Vitiligo affects nearly 2% of the world's population.1 The extent of vitiligo is measured as a percentage of affected body surface area (BSA) and is calculated using the Vitiligo Extent Score (VES), a validated scale frequently used for this purpose.2,3

Clinical signs predictive of “fast progression” have been described,4,5 but currently, there is no quantitative or standardized method to measure the speed of progression.

The concept of “progression rate” (PR) is proposed as an index to measure the speed of non-segmental vitiligo (NSV) progression as a reference.

Patients and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted at Dr. Ladislao de la Pascua Dermatology Center in Mexico City, Mexico. Patients aged 18 and older diagnosed with NSV by a dermatologist were included after giving their prior written informed consent. BSA was measured using the VES, and PR was calculated by dividing the percentage of total BSA by the years lived with vitiligo: PR=%BSA/(years with vitiligo); adjusted PR: PR=%BSA/(years with vitiligo-period without progression).

Patients were asked: “Since you developed vitiligo until now, have you ever had any period of time when the white spots did not increase in size, or new ones did not appear?” They were asked to recall the approximate timeframe, and if there were multiple periods, to quantify the total timeframe.

The research and ethics committee approved the research protocol.

ResultsA total of 492 patients participated in the study, with a mean age of 45.5±15 years (86% of the patients had Fitzpatrick skin types III and IV).

The speed of progression was categorized as “slow,” “moderate,” and “fast” (table 1).

Comparison of clinical characteristics of patients with non-segmental vitiligo based on the speed of progression (n=492).

| Slow(<0.04%)n=119 | Moderate(0.04% to 0.58%)n=250 | Fast(>0.58%)n=123 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 45±15 (18-77) | 45±15 (18-80) | 47±15 (18-81) | .50* |

| Women | 79 (66.4%) | 153 (61.2%) | 76 (61.8%) | .48** |

| AO | 34 (14-45) (3-72) | 36 (21-48) (1-77) | 38 (27-54) (6-80) | .003*** |

| Course of the disease | 11 y (6 to 19 y) (1 to 52 y) | 5 y (2 to 12 y) (1 m to 69 y) | 2 y (1 to 10 y) (1 m to 64 y) | <.001*** |

| BSA% | 0.12 (0.06-0.26) (0.01-0.91) | 0.71 (0.25-2.1) (0.01-21.5) | 4.1 (1.2-14.4) (0.09-74.7) | <.001*** |

| PR%annual | 0.01 (0.008-0.02) (0-0.04) | 0.15 (0.08-0.29) (0.04-0.5) | 1.1 (0.76-2.8) (0.53-74.0) | <.001**** |

Mean±standard deviation; median (percentile 25-75) range. Speed of progression categorized as (slow) annual PR < 25th percentile, moderate from the 25th to the 75th percentile, and fast > 75th percentile.

AO, age of onset; BSA, body surface area; m, months; PR, progression rate; y, years.

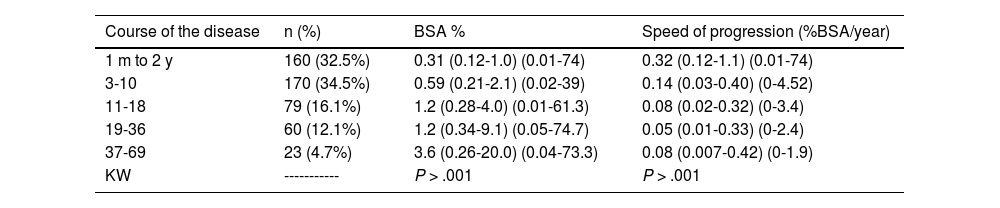

Table 2 and of the supplementary data show BSA and PR stratified by disease duration and age. A total of 16% of the patients reported periods without progression. The adjusted PR was calculated by deducting that time (table 3).

