The incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is increasing in Spain. Suppurative STIs are one of the most frequent reasons for consultation in specialized centers. The reason for suppurative STIs is multiple and their empirical treatment varies with the currently growing problem of antimicrobial resistance. Dermatologists are trained and prepared to treat these diseases, but their correct management requires active knowledge of national and international guidelines.

The present document updates, reviews and summarizes the main expert recommendations on the management and treatment of these STIs.

La incidencia de las infecciones de transmisión sexual (ITS) está aumentando en nuestro medio. Las ITS supurativas son uno de los motivos de consulta más frecuente en las consultas especializadas. La causa de las ITS supurativas es múltiple y su tratamiento empírico cambia con el aumento de las resistencias antimicrobianas. Los dermatólogos estamos formados y preparados para atender estas enfermedades, pero su manejo correcto requiere un conocimiento actual de las guías nacionales e internacionales.

Este documento actualiza, revisa y resume las principales recomendaciones de expertos sobre el manejo y tratamiento de estas ITS.

Urethritis is the most common genitourinary syndrome in sexually active men younger than 50 years old.1 The most frequent symptoms include mucoid, mucopurulent, or purulent urethral discharge (60% up to 90%), dysuria (50% up to 80%), increased urinary frequency (6%), or itching (5%); urethritis, however, can run asymptomatic.2

CervicitisCervicitis results from the inflammation of the cervix, and the most common symptoms are purulent or mucopurulent endocervical discharge visible in the endocervical canal or in an endocervical swab sample. Some women may report abnormal vaginal discharge, intermenstrual vaginal bleeding (e.g., postcoital), suprapubic abdominal pain, or dyspareunia; although it is often asymptomatic.3

Proctitis, proctocolitis, and enteritisSexually transmitted infections (STIs) affecting the anus, rectum, colon, and small intestine consist of acute or subacute inflammatory processes caused by microorganisms that can be transmitted through various sexual practices such as receptive anal sex, use of contaminated sex toys, fisting, or oro-anal sex. The incidence of these infections is increasing, with most being diagnosed in men who have sex with men (MSM), with a higher prevalence in people living with HIV (PLHIV).4–6

In proctitis, there is inflammation of the rectum, often accompanied by rectal tenesmus, anorectal or suprapubic pain, mucous or purulent anal discharge, rectal bleeding, a sensation of incomplete evacuation, or constipation. Proctitis can also be associated with fever and/or general malaise, ulcers or vesicles, edema, and erythema of the rectal mucosa; a high percentage of proctitis cases, though, are asymptomatic.

In proctocolitis, the inflammation extends beyond the rectum, and in enteritis, it affects the colon and/or small intestine. Proctocolitis can present with proctitis symptoms, colicky abdominal pain (especially in the hypogastric area), diarrhea (often with blood), and general symptoms (fever, chills, myalgias, vomiting). A person with enteritis may experience nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, colicky abdominal pain, abdominal distension, or fever, but without proctitis or proctocolitis symptoms.5

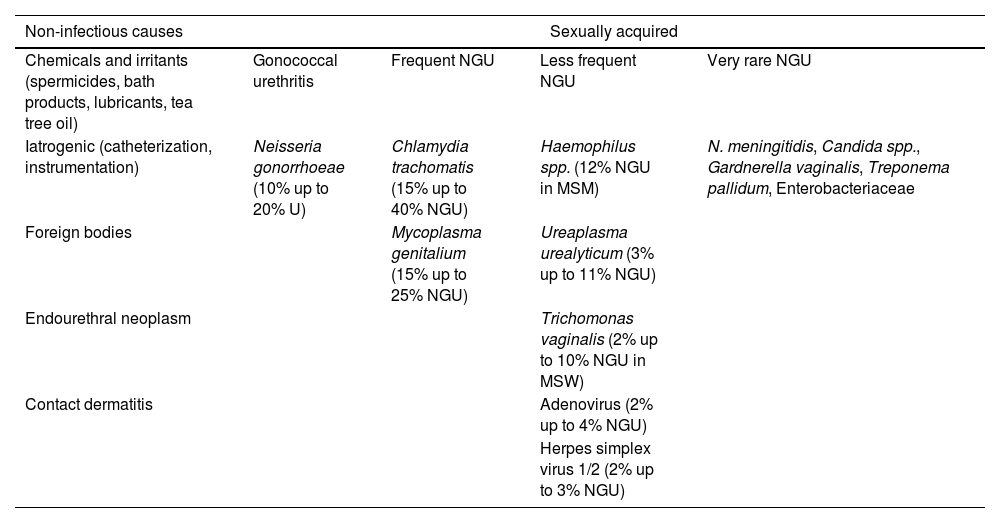

CausesEtiology of urethritisUrethritis can have multifactorial causes (Table 1),7–12 but in most cases, it is sexually acquired. When sexually acquired, urethritis is described as gonococcal urethritis (GU) if Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) is detected, or as non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU) if it is not. Its etiology varies according to the local prevalence of infectious agents. NG can account for 10% up to 20% of urethritis cases, Chlamydia trachomatis (CT) for 15% up to 40% of NGU cases, and Mycoplasma genitalium (MG) for 15% up to 25% of NGU cases.13

Etiology of urethritis.7–12

| Non-infectious causes | Sexually acquired | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemicals and irritants (spermicides, bath products, lubricants, tea tree oil) | Gonococcal urethritis | Frequent NGU | Less frequent NGU | Very rare NGU |

| Iatrogenic (catheterization, instrumentation) | Neisseria gonorrhoeae (10% up to 20% U) | Chlamydia trachomatis (15% up to 40% NGU) | Haemophilus spp. (12% NGU in MSM) | N. meningitidis, Candida spp., Gardnerella vaginalis, Treponema pallidum, Enterobacteriaceae |

| Foreign bodies | Mycoplasma genitalium (15% up to 25% NGU) | Ureaplasma urealyticum (3% up to 11% NGU) | ||

| Endourethral neoplasm | Trichomonas vaginalis (2% up to 10% NGU in MSW) | |||

| Contact dermatitis | Adenovirus (2% up to 4% NGU) | |||

| Herpes simplex virus 1/2 (2% up to 3% NGU) | ||||

MSM: men who have sex with men; MSW: men who have sex with women; U: urethritis; NGU: non-gonococcal urethritis.

