The epidemiological surveillance of contact dermatitis is one of the objectives of the Spanish Registry of Research in Contact Dermatitis and Cutaneous Allergy. Knowing whether the prevalence of positive tests to the different allergens changes over time is important for this monitoring process.

ObjectivesTo describe the various temporary trends in allergen positivity in the GEIDAC standard series from 2018 through December 31, 2022.

MethodsThis was a multicenter, observational trial of consecutive patients analyzed via patch tests as part of the study of possible allergic contact dermatitises collected prospectively within the Spanish Registry of Research in Contact Dermatitis and Cutaneous Allergy. The data was analyzed using 2 statistical tests: one homogeneity test (to describe the changes seen over time) and one trend test (to see whether the changes described followed a linear trend).

ResultsA total of 11327 patients were included in the study. Overall, the allergens associated with a highest sensitization were nickel sulfate, methylisothiazolinone, cobalt chloride, methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone, and fragrance mix i. A statistically significant decrease was found in the percentage of methylisothiazolinone positive tests across the study years with an orderly trend.

ConclusionsAlthough various changes were seen in the sensitizations trends to several allergens of the standard testing, it became obvious that a high sensitization to nickel, methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone and fragrances mix i remained. Only a significant downward trend was seen for methylisothiazolinone.

El Registro Español de Investigación en Dermatitis de Contacto y Alergia Cutánea tiene entre sus objetivos la vigilancia epidemiológica de la dermatitis de contacto. Para ello es importante conocer si se producen alteraciones en el tiempo de las prevalencias de las positividades a los distintos alérgenos.

ObjetivosDescribir las variaciones en las tendencias temporales en positividades a alérgenos en la serie estándar del GEIDAC en el periodo comprendido entre 2018 y el 31 de diciembre de 2022.

MétodosEstudio observacional multicéntrico de pacientes estudiados consecutivamente mediante pruebas epicutáneas dentro del estudio de un posible eczema alérgico de contacto recogidos de forma prospectiva en el seno del Registro Español de Investigación en Dermatitis de Contacto y Alergia Cutánea. Se analizaron los datos mediante 2 pruebas estadísticas: una de homogeneidad (para ver si hay cambios en los diferentes años) y otra de tendencia (para ver si los cambios siguen una tendencia lineal).

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 11.327 pacientes en el periodo de estudio. Los alérgenos en los que de forma global se detectó una sensibilización mayor fueron sulfato de níquel, metilisotiazolinona, cloruro de cobalto, metilcloroisotiazolinona/metilisotiazolinona y mezcla de fragancias i. Se detectó una disminución estadísticamente significativa en el porcentaje de positividades de metilisotiazolinona a lo largo de años de estudio con una tendencia ordenada.

ConclusionesSi bien se pueden apreciar diferentes cambios en las tendencias a sensibilizaciones a varios de los alérgenos de la batería estándar, se observa que persiste una alta sensibilización al níquel, a la metilcloroisotiazolinona/metilisotiazolinona y a la mezcla de fragancias i. Solo se aprecia una tendencia a disminuir de forma significativa en el caso de la metilisotiazolinona.

The Spanish Registry of Research in Contact Dermatitis and Cutaneous Allergy (REIDAC) has, among its objectives, the epidemiological surveillance of contact dermatitis. For this purpose, it is essential to know if there are any changes in the prevalences of sensitizations to different allergens over time.1,2

Patch tests constitute the fundamental method for detecting sensitization to contact allergens,3,4 serving as an essential tool for diagnosing allergic contact dermatitis (ACD).3,4 The evaluation of any patient with suspected ACD should include a standard national or international battery of patch tests and, optionally, one or more specific batteries, which may also include the patient's own products.3,4

The Spanish standard battery is a dynamic battery that is periodically updated by members of the Spanish Research Group on Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy (GEIDAC). To do this, various criteria are taken into consideration, such as the frequency of sensitization (> 0.5% to 1%), as well as other characteristics, such as whether there are emerging allergens in the dermatological medical literature available or neighboring countries, or whether they are of particular importance for a group of patients, or exposure environment.

The objective of our work is to describe the variations in temporal trends in sensitizations to allergens in the standard series of GEIDAC from 2018 through December 31, 2022.

Materials and methodsREIDAC prospectively collects the results of all consecutively patched patients in the participant centers. The data are anonymized at the source, and the registry complies with all ethical standards on informed consent and data protection legislation. In addition to the present positivities and relevancies, the registry successively collects epidemiological, clinical, and allergic variables of patients who underwent patch tests at the participant centers across this period, including the data necessary to obtain the Male, Occupational dermatitis, Atopic dermatitis, Hand dermatitis, Leg dermatitis, Facial dermatitis, Age > 40 years (MOAHLFA) index. In this study, we used data from 2018 through December 31, 2022.3

Patch tests were performed following the recommendations of the European Society of Contact Dermatitis,5 considering readings (+), (++), or (+++) as positive. Relevance was determined based on the patient's health record.

