Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is distributed worldwide. In Spain, the prevalence is low (0.15% according to 2019 data from the Ministry of Health).1 The Eastern Mediterranean region currently has the highest prevalence of chronic hepatitis C, with 12 million cases according to WHO data.2

Although this infection might initially be considered beyond the scope of our specialty, it is relevant in our role as venereologists,3 particularly due to its possible primary or secondary effects on the skin. Skin signs most commonly associated with chronic HCV infection include mixed cryoglobulinemia, lichen planus, and porphyria cutanea tarda. Chronic pruritus and necrolytic acral erythema are conditions potentially related to HCV.4,5

Regarding its route of transmission, most patients acquire the infection through parenteral drug use (PDU).6 Transmission through blood transfusions has been reduced since donor screening began. Another risk group includes solid organ transplant recipients. HCV can also be transmitted through improper use of materials and breaches of health protocols (such as failures in aseptic techniques or reuse of syringes).7 Tattoos, piercings, or sharing personal hygiene items—like toothbrushes or other objects that may cause potential blood exposure—have been associated with its transmission. Another route of transmission is sexual. Practices like vaginal or rectal douching and vaginal or rectal fisting may increase the risk of acquiring HCV and other sexually transmitted infections.8 Anal sex—especially receptive—has also been associated with HCV infection, as it may involve greater mucosal trauma and blood exposure.9 While other routes of transmission have been described in the context of sexual relations, they are considered lower risk than those mentioned above.

In the context of venereological care, special attention should be paid to risk behaviors such as PDU, sex work, and chemsex. Previous HIV infection is also relevant, as co-infection with HCV increases the likelihood of perinatal transmission.

It is recommended for screening:

- -

If the risk situation for HCV occurred > 3 months ago: request HCV antibodies. If these are positive, the study should be completed with HCV RNA or antigen detection to confirm active infection.

- -

If it was more recent, it is recommended to directly request HCV RNA or antigen detection to detect active infection.

- -

In people living with HIV (PLWH), immunosuppressed patients, and patients with past and cured HCV infection—or eradicated through drugs—it is also recommended to directly request HCV RNA or antigen detection.

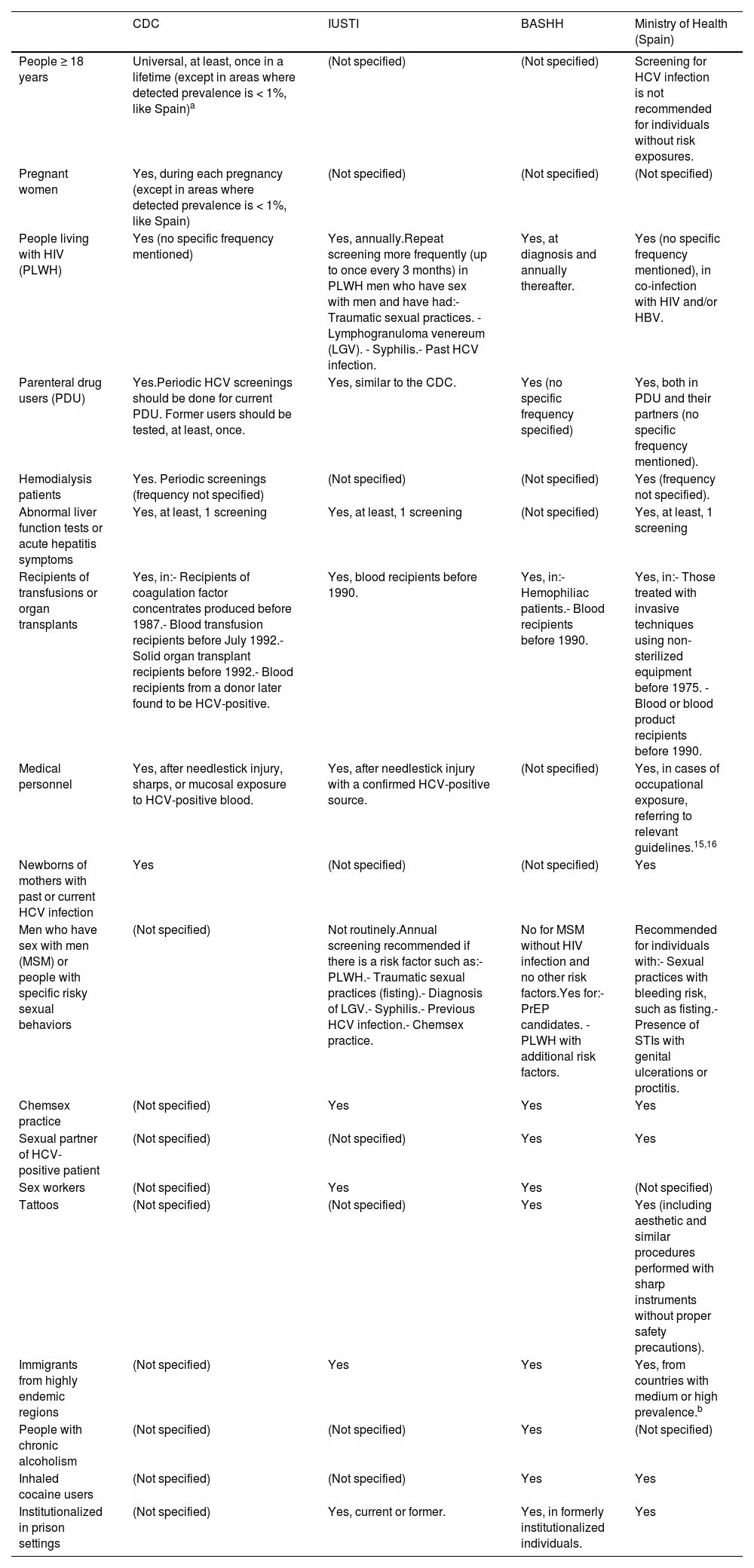

Several clinical practice guidelines include recommendations for HCV screening and its frequency. The 3 most widely used in Europe and abroad are those of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),10 the International Union against Sexually Transmitted Infections (IUSTI),11 and the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH).12 In Spain, we follow those of the Spanish Ministry of Health (MSE).13 Although the 4 guidelines share similarities, they also have some discrepancies, which deserve to be analyzed.