Ureaplasma urealyticum is inconsistently associated with NGU and is probably not a cause unless present with a high bacterial load. In Western Europe, Trichomonas vaginalis (TV) as a cause of male urethritis is uncommon. Adenoviruses may account for 2% up to 4%, and herpes simplex virus (HSV) is an uncommon cause of NGU, although they can cause urethritis in the absence of typical genital ulcers. Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus spp., Candida spp., and others have been reported in a small proportion of NGU cases.

Of note that polymicrobial infections can be identified in up to 20% of men, and in 20% up to 30% of urethritis cases, no known pathogens are detected.13

Etiology of cervicitisCT or NG is the most common etiology of cervicitis,13 although TV, MG, and HSV—mainly HSV-2, although HSV-1 is increasingly common—have also been reported.14–17 However, in many cases of cervicitis, no microorganism is isolated, especially among women with relatively low risk of contracting STIs (e.g., women older than 30 years). Limited data suggest that bacterial vaginosis and frequent douching may cause cervicitis.18 Available data do not suggest that there is an association between group B streptococcal colonization and cervicitis, nor is there specific evidence of a role for Ureaplasma parvum or Ureaplasma urealyticum in cervicitis.19

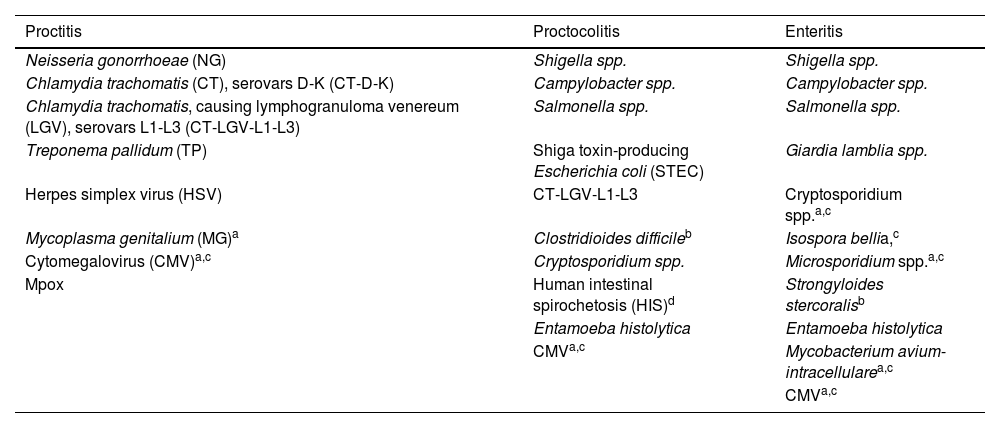

Etiology of proctitis, proctocolitis, and enteritisAlthough proctitis can be multifactorial, in most cases, it is sexually acquired.13 The main etiological agents of sexually transmitted proctitis are NG and CT. Rectal infection with MG alone is rarer and causes fewer symptoms than NG or CT.20,21 In 30% up to 40% of cases, no microorganism is identified, and in 10% of cases, more than 1 microorganism is involved.22

In the differential diagnosis of proctitis, non-infectious causes should be considered, such as medical radiation, inflammatory bowel disease, drug-related adverse effects or associated with topical products. Some traumas may occur in a sexual context (e.g., fisting practices, enemas, sex toys, drug insertion) and/or among chemsex users (substances like methamphetamines, mephedrone, or gamma-hydroxybutyrate-gamma-butyrolactone).23,24 Conversely, proctocolitis and enteritis are not always sexually acquired. The main etiology of these sexually acquired entities is shown in Table 2.

Etiology of sexually acquired proctitis, proctocolitis, and enteritis.40,70

| Proctitis | Proctocolitis | Enteritis |

|---|---|---|

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) | Shigella spp. | Shigella spp. |

| Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), serovars D-K (CT-D-K) | Campylobacter spp. | Campylobacter spp. |

| Chlamydia trachomatis, causing lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), serovars L1-L3 (CT-LGV-L1-L3) | Salmonella spp. | Salmonella spp. |

| Treponema pallidum (TP) | Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) | Giardia lamblia spp. |

| Herpes simplex virus (HSV) | CT-LGV-L1-L3 | Cryptosporidium spp.a,c |

| Mycoplasma genitalium (MG)a | Clostridioides difficileb | Isospora bellia,c |

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV)a,c | Cryptosporidium spp. | Microsporidium spp.a,c |

| Mpox | Human intestinal spirochetosis (HIS)d | Strongyloides stercoralisb |

| Entamoeba histolytica | Entamoeba histolytica | |

| CMVa,c | Mycobacterium avium-intracellularea,c | |

| CMVa,c |

The approach to cases can be divided into several parts: identification of the cause, treatment of the cause, follow-up, and test of cure.

Identification of the causeTo identify the cause, it is necessary to conduct a clinical history, a physical examination, and a few additional tests.

Clinical historyIt is recommended to establish the specific etiology to prevent complications, reinfections, and transmissions, as a specific diagnosis could improve treatment compliance, risk reduction interventions, and proper contact tracing.25

In the clinical history, we should inquire about previous STIs, the time since symptom onset, sexual behavior, the last sexual contact, number of partners over the past 1, 3, and 6 months; condom use during vaginal, anal, or oral sex; use of substances, toxins, or toys in a sexual context; patient's travel history and profession (e.g., food handlers or sex workers),26,27 and previous drugs for these symptoms (level of evidence 4, grade of recommendation C).

Physical examinationIn the physical examination for urethritis, we should consider the color, amount, and consistency of the discharge. We should also check for signs of meatitis, balanoposthitis, epididymo-orchitis, or inguinal lymphadenopathy. Depending on the type of sexual activity, we should examine the anorectal mucosa, the oral cavity, and look for other systemic symptoms such as conjunctivitis or reactive arthritis. The presence of conjunctivitis-related meatitis could point toward a viral cause.28

In suspected proctitis/proctocolitis, it is advisable to palpate the abdomen to check for signs of peritonitis, inspect the perianal region, and perform a conventional anoscopy/proctoscopy if possible.

Table 3 illustrates the differential diagnosis of urethritis, and Table 4 the differential diagnosis of proctitis, proctocolitis, and enteritis.

