The practice of self-medication has experienced an increase in recent decades, with its prevalence ranging between 46% and 53.3%.1 Greater knowledge and easy access to drugs make health care personnel and medical students a particularly susceptible group for self-medication, with the potential associated risks (adverse reactions, interactions with other drugs, masking of the actual disease if diagnosis is incorrect, or posing a public health problem due to increased antibiotic resistance).2 There are few studies on self-treatment in dermatology3,4 with even fewer analyzing this practice in health science students.5–9 The main objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of self-treatment of skin lesions in medical students. Then, it sought to determine whether academic year impacted the prevalence of self-medication.

We conducted a cross-sectional descriptive study based on the responses given to an anonymous survey, conducted among medical students at Universidad de Santiago de Compostela (A Coruña, Spain). Sociodemographic data and information on the performance of self-treatment and the characteristics of this practice were collected.

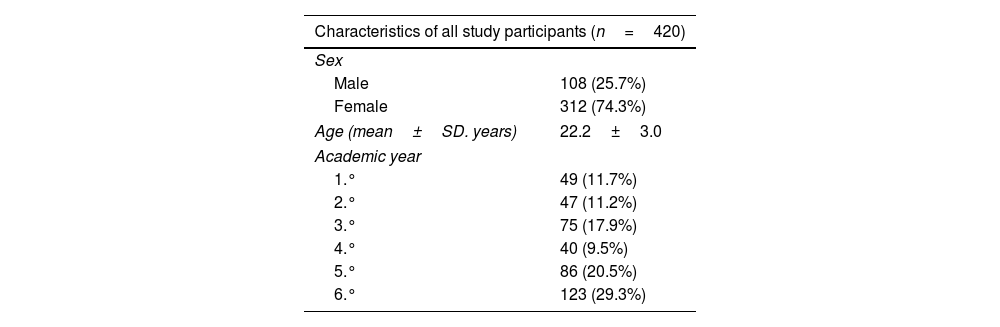

The survey was completed by 420 students (74.3% women, mean age 22.2 years). A total of 81% had self-treated for any disease on some occasion, and 51.7% had done so to treat skin lesions (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants.

| Characteristics of all study participants (n=420) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 108 (25.7%) |

| Female | 312 (74.3%) |

| Age (mean±SD. years) | 22.2±3.0 |

| Academic year | |

| 1.° | 49 (11.7%) |

| 2.° | 47 (11.2%) |

| 3.° | 75 (17.9%) |

| 4.° | 40 (9.5%) |

| 5.° | 86 (20.5%) |

| 6.° | 123 (29.3%) |

| Characteristics of the students who self-medicated | ||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of students who self-treated for any illness (n=340) | Characteristics of students who self-treated for dermatological conditions (n=217) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 86 (25.3%) | 55 (25.3%) |

| Female | 254 (74.7%) | 162 (74.7%) |

| Age (mean±SD, years) | 22.3±3.1 | 22.6±3.1 |

| Academic year | ||

| 1st | 37 (10.9%) | 18 (83%) |

| 2nd | 36 (10.6%) | 22 (10.1%) |

| 3rd | 60 (17.6%) | 34 (15.7%) |

| 4th | 33 (9.7%) | 24 (11.1%) |

| 5th | 72 (21.2%) | 50 (23.0%) |

| 6th | 102 (30.0%) | 69 (31.8%) |

SD, standard deviation.

