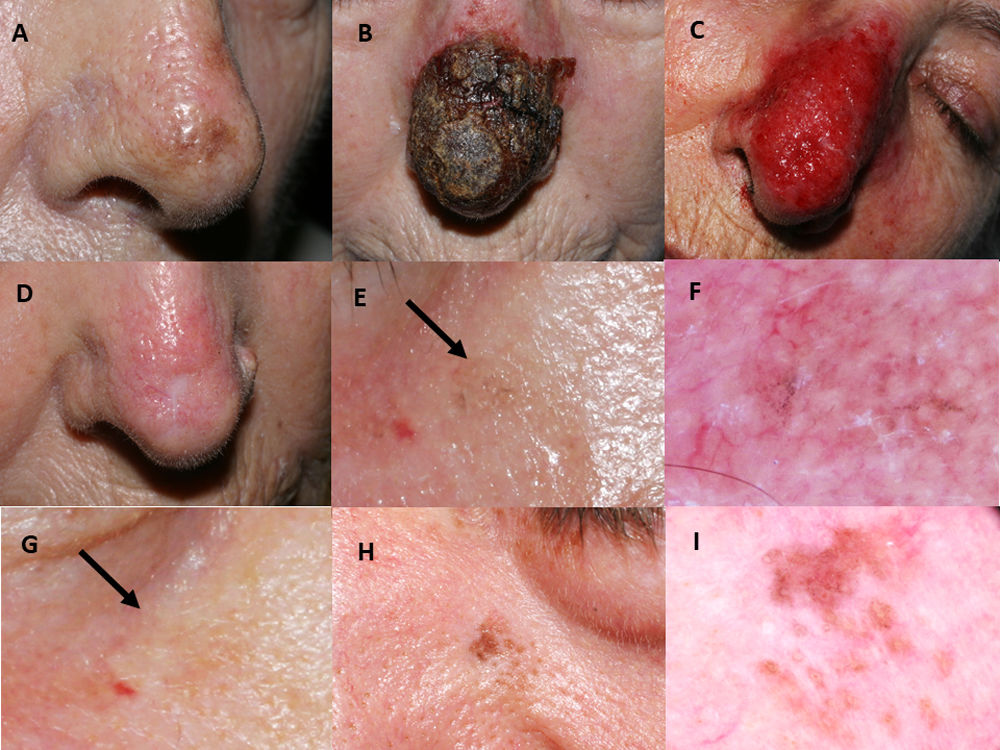

Imiquimod was applied for a mean of seven weeks. A regular adverse effect was intense erythema with crust (Fig. 1A–D). Four patients (28.6%) had a non-infectious conjunctivitis and in one case a transient ectropion due to inflammation. Solar lentigos disappeared on the treated skin.

Imiquimod treatment in a lentigo maligna located on the nasal tip in a 77-year-old female (patient 1, see Table 1): (A) Pretreatment; (B) Intense inflammatory reaction during treatment with a thick black hemorrhagic crust; (C) Intense erythema and edema after removing scabs; (D) Resolution following the end of treatment. A residual scar due to the previous skin biopsy is present. 76-year-old female, who had received treatment with 5% imiquimod in monotherapy for a lentigo maligna lesion on her right cheek with self-limited postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (patient 2, see Table 1): (E) Slight gray pigmentation, black arrow; (F) In this dermoscopic photograph, grayish annular–granular structures around the follicles (peppering); (G) Spontaneous disappearance of pigmentation after several weeks, black arrow. 76-year-old man who had a relapse of lentigo maligna at 2 months after finishing treatment with imiquimod 5% in monotherapy (patient 7, see Table 1): (H) Mottled brown pigmentation of irregular distribution on his left paranasal region; (I) Dermoscopic photograph, showing asymmetrical perifollicular brown pigmentation.

Mean post-treatment follow-up was 66.4 months. Four cases of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Fig. 1E–G) were observed and resolved spontaneously within a few weeks. Otherwise, we detected two histologically confirmed relapses, both in patients with imiquimod in monotherapy. The mean time to recurrence was 10 months. Relapses (Fig. 1H–I) were managed successfully with an excision with one millimeter margin and retreatment with imiquimod for seven weeks.

DiscussionImiquimod is not currently approved for treatment in LM, although it has been described as off label for incompletely excised lesions.2,3 Imiquimod is not a recommended monotherapy in LMM due to the risk of metastasis,3 but it is an option following excision of the infiltrative component. In our patients, imiquimod showed high efficacy in diverse treatment modalities and the recurrences observed were few (2/14 patients).

Our results are consistent with the reported data on the efficacy of imiquimod for LM. Two systematic reviews of imiquimod in monotherapy, described a clinical response rate of 78%.8,10 A systematic review of non-surgical treatments for LM, reported recurrence rates of 11.5% for radiotherapy, 24.5% for imiquimod, and 34.4% for laser therapy.4 One study with imiquimod alone or as an adjuvant treatment reported a clinical response rate of 72.7% and 94.4%, respectively.3

We think imiquimod could be useful in patients with LM who refuse a complete surgery because its unacceptable cosmetic results, or in those with comorbidities. We propose an excision of the dermoscopically visible lesion without margins; if this area is too large, we remove only the darkest area. Finally, we prescribe imiquimod 5%. Otherwise, in patients who refuse any surgery, we use imiquimod as monotherapy. The regimen of imiquimod treatment varies from 2 to 84 weeks.5,8,10 Our initial outcome was achieving an intense inflammatory reaction, and then treatment was continued for several weeks, with a total duration of 6–8 weeks. Topical tazarotene 0,05% was added when the initial inflammatory reaction was insufficient. A fortnightly follow-up with removal of the scabs during the treatment improved imiquimod absorption, reassured the patient and improved treatment compliance.

Close dermoscopic follow-up is essential to promptly detect relapses. A brownish pigmentation is suggestive of recurrence if appears in the first two years of follow-up, although in longer term, it could indicate new solar lentigos in the area. In our patients, another dermoscopic finding that oriented relapse was the perifollicular distribution of the pigmentation. A bluish-gray background is indicative of transient postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, occurs within a few weeks after treatment and it correlates histologically with melanophagia.

Reflectance confocal microscopy (RCM) is a good alternative to histological studies for monitoring the lesion. We believe that close follow-up with clinical and digital dermoscopy photography may be a valid substitute to RCM, when it is not available.

Management of an LM recurrence with imiquimod is controversial. Our series included two cases of local recurrence re-treated conservatively with narrow excision and imiquimod, with good outcomes.

The main limitations of the study include the absence of a control group, the small number of patients and the heterogeneity of treatment modalities. This restricts generalizing of our results, although real clinical practice is like this. The strengths of our study reside in that patients were followed for long period (from 3 to 12 years) by the same dermatologist, and the existence of photographic controls every 6 months for monitoring. This allowed the rapid detection of relapses and documenting the early and transient post-inflammatory changes. Our data also contributes to scientific evidence on different treatment modalities in the absence of prospective randomized clinical trials. Also, it allows clinicians to consider diverse options when wide excisions cannot be performed.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.