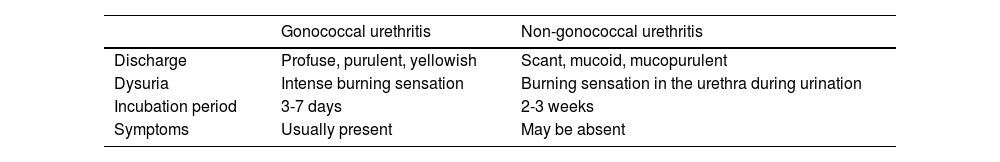

Differential diagnosis of gonococcal and non-gonococcal urethritis.13

| Gonococcal urethritis | Non-gonococcal urethritis | |

|---|---|---|

| Discharge | Profuse, purulent, yellowish | Scant, mucoid, mucopurulent |

| Dysuria | Intense burning sensation | Burning sensation in the urethra during urination |

| Incubation period | 3-7 days | 2-3 weeks |

| Symptoms | Usually present | May be absent |

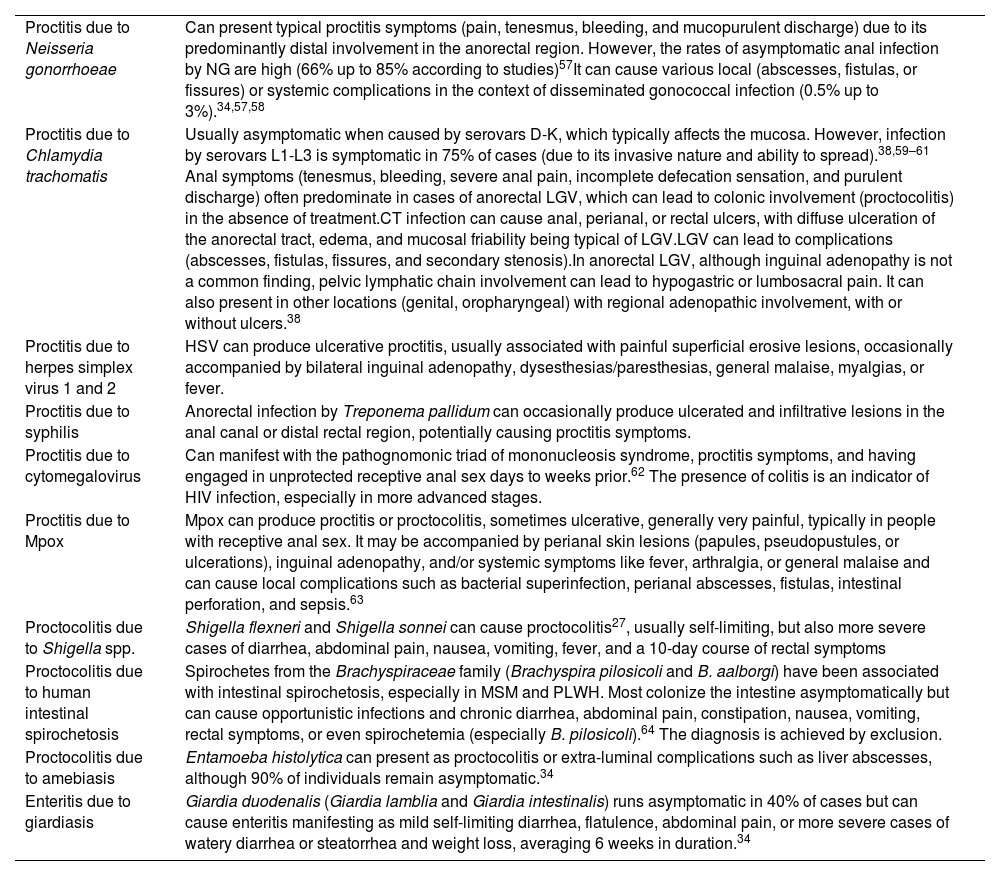

Differential diagnosis of proctitis, proctolitis, and enteritis.

| Proctitis due to Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Can present typical proctitis symptoms (pain, tenesmus, bleeding, and mucopurulent discharge) due to its predominantly distal involvement in the anorectal region. However, the rates of asymptomatic anal infection by NG are high (66% up to 85% according to studies)57It can cause various local (abscesses, fistulas, or fissures) or systemic complications in the context of disseminated gonococcal infection (0.5% up to 3%).34,57,58 |

| Proctitis due to Chlamydia trachomatis | Usually asymptomatic when caused by serovars D-K, which typically affects the mucosa. However, infection by serovars L1-L3 is symptomatic in 75% of cases (due to its invasive nature and ability to spread).38,59–61 Anal symptoms (tenesmus, bleeding, severe anal pain, incomplete defecation sensation, and purulent discharge) often predominate in cases of anorectal LGV, which can lead to colonic involvement (proctocolitis) in the absence of treatment.CT infection can cause anal, perianal, or rectal ulcers, with diffuse ulceration of the anorectal tract, edema, and mucosal friability being typical of LGV.LGV can lead to complications (abscesses, fistulas, fissures, and secondary stenosis).In anorectal LGV, although inguinal adenopathy is not a common finding, pelvic lymphatic chain involvement can lead to hypogastric or lumbosacral pain. It can also present in other locations (genital, oropharyngeal) with regional adenopathic involvement, with or without ulcers.38 |

| Proctitis due to herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 | HSV can produce ulcerative proctitis, usually associated with painful superficial erosive lesions, occasionally accompanied by bilateral inguinal adenopathy, dysesthesias/paresthesias, general malaise, myalgias, or fever. |

| Proctitis due to syphilis | Anorectal infection by Treponema pallidum can occasionally produce ulcerated and infiltrative lesions in the anal canal or distal rectal region, potentially causing proctitis symptoms. |

| Proctitis due to cytomegalovirus | Can manifest with the pathognomonic triad of mononucleosis syndrome, proctitis symptoms, and having engaged in unprotected receptive anal sex days to weeks prior.62 The presence of colitis is an indicator of HIV infection, especially in more advanced stages. |

| Proctitis due to Mpox | Mpox can produce proctitis or proctocolitis, sometimes ulcerative, generally very painful, typically in people with receptive anal sex. It may be accompanied by perianal skin lesions (papules, pseudopustules, or ulcerations), inguinal adenopathy, and/or systemic symptoms like fever, arthralgia, or general malaise and can cause local complications such as bacterial superinfection, perianal abscesses, fistulas, intestinal perforation, and sepsis.63 |

| Proctocolitis due to Shigella spp. | Shigella flexneri and Shigella sonnei can cause proctocolitis27, usually self-limiting, but also more severe cases of diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, and a 10-day course of rectal symptoms |