The latest update of the GEIDAC standard battery dates back to January 2022, including 4 new allergens (hydroxyethyl methacrylate, textile dye mix, linalool hydroperoxides, and limonene hydroperoxides), and removing 3 (ethylene diamine dihydrochloride, methyl dibromoglutaronitrile, and hydroxyisohexyl-3-cyclohexene-carboxaldehyde), which were not included in the current study.3

A descriptive analysis of the MOAHLFA index was performed, as well as the prevalence of each allergen, and its distribution over the years was compared. The results were graphically presented. Homogeneity comparisons were drawn using the chi-square test, and the linear trend analysis was performed using the linear trend tests for scores. For trend analysis, raw P values and MOAHLFA-adjusted values were obtained. The prevalence of each allergen in the standard battery was also presented by age and sex.

All statistical analyses were performed using the STATA v.17.0 software (Stata Corp. 2021. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17). P values < .0016 (adjusted with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons) were considered statistically significant.

REIDAC was approved by Hospitalario Universitario Insular-Materno Infantil Research Ethics Committee (2017/964) in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed a written informed consent form for participation purposes.

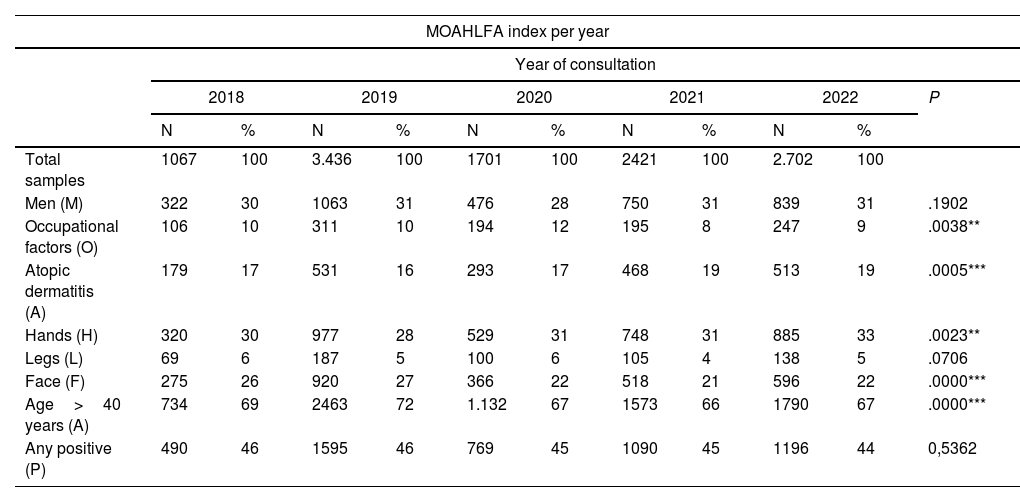

ResultsThe total number of patients included in REIDAC during the study period was 11327 participants. The distribution by years of this population, as well as the description of the MOAHLFA index by year, are included in Table 1.

Variation of MOAHLFA index on a yearly basis.

| MOAHLFA index per year | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of consultation | |||||||||||

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | P | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Total samples | 1067 | 100 | 3.436 | 100 | 1701 | 100 | 2421 | 100 | 2.702 | 100 | |

| Men (M) | 322 | 30 | 1063 | 31 | 476 | 28 | 750 | 31 | 839 | 31 | .1902 |

| Occupational factors (O) | 106 | 10 | 311 | 10 | 194 | 12 | 195 | 8 | 247 | 9 | .0038** |

| Atopic dermatitis (A) | 179 | 17 | 531 | 16 | 293 | 17 | 468 | 19 | 513 | 19 | .0005*** |

| Hands (H) | 320 | 30 | 977 | 28 | 529 | 31 | 748 | 31 | 885 | 33 | .0023** |

| Legs (L) | 69 | 6 | 187 | 5 | 100 | 6 | 105 | 4 | 138 | 5 | .0706 |

| Face (F) | 275 | 26 | 920 | 27 | 366 | 22 | 518 | 21 | 596 | 22 | .0000*** |

| Age>40 years (A) | 734 | 69 | 2463 | 72 | 1.132 | 67 | 1573 | 66 | 1790 | 67 | .0000*** |

| Any positive (P) | 490 | 46 | 1595 | 46 | 769 | 45 | 1090 | 45 | 1196 | 44 | 0,5362 |

Although there are statistically significant differences in some variables, conditioned by the large sample size, these are clinically less relevant, and when adjusting values for these differences, there are no changes in the trends reported.