Body surface area and speed of progression stratified by the course of the disease (n=492).

| Course of the disease | n (%) | BSA % | Speed of progression (%BSA/year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 m to 2 y | 160 (32.5%) | 0.31 (0.12-1.0) (0.01-74) | 0.32 (0.12-1.1) (0.01-74) |

| 3-10 | 170 (34.5%) | 0.59 (0.21-2.1) (0.02-39) | 0.14 (0.03-0.40) (0-4.52) |

| 11-18 | 79 (16.1%) | 1.2 (0.28-4.0) (0.01-61.3) | 0.08 (0.02-0.32) (0-3.4) |

| 19-36 | 60 (12.1%) | 1.2 (0.34-9.1) (0.05-74.7) | 0.05 (0.01-0.33) (0-2.4) |

| 37-69 | 23 (4.7%) | 3.6 (0.26-20.0) (0.04-73.3) | 0.08 (0.007-0.42) (0-1.9) |

| KW | ----------- | P > .001 | P > .001 |

Median (percentile 25-75); KW (Kruskal-Wallis)

m, months; y, years.

Comparison of the speed of progression in patients with and without an increase in lesion size and/or number of lesions reported.

| n (%) | Speed of progression p50 (p25-75) | (%BSA/year)Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 492 (100) | 0.16 (0.04-0.53) | 0-74 |

| Persistent progression | 412 (83.7) | 0.17 (0.05-0.57) | 0-74 |

| With periods without progression | 79 (16.1) | 0.10 (0.03-0.35) | 0-6 |

| Adjusted PRa | 489 (99.4) | 0.17 (0.04-0.58) | 0-74 |

Speed of progression: percentage of body surface area affected per year (%BSA/year). Percentile p50 (p25-75).

Correlations among age, age of onset, disease duration, BSA, and PR were statistically significant (P<.05) (table 2, and Figure 1 of the supplementary data). The correlation between the course of the disease and BSA was 0.32 (P<.001), and between the course of the disease and PR, -0.30 (P<.001) (Figures 2 and 3 of the supplementary data).

DiscussionUnderstanding the clinical course of the disease allows us to establish prognosis. The progression of NSV is defined as unpredictable;4 generally, the skin is affected slowly but progressively throughout life, although some patients may experience fast progressions, remain unchanged for years, and “few” reach universal vitiligo. To this date, it is still unknown whether treatment response changes with the course of the disease or the accumulated damage, or if treatment reduces the long-term speed of progression.

PR can be a tool to collect data to answer these questions.6,7 In the studied patients, 24%, 51%, and 25% showed slow, moderate, and fast progressions, respectively (table 1).

In time, accumulated damage increases, yet speed of progression slows down (table 2). This may explain the low prevalence of universal vitiligo.

Based on the data obtained, we can assume that in 50% of the patients—similar rate to that of our sample—progression would be <0.2%/year, while in 90% of the patients, the increase would not exceed 2%/year. Regarding cumulative damage, 50% of the patients would have <0.6% of BSA affected, while in 90% of the patients, cumulative damage would not affect >9% of BSA, which explains the low prevalence of universal vitiligo, somewhere around 0.39% and 6.2% (Figure 2 of the supplementary data).8,9

Patient-provided data are subjective; however, according to Férez-Blando, patients do not forget when the disease started, or the course of the disease.10 The impact of the small number of patients with periods without progression on PR calculation was limited (table 3).

The course of the disease explains 10% of BSA variation, and 9% of speed of progression (table 2 and Figure 3 of the supplementary data).

The size and direction of correlations among different variables were observed, with only the relationship between patient age and the speed of progression lacking statistical significance (table 2 and Figure 1 of the supplementary data).

The speed of progression likely reflects the aggressiveness of the autoimmune response. Age and gender do not impact PR, and an older age of onset may be associated with a higher PR, while a longer course of the disease may decrease the speed of progression, or else, the disease may have a faster progression at the beginning regardless of age. More studies on prognostic factors are needed to confirm these findings.

The study has some limitations such as its cross-sectional design. Still, it is a good alternative to the challenge of conducting large prospective longitudinal studies, which would be the ideal scenario here. Also, although PR quantifies the rate of progression uniformly over time it should be considered only as an overall estimate at the time of evaluation.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

We would like to express our gratitude to the Medicine for Education, Development, and Scientific Research Program of Iztacala-MEDICI, from Escuela de Estudios Superiores Iztacala UNAM, for considering the Research Unit of the Dr. Ladislao de la Pascua Dermatology Center as a venue for their research-based social service.