| Proctocolitis due to human intestinal spirochetosis | Spirochetes from the Brachyspiraceae family (Brachyspira pilosicoli and B. aalborgi) have been associated with intestinal spirochetosis, especially in MSM and PLWH. Most colonize the intestine asymptomatically but can cause opportunistic infections and chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, constipation, nausea, vomiting, rectal symptoms, or even spirochetemia (especially B. pilosicoli).64 The diagnosis is achieved by exclusion. |

| Proctocolitis due to amebiasis | Entamoeba histolytica can present as proctocolitis or extra-luminal complications such as liver abscesses, although 90% of individuals remain asymptomatic.34 |

| Enteritis due to giardiasis | Giardia duodenalis (Giardia lamblia and Giardia intestinalis) runs asymptomatic in 40% of cases but can cause enteritis manifesting as mild self-limiting diarrhea, flatulence, abdominal pain, or more severe cases of watery diarrhea or steatorrhea and weight loss, averaging 6 weeks in duration.34 |

CT: Chlamydia trachomatis; HSH: men who have sex with men; LGV: lymphogranuloma venereum; HSV: herpes simplex virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

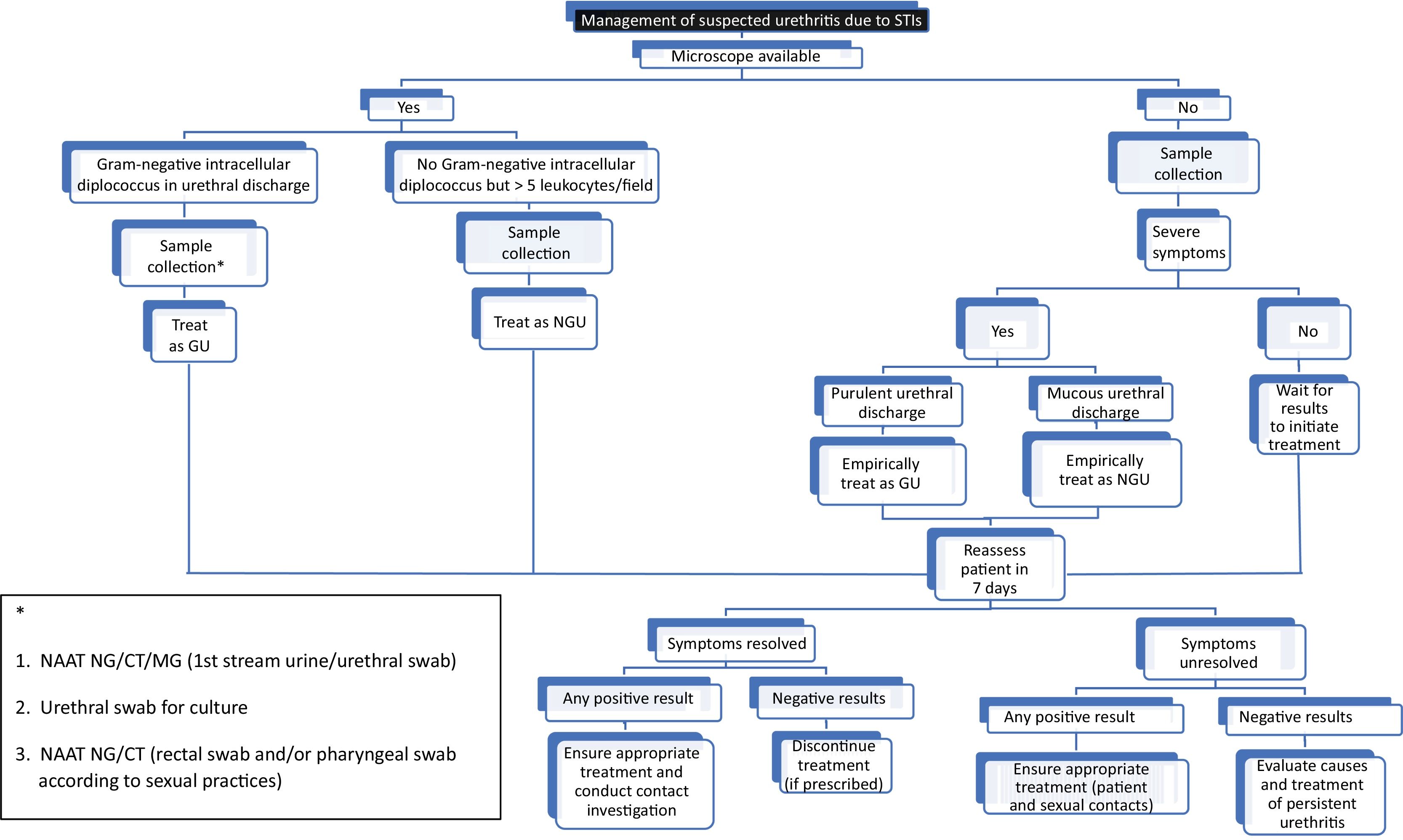

For symptomatic patients and those with visible discharge, experts recommend confirming urethritis in the clinic as a guide for immediate treatment, without waiting for the lab test results (Fig. 1) (level of evidence 2a, grade of recommendation C). Urethritis is confirmed if a urethral sample—stained with methylene blue or Gram stain—contains, at least, 5 polymorphonuclear leukocytes per high-power field.2,13 However, this study is often unavailable in most centers, is not recommended to rule out asymptomatic urethritis—contact tracing or screening—may cause inter/intra-observer differences, and its sensitivity depends on how the sample is obtained.

What tests should we perform?

- 1.

Nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) to detect NG and CT in the first void urine or urethral sample (level of evidence 1b, grade of recommendation A).29 Both samples have the same sensitivity if taken correctly. It is also strongly recommended to test for MG, preferably with macrolide resistance detection.

- •

The first void urine should not contain more than 10mL, as a larger volume will reduce sensitivity, and the post-urination interval should extend for, at least, 2hours.

- •

If a urethral sample is taken instead2: retract the foreskin, clean the meatus with saline, and gently insert the swab into the urethra to collect the sample. If urethral discharge is present, it can be collected without inserting the swab into the meatus (level of evidence 4, grade of recommendation C).

- •

- 2.