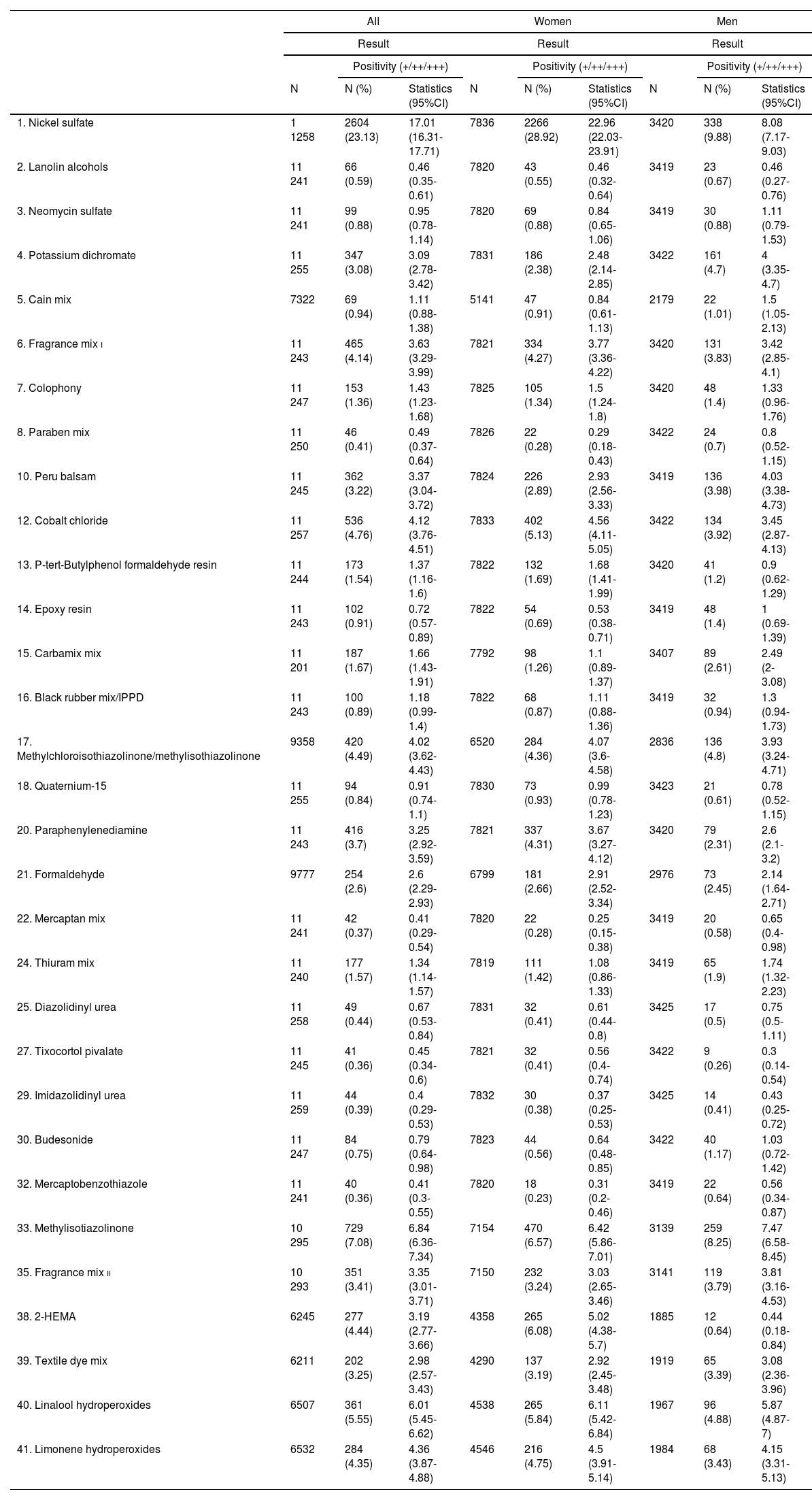

Table 2 illustrates the total positives for different allergens in the standard series of GEIDAC in the patients studied over the study years in the overall population studied, differentiated by gender, and standardized by sex and age.