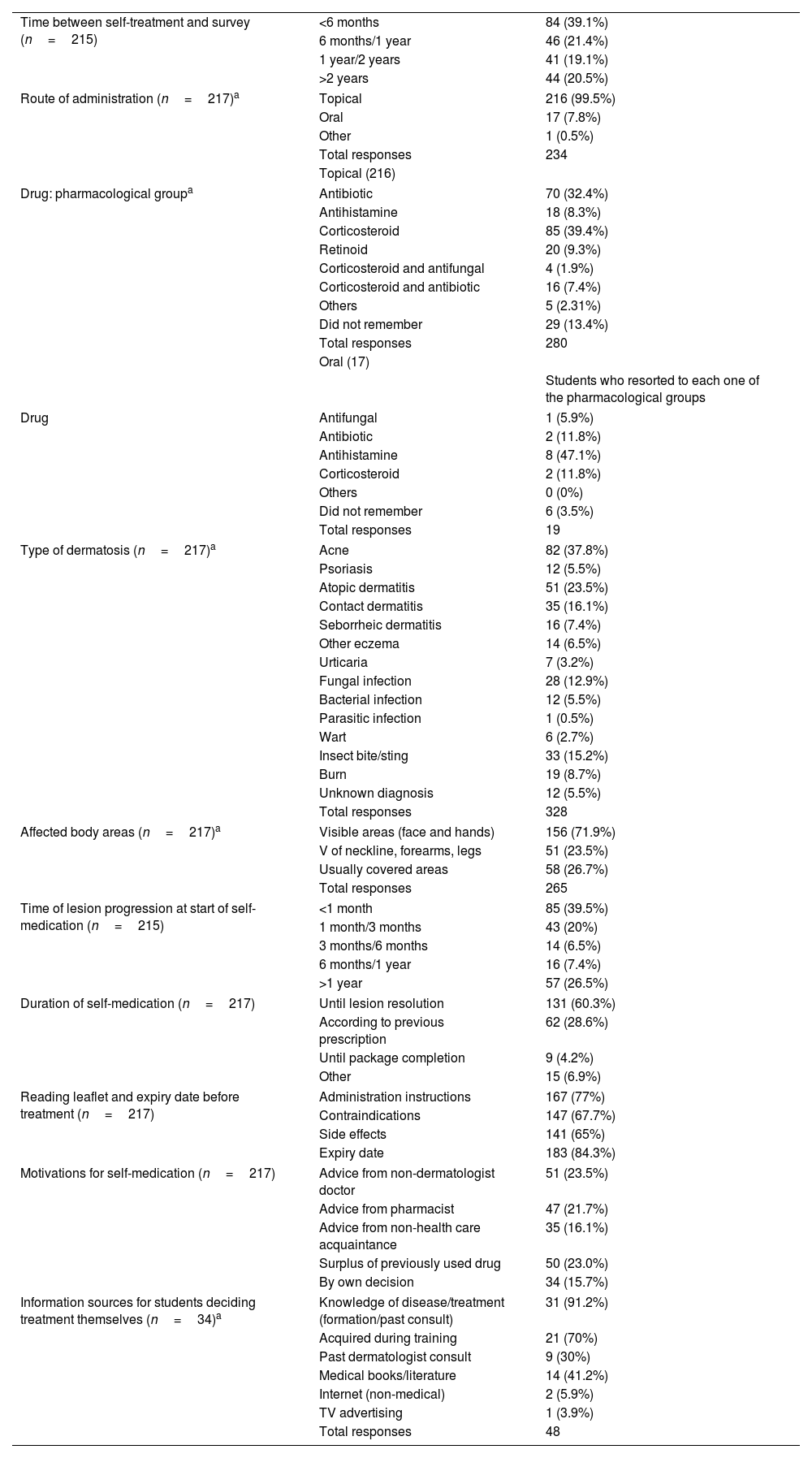

The characteristics of self-treatment for dermatological diseases are shown in Table 2. The most used route of administration was topical (99.5%), with corticosteroids standing out (39.4%), followed by antibiotics (32.4%) and antifungals (15.3%). The oral route was used by 7.8% of respondents, with antihistamines being the most represented drugs (35.3%), followed by antibiotics (11.8%) and corticosteroids (11.8%). Acne was the disease that most frequently motivated self-medication (37.8%), followed by atopic (23.5%) and contact dermatitis (16.1%). Most students used self-medication for lesions located in visible areas (71.9%), initiated self-treatment within the first month of lesion onset (39.5%), and almost two-thirds maintained it until resolution (60.3%). Most students read the package leaflet before starting treatment. The motivations that prompted self-medication were advice from a non-dermatologist physician (23.5%) or a pharmacist (21.7%), or the use of surplus previously used treatments (23.0%). The minority percentage (15.7%) chose the drug by their own decision. Of this last group, 91.2% based their decision on previous knowledge about their disease. A total of 41.5% of students who self-treated would advise another person on what treatment to apply if they had a condition similar to theirs.

Characteristics of self-treatment for dermatological diseases.

| Time between self-treatment and survey (n=215) | <6 months | 84 (39.1%) |

| 6 months/1 year | 46 (21.4%) | |

| 1 year/2 years | 41 (19.1%) | |

| >2 years | 44 (20.5%) | |

| Route of administration (n=217)a | Topical | 216 (99.5%) |

| Oral | 17 (7.8%) | |

| Other | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Total responses | 234 | |