Another urethral or discharge sample for bacterial culture to perform an antibiogram if necessary. This sample can be self-collected by the patient (level of evidence 4, grade of recommendation C).30

- 3.

Additionally, NAAT is recommended to detect NG and CT at any potentially exposed site depending on sexual activity (rectal and/or pharyngeal swabs). With appropriate instructions, self-collection of rectal and/or pharyngeal swabs by the patient for NG and CT detection has proven to be a valid and acceptable option (level of evidence 2a, grade of recommendation B).31,32

What tests should we avoid?

Routine testing or treatment of asymptomatic or symptomatic men for M. hominis, U. urealyticum, and U. parvum is ill-advised.2 Asymptomatic colonization by these bacteria is common, and most individuals do not develop disease. Although U. urealyticum has been associated with urethritis in men, most infected/colonized men do not develop disease. Therefore, other causes (NG, CT, MG, and TV in men who have sex with women) should be excluded before testing for U. urealyticum in symptomatic men. Lastly, it is advised to treat only men with a high bacterial load (> 1000 copies/mL of U. urealyticum in first void urine).2

In patients with symptoms of cervicitisWhat tests should we perform?

Since cervicitis can be a sign of upper genital tract infection (e.g., endometritis), women should be evaluated for signs of pelvic inflammatory disease and tested for CT and NG using NAAT on vaginal, cervical, or urine samples13 (level of evidence 2a, grade of recommendation B). Vaginal sampling can be performed by the physician or through self-collection. Women with cervicitis should also be evaluated for bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis. Since the sensitivity of microscopy for detecting T. vaginalis is relatively low (approximately 50%), symptomatic women with cervicitis and negative microscopy for trichomonas should undergo further testing (mainly NAAT). Testing for MG using NAAT should also be considered. Although HSV infection has been associated with cervicitis, testing should only be performed if the patient presents with symptoms compatible with genital herpes.

Additionally, it is important for patients to undergo testing for CT and NG at any potentially exposed site based on the type of sexual activity (rectal and/or pharyngeal swabs) (level of evidence 2b, grade of recommendation B).

What tests should we avoid?

Testing for U. parvum, U. urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, or genital culture for group B streptococcus is ill-advised.

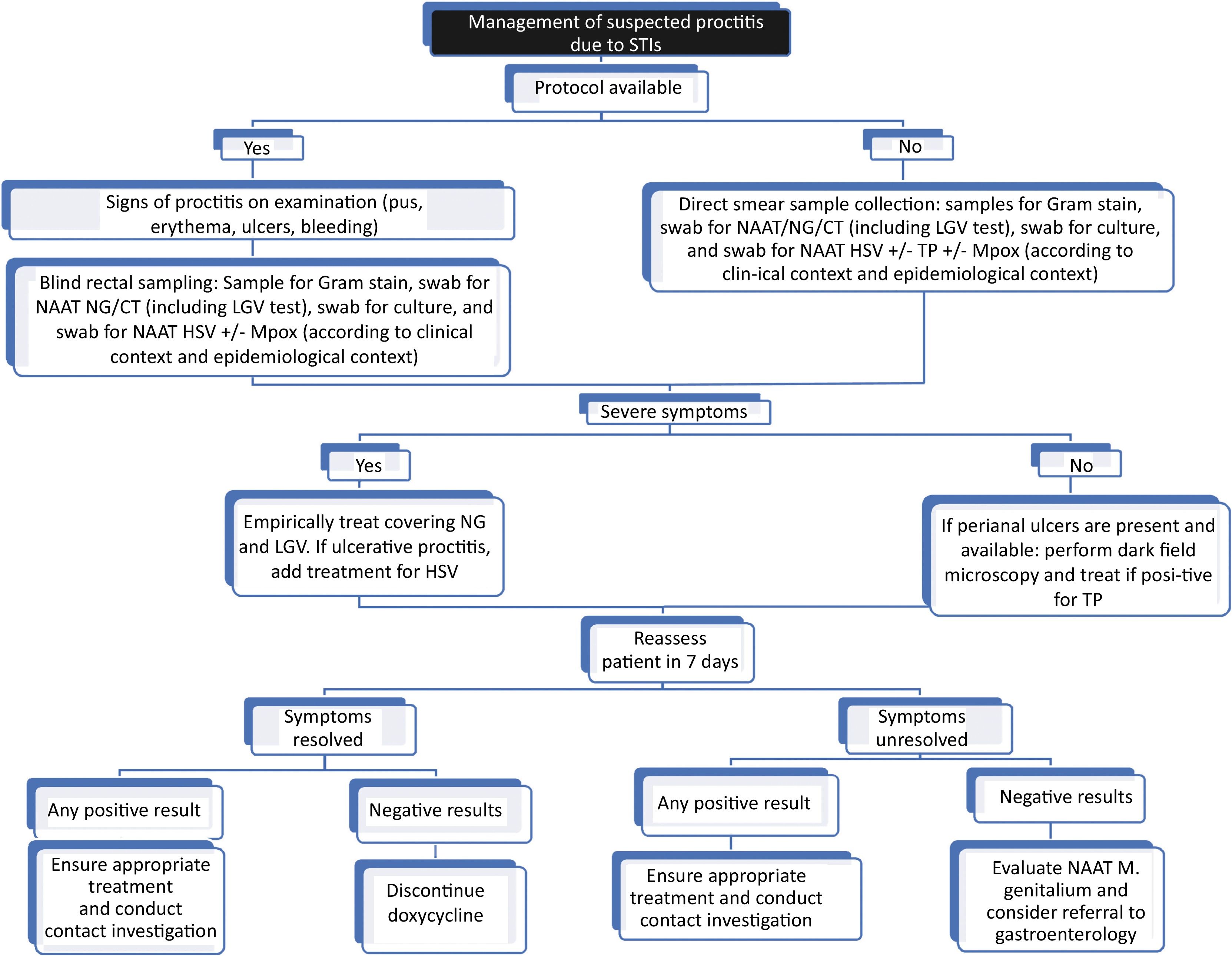

In patients with symptoms of proctitisSamples should be collected to confirm the suspected microbiological diagnosis (by inserting a swab through the anal canal or visualizing through anoscopy/proctoscopy) (Fig. 2):

- 1.

Gram stain of rectal secretions (if available).

- 2.

Culture of rectal secretions to perform an antibiogram if necessary (level of evidence 3a, grade of recommendation C).33,34

- 3.