Positivity rates to the different allergens included in the standard GEIDAC series in all the studied patients differentiated by sex.

| All | Women | Men | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | Result | Result | |||||||

| Positivity (+/++/+++) | Positivity (+/++/+++) | Positivity (+/++/+++) | |||||||

| N | N (%) | Statistics (95%CI) | N | N (%) | Statistics (95%CI) | N | N (%) | Statistics (95%CI) | |

| 1. Nickel sulfate | 1 1258 | 2604 (23.13) | 17.01 (16.31-17.71) | 7836 | 2266 (28.92) | 22.96 (22.03-23.91) | 3420 | 338 (9.88) | 8.08 (7.17-9.03) |

| 2. Lanolin alcohols | 11 241 | 66 (0.59) | 0.46 (0.35-0.61) | 7820 | 43 (0.55) | 0.46 (0.32-0.64) | 3419 | 23 (0.67) | 0.46 (0.27-0.76) |

| 3. Neomycin sulfate | 11 241 | 99 (0.88) | 0.95 (0.78-1.14) | 7820 | 69 (0.88) | 0.84 (0.65-1.06) | 3419 | 30 (0.88) | 1.11 (0.79-1.53) |

| 4. Potassium dichromate | 11 255 | 347 (3.08) | 3.09 (2.78-3.42) | 7831 | 186 (2.38) | 2.48 (2.14-2.85) | 3422 | 161 (4.7) | 4 (3.35-4.7) |

| 5. Cain mix | 7322 | 69 (0.94) | 1.11 (0.88-1.38) | 5141 | 47 (0.91) | 0.84 (0.61-1.13) | 2179 | 22 (1.01) | 1.5 (1.05-2.13) |

| 6. Fragrance mix i | 11 243 | 465 (4.14) | 3.63 (3.29-3.99) | 7821 | 334 (4.27) | 3.77 (3.36-4.22) | 3420 | 131 (3.83) | 3.42 (2.85-4.1) |

| 7. Colophony | 11 247 | 153 (1.36) | 1.43 (1.23-1.68) | 7825 | 105 (1.34) | 1.5 (1.24-1.8) | 3420 | 48 (1.4) | 1.33 (0.96-1.76) |

| 8. Paraben mix | 11 250 | 46 (0.41) | 0.49 (0.37-0.64) | 7826 | 22 (0.28) | 0.29 (0.18-0.43) | 3422 | 24 (0.7) | 0.8 (0.52-1.15) |

| 10. Peru balsam | 11 245 | 362 (3.22) | 3.37 (3.04-3.72) | 7824 | 226 (2.89) | 2.93 (2.56-3.33) | 3419 | 136 (3.98) | 4.03 (3.38-4.73) |

| 12. Cobalt chloride | 11 257 | 536 (4.76) | 4.12 (3.76-4.51) | 7833 | 402 (5.13) | 4.56 (4.11-5.05) | 3422 | 134 (3.92) | 3.45 (2.87-4.13) |

| 13. P-tert-Butylphenol formaldehyde resin | 11 244 | 173 (1.54) | 1.37 (1.16-1.6) | 7822 | 132 (1.69) | 1.68 (1.41-1.99) | 3420 | 41 (1.2) | 0.9 (0.62-1.29) |

| 14. Epoxy resin | 11 243 | 102 (0.91) | 0.72 (0.57-0.89) | 7822 | 54 (0.69) | 0.53 (0.38-0.71) | 3419 | 48 (1.4) | 1 (0.69-1.39) |

| 15. Carbamix mix | 11 201 | 187 (1.67) | 1.66 (1.43-1.91) | 7792 | 98 (1.26) | 1.1 (0.89-1.37) | 3407 | 89 (2.61) | 2.49 (2-3.08) |

| 16. Black rubber mix/IPPD | 11 243 | 100 (0.89) | 1.18 (0.99-1.4) | 7822 | 68 (0.87) | 1.11 (0.88-1.36) | 3419 | 32 (0.94) | 1.3 (0.94-1.73) |

| 17. Methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone | 9358 | 420 (4.49) | 4.02 (3.62-4.43) | 6520 | 284 (4.36) | 4.07 (3.6-4.58) | 2836 | 136 (4.8) | 3.93 (3.24-4.71) |

| 18. Quaternium-15 | 11 255 | 94 (0.84) | 0.91 (0.74-1.1) | 7830 | 73 (0.93) | 0.99 (0.78-1.23) | 3423 | 21 (0.61) | 0.78 (0.52-1.15) |

| 20. Paraphenylenediamine | 11 243 | 416 (3.7) | 3.25 (2.92-3.59) | 7821 | 337 (4.31) | 3.67 (3.27-4.12) | 3420 | 79 (2.31) | 2.6 (2.1-3.2) |