| Topical (216) | ||

| Drug: pharmacological groupa | Antibiotic | 70 (32.4%) |

| Antihistamine | 18 (8.3%) | |

| Corticosteroid | 85 (39.4%) | |

| Retinoid | 20 (9.3%) | |

| Corticosteroid and antifungal | 4 (1.9%) | |

| Corticosteroid and antibiotic | 16 (7.4%) | |

| Others | 5 (2.31%) | |

| Did not remember | 29 (13.4%) | |

| Total responses | 280 | |

| Oral (17) | ||

| Students who resorted to each one of the pharmacological groups | ||

| Drug | Antifungal | 1 (5.9%) |

| Antibiotic | 2 (11.8%) | |

| Antihistamine | 8 (47.1%) | |

| Corticosteroid | 2 (11.8%) | |

| Others | 0 (0%) | |

| Did not remember | 6 (3.5%) | |

| Total responses | 19 | |

| Type of dermatosis (n=217)a | Acne | 82 (37.8%) |

| Psoriasis | 12 (5.5%) | |

| Atopic dermatitis | 51 (23.5%) | |

| Contact dermatitis | 35 (16.1%) | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | 16 (7.4%) | |

| Other eczema | 14 (6.5%) | |

| Urticaria | 7 (3.2%) | |

| Fungal infection | 28 (12.9%) | |

| Bacterial infection | 12 (5.5%) | |

| Parasitic infection | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Wart | 6 (2.7%) | |

| Insect bite/sting | 33 (15.2%) | |

| Burn | 19 (8.7%) | |

| Unknown diagnosis | 12 (5.5%) | |

| Total responses | 328 | |

| Affected body areas (n=217)a | Visible areas (face and hands) | 156 (71.9%) |

| V of neckline, forearms, legs | 51 (23.5%) | |

| Usually covered areas | 58 (26.7%) | |

| Total responses | 265 | |

| Time of lesion progression at start of self-medication (n=215) | <1 month | 85 (39.5%) |

| 1 month/3 months | 43 (20%) | |

| 3 months/6 months | 14 (6.5%) | |

| 6 months/1 year | 16 (7.4%) | |

| >1 year | 57 (26.5%) | |

| Duration of self-medication (n=217) | Until lesion resolution | 131 (60.3%) |

| According to previous prescription | 62 (28.6%) | |

| Until package completion | 9 (4.2%) | |

| Other | 15 (6.9%) | |

| Reading leaflet and expiry date before treatment (n=217) | Administration instructions | 167 (77%) |

| Contraindications | 147 (67.7%) | |

| Side effects | 141 (65%) | |

| Expiry date | 183 (84.3%) | |

| Motivations for self-medication (n=217) | Advice from non-dermatologist doctor | 51 (23.5%) |

| Advice from pharmacist | 47 (21.7%) | |

| Advice from non-health care acquaintance | 35 (16.1%) | |

| Surplus of previously used drug | 50 (23.0%) | |

| By own decision | 34 (15.7%) | |

| Information sources for students deciding treatment themselves (n=34)a | Knowledge of disease/treatment (formation/past consult) | 31 (91.2%) |

| Acquired during training | 21 (70%) | |

| Past dermatologist consult | 9 (30%) | |

| Medical books/literature | 14 (41.2%) | |

| Internet (non-medical) | 2 (5.9%) | |

| TV advertising | 1 (3.9%) | |

| Total responses | 48 | |

A higher prevalence of self-medication for skin lesions was observed in higher (4–6th) vs lower courses (57.4 vs. 43.3%; p=0.004). The mean age was significantly higher in students who self-treated (p<0.05 for self-medication for any reason and for dermatological lesions).

Although the published data on self-treatment for dermatological diseases are scarce, it is a common practice. A systematic review that analyzed 6 cross-sectional studies focused on self-treatment for different dermatoses in the general population observed that prevalence went from 6% up to 67.7%.3