NAAT of rectal secretions to detect NG and CT (serovars D-K and L1-L3) (level of evidence 2a, grade of recommendation B).35 Althought this is the test of choice, the study can be expanded to other pathogens such as T. pallidum (TP),36 HSV,37 and/or Mpox, in the presence of clinical suspicion. Any positive rectal NAAT for CT should be typed to rule out lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) (level of evidence 2a, grade of recommendation B).38 Initially, specific NAAT for MG is not recommended, but if positive and available, a macrolide resistance test is suggested (level of evidence 3b, grade of recommendation C).39

- 4.

In the presence of ulcerated lesions in the rectum or perianal area, an exudate sample can be taken for dark-field microscopy and TP and/or HSV detection by NAAT.

- 5.

In cases of suspected cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, useful tests include CMV IgM/IgG serology, NAAT, and immunohistochemistry of biopsies.40

Self-collection of a rectal swab for dual NAAT for CT and NG in high-risk asymptomatic patients (e.g., those taking pre-exposure prophylaxis [PEP], people living with HIV [PLWH] with multiple partners, MSM engaging in unprotected receptive anal sex in the last 6 months) is a valid option (level of evidence 2a, grade of recommendation B).41

In patients with symptoms of proctocolitis or enteritisIn patients with symptoms of proctocolitis or enteritis, especially if they present with a > 7-day history of diarrhea and fever, it is recommended to assess stool culture, NAAT for bacteria and parasites in stool, rectosigmoidoscopy or upper and lower GI endoscopy, among other additional tests depending on clinical presentation and availability.

CT-LGV proctitis can clinically and even histopathologically mimic other proctocolitis syndromes; therefore, it should be considered in MSM with suspected chronic inflammatory bowel disease (level of evidence 4, grade of recommendation C).42

TreatmentEmpirical treatment of urethritisAs empirical treatment, if intracellular diplococci have been identified under the microscope, or the patient has purulent urethral discharge, after collecting samples for analysis, the case is treated as gonococcal urethritis, and treatment is recommended.43 All experts and current clinical practice guidelines agree that ceftriaxone should be the first-line therapy, although they differ on the recommended dose. The CDC (US Department of Health and Human Services/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)44 guidelines recommend 500mg IM/single dose (except if weight ≥ 150kg where 1g IM/single dose is recommended), while the BASHH (British Association of Sexual Health and HIV Clinical Effectiveness Group)45 guidelines recommend 1g IM/single dose, and the International Union Against Sexually Transmitted Infection (IUSTI)43 guidelines recommend 1g IM single dose combined with azithromycin 2g orally/single dose.

According to the British guidelines, the ceftriaxone dose was up titrated from 500mg up to 1g because ceftriaxone-resistant strains have been identified worldwide—most linked to the Asia-Pacific region—although a 500mg ceftriaxone dose would be sufficient to treat most gonococcal strains in Europe.45

Similarly, the British guidelines45 no longer recommend dual therapy with 1g azithromycin. Evidence suggesting a synergy between cephalosporins and azithromycin in vitro is inconclusive. The prevalence of azithromycin resistance has increased, and although some ceftriaxone-resistant strains are sensitive to azithromycin, a 1g azithromycin dose may be insufficient to eradicate the infection, and a 2g dose increases the incidence of GI side effects.45

Additionally, co-infection with CT is a common finding in young heterosexual patients (younger than 30 years) and MSM with GU. In these cases, the IUSTI guidelines43 recommend adding doxycycline 100mg orally, twice a day for 7 days to ceftriaxone IM treatment if dual therapy with azithromycin has not been prescribed, until possible chlamydia co-infection is excluded. In contrast, the CDC guidelines44 recommend adding doxycycline in all cases until CT infection is excluded.

In conclusion, in case of potential gonococcal urethritis, empirical treatment is advised with:

- •

Ceftriaxone 500mg or 1g IM/single dose (level of evidence 1b, grade of recommendation A) + doxycycline 100mg orally, twice a day for 7 days (level of evidence 2b, grade of recommendation C).

For patients with urethritis symptoms but without gram-negative diplococci detected in the exudate on microscopic examination, or if they exhibit mucous discharge, the case should be treated as NGU until the sample results are available.2,46 In men with mild symptoms and urethritis not confirmed microscopically, treatment is not recommended until sample results—which usually take 3 to 7 days—are obtained and should guide antimicrobial therapy.

Patients with severe symptoms should receive treatment after sample collection for analysis without having to wait for the microbiological test results. In these cases, the recommended empirical treatment is:

- •

Doxycycline 100mg orally, twice a day for 7 days (level of evidence 1b, grade of recommendation A).

Azithromycin 1g should not be routinely used due to the risk of inducing macrolide resistance in MG.13,46

Empirical treatment of cervicitisEmpirical treatment for cervicitis should include antibiotics that cover CT:

- •

Doxycycline 100mg orally, twice a day for 7 days (level of evidence 1b, grade of recommendation A).

Treatment to cover NG should be added in women at higher risk (e.g., age < 25 years, new sexual partner, a sexual partner with concurrent partners, having an STI or risk of gonorrhea, or living in a community with high gonorrhea prevalence).13 Trichomoniasis and bacterial vaginosis (BV) should only be treated if detected.

For women at low risk of STIs, treatment may be postponed until diagnostic test results are available.

Empirical treatment of proctitisIn cases of suspected acute proctitis with clinical symptoms, empirical treatment should begin without having to wait for the test results (level of evidence 2a, grade of recommendation B).34

- •

Ceftriaxone 500mg or 1g IM/single dose + doxycycline 100mg orally, twice a day for 7 days (extended to 21 days in the case of LGV) (level of evidence 3a, grade of recommendation B).34,37

- •

In cases of painful ulcerative proctitis suggestive of herpes simplex, especially in MSM and PLWH, add treatment for herpes simplex (level of evidence 4, grade of recommendation C).

Initially, supportive measures and rehydration are necessary, and empirical antibiotic treatment is generally not required (level of evidence 1b, grade of recommendation B).47 Empirical treatment may be considered based on local epidemiology if associated with severe symptoms, sepsis, or need for hospitalization (due to severe dehydration, intractable vomiting, severe diarrhea, acute renal failure, or comorbidities).

Result-guided treatmentOnce microbiological results are available, appropriate treatment should be adjusted. Table 5 illustrates the specific treatment in each case. Information that is expanded in Annex 1 of the supplementary data. The treatment of special cases—PLWH, pregnant women, or those allergic to antibiotics—is shown in Annex 2 of the supplementary data.