Recommendations of the 3 guidelines and their differences are shown in Table 1. Below, we highlight the 5 most notable ones: 1) Only the CDC guideline recommends universal screening for pregnant women and newborns of HCV-seropositive mothers. 2) The recommended frequency of screening in PLWH varies. 3) IUSTI, CDC, and MSE recommend HCV screening in cases of hepatitis symptoms or elevated liver enzymes, and after needlestick injuries among health care personnel or exposure to mucous membranes or blood from HCV-positive patients. 4) Although they agree that HCV screening is not necessary for men who have sex with men (MSM) without other risk factors, BASHH recommends it for candidates for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), while IUSTI and MSE recommend it for those who have any risk factors (Table 1). 5) Finally, IUSTI, BASHH, and MSE—not the CDC—recommend screening for people who practice chemsex, are immigrants from endemic regions, or are institutionalized in penitentiary centers.

Screening recommendations and frequency across different guidelines.

| CDC | IUSTI | BASHH | Ministry of Health (Spain) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| People ≥ 18 years | Universal, at least, once in a lifetime (except in areas where detected prevalence is < 1%, like Spain)a | (Not specified) | (Not specified) | Screening for HCV infection is not recommended for individuals without risk exposures. |

| Pregnant women | Yes, during each pregnancy (except in areas where detected prevalence is < 1%, like Spain) | (Not specified) | (Not specified) | (Not specified) |

| People living with HIV (PLWH) | Yes (no specific frequency mentioned) | Yes, annually.Repeat screening more frequently (up to once every 3 months) in PLWH men who have sex with men and have had:- Traumatic sexual practices. - Lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV). - Syphilis.- Past HCV infection. | Yes, at diagnosis and annually thereafter. | Yes (no specific frequency mentioned), in co-infection with HIV and/or HBV. |

| Parenteral drug users (PDU) | Yes.Periodic HCV screenings should be done for current PDU. Former users should be tested, at least, once. | Yes, similar to the CDC. | Yes (no specific frequency specified) | Yes, both in PDU and their partners (no specific frequency mentioned). |

| Hemodialysis patients | Yes. Periodic screenings (frequency not specified) | (Not specified) | (Not specified) | Yes (frequency not specified). |

| Abnormal liver function tests or acute hepatitis symptoms | Yes, at least, 1 screening | Yes, at least, 1 screening | (Not specified) | Yes, at least, 1 screening |

| Recipients of transfusions or organ transplants | Yes, in:- Recipients of coagulation factor concentrates produced before 1987.- Blood transfusion recipients before July 1992.- Solid organ transplant recipients before 1992.- Blood recipients from a donor later found to be HCV-positive. | Yes, blood recipients before 1990. | Yes, in:- Hemophiliac patients.- Blood recipients before 1990. | Yes, in:- Those treated with invasive techniques using non-sterilized equipment before 1975. - Blood or blood product recipients before 1990. |

| Medical personnel | Yes, after needlestick injury, sharps, or mucosal exposure to HCV-positive blood. | Yes, after needlestick injury with a confirmed HCV-positive source. | (Not specified) | Yes, in cases of occupational exposure, referring to relevant guidelines.15,16 |

| Newborns of mothers with past or current HCV infection | Yes | (Not specified) | (Not specified) | Yes |

| Men who have sex with men (MSM) or people with specific risky sexual behaviors | (Not specified) | Not routinely.Annual screening recommended if there is a risk factor such as:- PLWH.- Traumatic sexual practices (fisting).- Diagnosis of LGV.- Syphilis.- Previous HCV infection.- Chemsex practice. | No for MSM without HIV infection and no other risk factors.Yes for:- PrEP candidates. - PLWH with additional risk factors. | Recommended for individuals with:- Sexual practices with bleeding risk, such as fisting.- Presence of STIs with genital ulcerations or proctitis. |

| Chemsex practice | (Not specified) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sexual partner of HCV-positive patient | (Not specified) | (Not specified) | Yes | Yes |

| Sex workers | (Not specified) | Yes | Yes | (Not specified) |

| Tattoos | (Not specified) | (Not specified) | Yes | Yes (including aesthetic and similar procedures performed with sharp instruments without proper safety precautions). |

| Immigrants from highly endemic regions | (Not specified) | Yes | Yes | Yes, from countries with medium or high prevalence.b |

| People with chronic alcoholism | (Not specified) | (Not specified) | Yes | (Not specified) |

| Inhaled cocaine users | (Not specified) | (Not specified) | Yes | Yes |

| Institutionalized in prison settings | (Not specified) | Yes, current or former. | Yes, in formerly institutionalized individuals. | Yes |

We believe this article and its Table 1 are useful as they allow for quick consultation of the applicable guidelines in our field and highlight their similarities and discrepancies. Although Spain has a low prevalence, 1386 new HCV diagnoses were reported in 2019,14 which is why we do not overlook the appropriateness of screening in situations that require it. While extrapolation of any of the 3 guidelines to our setting seems reasonable, we can take advantage of existing differences to decide, critically and individually, what is best for each patient.

FundingNone declared.