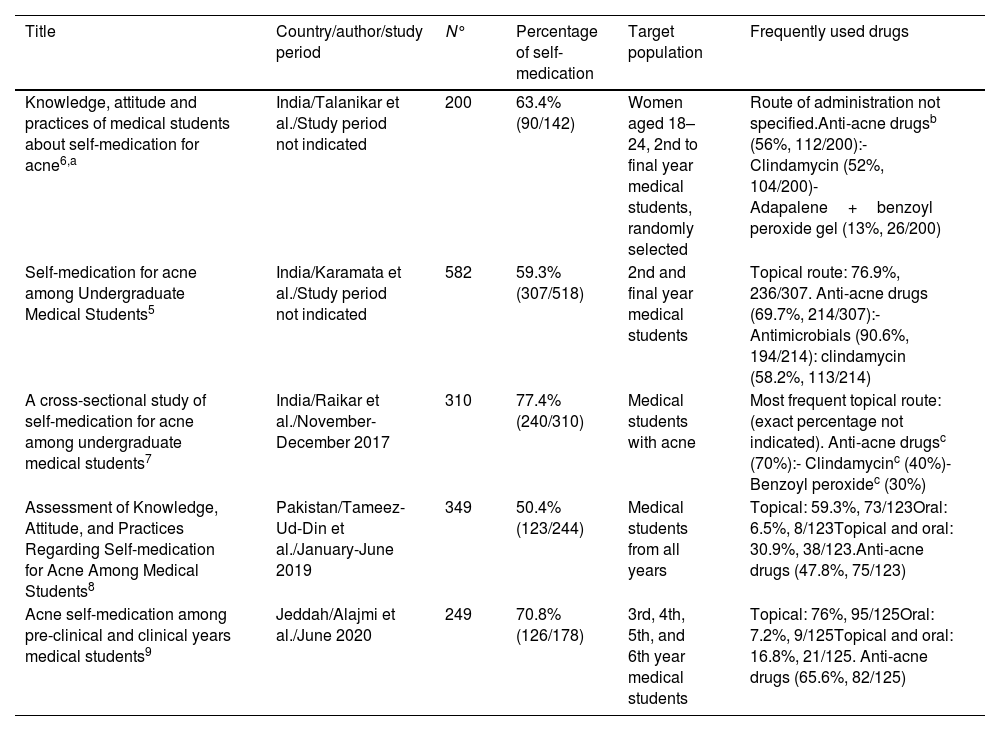

Focusing on medical students, self-medication is even more frequent. Studies that provide data on this population group (Supplementary data), observed prevalences of self-treatment for any disease between 7.32% and 100%, with 50% of the studies being >75%, which is consistent with our results (81%). In the field of self-treatment for skin lesions, studies focus on self-treatment of acne, whose prevalence went from 50.4% up to 77.4% (Table 3).5–9 As in the present study, 2 of these studies found that as the academic year increased, so did this rate.8,9 The mild nature of the disease was the main reason that prompted self-treatment in medical students with acne.5,6,8,9

Studies on self-treatment for skin lesions in medical students published in the literature.

| Title | Country/author/study period | N° | Percentage of self-medication | Target population | Frequently used drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge, attitude and practices of medical students about self-medication for acne6,a | India/Talanikar et al./Study period not indicated | 200 | 63.4% (90/142) | Women aged 18–24, 2nd to final year medical students, randomly selected | Route of administration not specified.Anti-acne drugsb (56%, 112/200):- Clindamycin (52%, 104/200)- Adapalene+benzoyl peroxide gel (13%, 26/200) |

| Self-medication for acne among Undergraduate Medical Students5 | India/Karamata et al./Study period not indicated | 582 | 59.3% (307/518) | 2nd and final year medical students | Topical route: 76.9%, 236/307. Anti-acne drugs (69.7%, 214/307):- Antimicrobials (90.6%, 194/214): clindamycin (58.2%, 113/214) |

| A cross-sectional study of self-medication for acne among undergraduate medical students7 | India/Raikar et al./November-December 2017 | 310 | 77.4% (240/310) | Medical students with acne | Most frequent topical route: (exact percentage not indicated). Anti-acne drugsc (70%):- Clindamycinc (40%)- Benzoyl peroxidec (30%) |

| Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude, and Practices Regarding Self-medication for Acne Among Medical Students8 | Pakistan/Tameez-Ud-Din et al./January-June 2019 | 349 | 50.4% (123/244) | Medical students from all years | Topical: 59.3%, 73/123Oral: 6.5%, 8/123Topical and oral: 30.9%, 38/123.Anti-acne drugs (47.8%, 75/123) |

| Acne self-medication among pre-clinical and clinical years medical students9 | Jeddah/Alajmi et al./June 2020 | 249 | 70.8% (126/178) | 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th year medical students | Topical: 76%, 95/125Oral: 7.2%, 9/125Topical and oral: 16.8%, 21/125. Anti-acne drugs (65.6%, 82/125) |

Of note, many medical students feel confident in their pharmacological knowledge, which favors self-medication and the recommendation of treatment to a third party. In the study population, 41.5% would make this recommendation, a figure that went from 26.7% up to 50% in studies on medical students with acne.5,8 This data is concerning since diagnosis and treatment may not be correct, as there is no prior dermatological consultation.

The retrospective collection of information, the evaluation of students from a single School of Medicine, and the use of a non-validated questionnaire should be highlighted as limitations of this work.

In conclusion, in the evaluated medical student population, the prevalence of self-medication for skin lesions was high, being significantly higher in students from higher courses. These findings highlight the need to increase training in medical students about the importance of adequate and rational use of dermatological drugs, instilling good practice in professional practice without trivializing the significance of a therapeutic recommendation. Similarly, greater control of dispensations without a prescription, along with the reduction in waiting lists that enable faster access to specialized consultation, would contribute to reducing self-treatment, since patient empowerment for self-control of their skin disease will make sense when there is an accurate diagnosis and therapeutic guidance from a dermatologist.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.