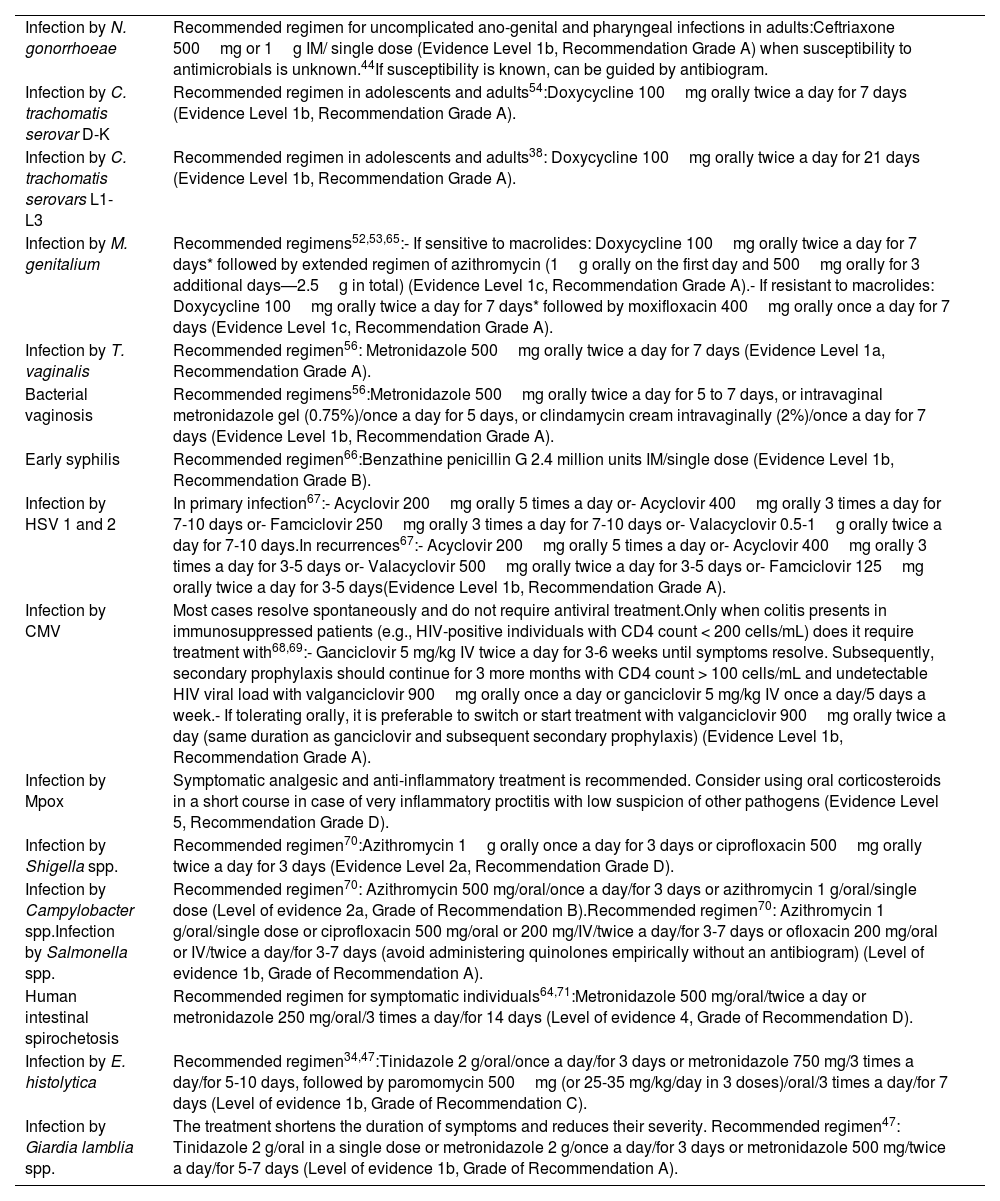

Specific treatment for cases.

| Infection by N. gonorrhoeae | Recommended regimen for uncomplicated ano-genital and pharyngeal infections in adults:Ceftriaxone 500mg or 1g IM/ single dose (Evidence Level 1b, Recommendation Grade A) when susceptibility to antimicrobials is unknown.44If susceptibility is known, can be guided by antibiogram. |

| Infection by C. trachomatis serovar D-K | Recommended regimen in adolescents and adults54:Doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day for 7 days (Evidence Level 1b, Recommendation Grade A). |

| Infection by C. trachomatis serovars L1-L3 | Recommended regimen in adolescents and adults38: Doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day for 21 days (Evidence Level 1b, Recommendation Grade A). |

| Infection by M. genitalium | Recommended regimens52,53,65:- If sensitive to macrolides: Doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day for 7 days* followed by extended regimen of azithromycin (1g orally on the first day and 500mg orally for 3 additional days—2.5g in total) (Evidence Level 1c, Recommendation Grade A).- If resistant to macrolides: Doxycycline 100mg orally twice a day for 7 days* followed by moxifloxacin 400mg orally once a day for 7 days (Evidence Level 1c, Recommendation Grade A). |

| Infection by T. vaginalis | Recommended regimen56: Metronidazole 500mg orally twice a day for 7 days (Evidence Level 1a, Recommendation Grade A). |

| Bacterial vaginosis | Recommended regimens56:Metronidazole 500mg orally twice a day for 5 to 7 days, or intravaginal metronidazole gel (0.75%)/once a day for 5 days, or clindamycin cream intravaginally (2%)/once a day for 7 days (Evidence Level 1b, Recommendation Grade A). |

| Early syphilis | Recommended regimen66:Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM/single dose (Evidence Level 1b, Recommendation Grade B). |

| Infection by HSV 1 and 2 | In primary infection67:- Acyclovir 200mg orally 5 times a day or- Acyclovir 400mg orally 3 times a day for 7-10 days or- Famciclovir 250mg orally 3 times a day for 7-10 days or- Valacyclovir 0.5-1g orally twice a day for 7-10 days.In recurrences67:- Acyclovir 200mg orally 5 times a day or- Acyclovir 400mg orally 3 times a day for 3-5 days or- Valacyclovir 500mg orally twice a day for 3-5 days or- Famciclovir 125mg orally twice a day for 3-5 days(Evidence Level 1b, Recommendation Grade A). |

| Infection by CMV | Most cases resolve spontaneously and do not require antiviral treatment.Only when colitis presents in immunosuppressed patients (e.g., HIV-positive individuals with CD4 count < 200 cells/mL) does it require treatment with68,69:- Ganciclovir 5 mg/kg IV twice a day for 3-6 weeks until symptoms resolve. Subsequently, secondary prophylaxis should continue for 3 more months with CD4 count > 100 cells/mL and undetectable HIV viral load with valganciclovir 900mg orally once a day or ganciclovir 5 mg/kg IV once a day/5 days a week.- If tolerating orally, it is preferable to switch or start treatment with valganciclovir 900mg orally twice a day (same duration as ganciclovir and subsequent secondary prophylaxis) (Evidence Level 1b, Recommendation Grade A). |

| Infection by Mpox | Symptomatic analgesic and anti-inflammatory treatment is recommended. Consider using oral corticosteroids in a short course in case of very inflammatory proctitis with low suspicion of other pathogens (Evidence Level 5, Recommendation Grade D). |

| Infection by Shigella spp. | Recommended regimen70:Azithromycin 1g orally once a day for 3 days or ciprofloxacin 500mg orally twice a day for 3 days (Evidence Level 2a, Recommendation Grade D). |

| Infection by Campylobacter spp.Infection by Salmonella spp. | Recommended regimen70: Azithromycin 500 mg/oral/once a day/for 3 days or azithromycin 1 g/oral/single dose (Level of evidence 2a, Grade of Recommendation B).Recommended regimen70: Azithromycin 1 g/oral/single dose or ciprofloxacin 500 mg/oral or 200 mg/IV/twice a day/for 3-7 days or ofloxacin 200 mg/oral or IV/twice a day/for 3-7 days (avoid administering quinolones empirically without an antibiogram) (Level of evidence 1b, Grade of Recommendation A). |

| Human intestinal spirochetosis | Recommended regimen for symptomatic individuals64,71:Metronidazole 500 mg/oral/twice a day or metronidazole 250 mg/oral/3 times a day/for 14 days (Level of evidence 4, Grade of Recommendation D). |

| Infection by E. histolytica | Recommended regimen34,47:Tinidazole 2 g/oral/once a day/for 3 days or metronidazole 750 mg/3 times a day/for 5-10 days, followed by paromomycin 500mg (or 25-35 mg/kg/day in 3 doses)/oral/3 times a day/for 7 days (Level of evidence 1b, Grade of Recommendation C). |

| Infection by Giardia lamblia spp. | The treatment shortens the duration of symptoms and reduces their severity. Recommended regimen47: Tinidazole 2 g/oral in a single dose or metronidazole 2 g/once a day/for 3 days or metronidazole 500 mg/twice a day/for 5-7 days (Level of evidence 1b, Grade of Recommendation A). |

IM: intramuscular route; IV: intravenous route.

We should always explain the causes of the infection, potential short- and long-term consequences, side effects of treatment, and the importance of evaluating and treating sexual partner(s), as well as follow-up.34,46

To minimize transmission and reinfection, patients should be advised to abstain from sexual activity, including oral sex, until they and their partner(s) have been treated (i.e., 7 days after single-dose treatment or until completing a therapeutic regimen and symptoms have resolved).44

Patients should be advised to screen for other STIs (HIV, syphilis, others based on sexual history), recommended for vaccination (if no prior immunity) for hepatitis A and B, HPV, and Mpox; and offered advice on starting PEP (based on sexual history).48 (level of evidence 4, grade of recommendation D).

Finally, infections caused by Campylobacter spp., CT D-K, CT LGV-L1-3, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, Giardia lamblia spp., Mpox, NG, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., and TP are reportable.49

Contact tracingAll at-risk sexual partners should be assessed and offered epidemiological treatment, maintaining patient confidentiality.50

The time frame considered for evaluating sexual partners is arbitrary (see suggested times in the manuscript “Expert recommendations of the AEDV on legal aspects in the management of sexually transmitted infections”).51

Follow-upFollow-up is recommended to confirm:

- •

Completion of therapy

- •

Resolution of symptoms and signs

- •

Exclusion of reinfection

- •

Notification of partner(s)

In the case of shigellosis in food handlers or health care personnel, there may be regulations on when to return to work after symptoms disappear.34

Annex 3 of the supplementary data outlines the management of patients with persistent urethritis or cervicitis symptoms.

Test of cure (TOC)Gonococcal infection43,44All patients diagnosed with gonorrhea should be recommended to return for TOC, especially in the presence of:

- 1.

Persistent symptoms or signs

- 2.

Pharyngeal infection

- 3.

Treated with any regimen other than first-line therapy, or

- 4.

The infection was acquired in the Asia-Pacific region

If symptoms persist, a culture should be performed 3 to 7 days after treatment. For all other cases, a sample for NAAT should be taken 2 weeks after treatment. If NAAT tests positive, an effort should be made for culture confirmation before retreatment. All positive cultures from TOC should undergo antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Non-gonococcal urethritis/cervicitis/proctitisM. genitalium32,52: TOC should be considered for all patients due to the high prevalence of resistance, especially in the presence of:

- 1.

Persistent urethritis, or

- 2.

Cervicitis, or

- 3.

PID, or

- 4.

A regimen including azithromycin was used without a macrolide resistance test

TOC samples should be collected 4-5 weeks (and not earlier than 3 weeks to avoid false negatives) after the start of treatment to ensure microbiological cure and help identify emerging resistance.

C. trachomatis53–55: Routine TOC is not recommended in patients treated with the recommended first-line regimens but should be performed in the presence of:

- 1.

Pregnancy

- 2.

Complicated infections

- 3.

Persistent symptoms

- 4.

Second or third-line regimens were used

- 5.

Treatment noncompliance, or

- 6.

Detection of rectal CT but no LGV test has been conducted

TOC should be postponed for, at least, 3 weeks after therapy ends because NAAT can detect residual non-viable chlamydia DNA for 3 to 5 weeks after treatment.

T. vaginalis and bacterial vaginosis56: TOC is only recommended in women with persistent symptoms or during pregnancy, 4 to 5 weeks after treatment.

AddendumThis article used the levels of evidence from the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (CEBM).72–74Annex 4d of the supplementary data explains how these levels of evidence are classified.

Conflicts of interestNone declared