| 21. Formaldehyde | 9777 | 254 (2.6) | 2.6 (2.29-2.93) | 6799 | 181 (2.66) | 2.91 (2.52-3.34) | 2976 | 73 (2.45) | 2.14 (1.64-2.71) |

| 22. Mercaptan mix | 11 241 | 42 (0.37) | 0.41 (0.29-0.54) | 7820 | 22 (0.28) | 0.25 (0.15-0.38) | 3419 | 20 (0.58) | 0.65 (0.4-0.98) |

| 24. Thiuram mix | 11 240 | 177 (1.57) | 1.34 (1.14-1.57) | 7819 | 111 (1.42) | 1.08 (0.86-1.33) | 3419 | 65 (1.9) | 1.74 (1.32-2.23) |

| 25. Diazolidinyl urea | 11 258 | 49 (0.44) | 0.67 (0.53-0.84) | 7831 | 32 (0.41) | 0.61 (0.44-0.8) | 3425 | 17 (0.5) | 0.75 (0.5-1.11) |

| 27. Tixocortol pivalate | 11 245 | 41 (0.36) | 0.45 (0.34-0.6) | 7821 | 32 (0.41) | 0.56 (0.4-0.74) | 3422 | 9 (0.26) | 0.3 (0.14-0.54) |

| 29. Imidazolidinyl urea | 11 259 | 44 (0.39) | 0.4 (0.29-0.53) | 7832 | 30 (0.38) | 0.37 (0.25-0.53) | 3425 | 14 (0.41) | 0.43 (0.25-0.72) |

| 30. Budesonide | 11 247 | 84 (0.75) | 0.79 (0.64-0.98) | 7823 | 44 (0.56) | 0.64 (0.48-0.85) | 3422 | 40 (1.17) | 1.03 (0.72-1.42) |

| 32. Mercaptobenzothiazole | 11 241 | 40 (0.36) | 0.41 (0.3-0.55) | 7820 | 18 (0.23) | 0.31 (0.2-0.46) | 3419 | 22 (0.64) | 0.56 (0.34-0.87) |

| 33. Methylisotiazolinone | 10 295 | 729 (7.08) | 6.84 (6.36-7.34) | 7154 | 470 (6.57) | 6.42 (5.86-7.01) | 3139 | 259 (8.25) | 7.47 (6.58-8.45) |

| 35. Fragrance mix ii | 10 293 | 351 (3.41) | 3.35 (3.01-3.71) | 7150 | 232 (3.24) | 3.03 (2.65-3.46) | 3141 | 119 (3.79) | 3.81 (3.16-4.53) |

| 38. 2-HEMA | 6245 | 277 (4.44) | 3.19 (2.77-3.66) | 4358 | 265 (6.08) | 5.02 (4.38-5.7) | 1885 | 12 (0.64) | 0.44 (0.18-0.84) |

| 39. Textile dye mix | 6211 | 202 (3.25) | 2.98 (2.57-3.43) | 4290 | 137 (3.19) | 2.92 (2.45-3.48) | 1919 | 65 (3.39) | 3.08 (2.36-3.96) |

| 40. Linalool hydroperoxides | 6507 | 361 (5.55) | 6.01 (5.45-6.62) | 4538 | 265 (5.84) | 6.11 (5.42-6.84) | 1967 | 96 (4.88) | 5.87 (4.87-7) |

| 41. Limonene hydroperoxides | 6532 | 284 (4.35) | 4.36 (3.87-4.88) | 4546 | 216 (4.75) | 4.5 (3.91-5.14) | 1984 | 68 (3.43) | 4.15 (3.31-5.13) |

IPPD, N-isopropyl-n-phenyl-phenylenediamine; 2-HEMA, hydroxyethyl methacrylate; Statistics (95%CI): age and sex standardized percentage (95% confidence interval)

As can be seen, the allergens that showed a higher overall sensitization frequency across the study period were nickel sulfate, methylisothiazolinone, cobalt chloride, methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone (MCI/MI), and fragrance mix i. Some gender differences were seen while for women, the most frequently positive allergens were nickel sulfate, methylisothiazolinone, cobalt chloride, MCI/MI, fragrance mix i, and paraphenylenediamine (PPD), for men, they were nickel sulfate, MCI/MI, and potassium dichromate, with lower sensitization to PPD in men compared to in women (2.31 vs 3.31), and higher sensitization to potassium dichromate (4.7 vs 2.38), among other differences. The sensitization frequency to the allergens added in January 2022 in the studied patients was 4.44% for hydroxyethyl methacrylate, 2.58% for textile dye mix, 4.59% for linalool hydroperoxides, and 3.92% for limonene hydroperoxides.

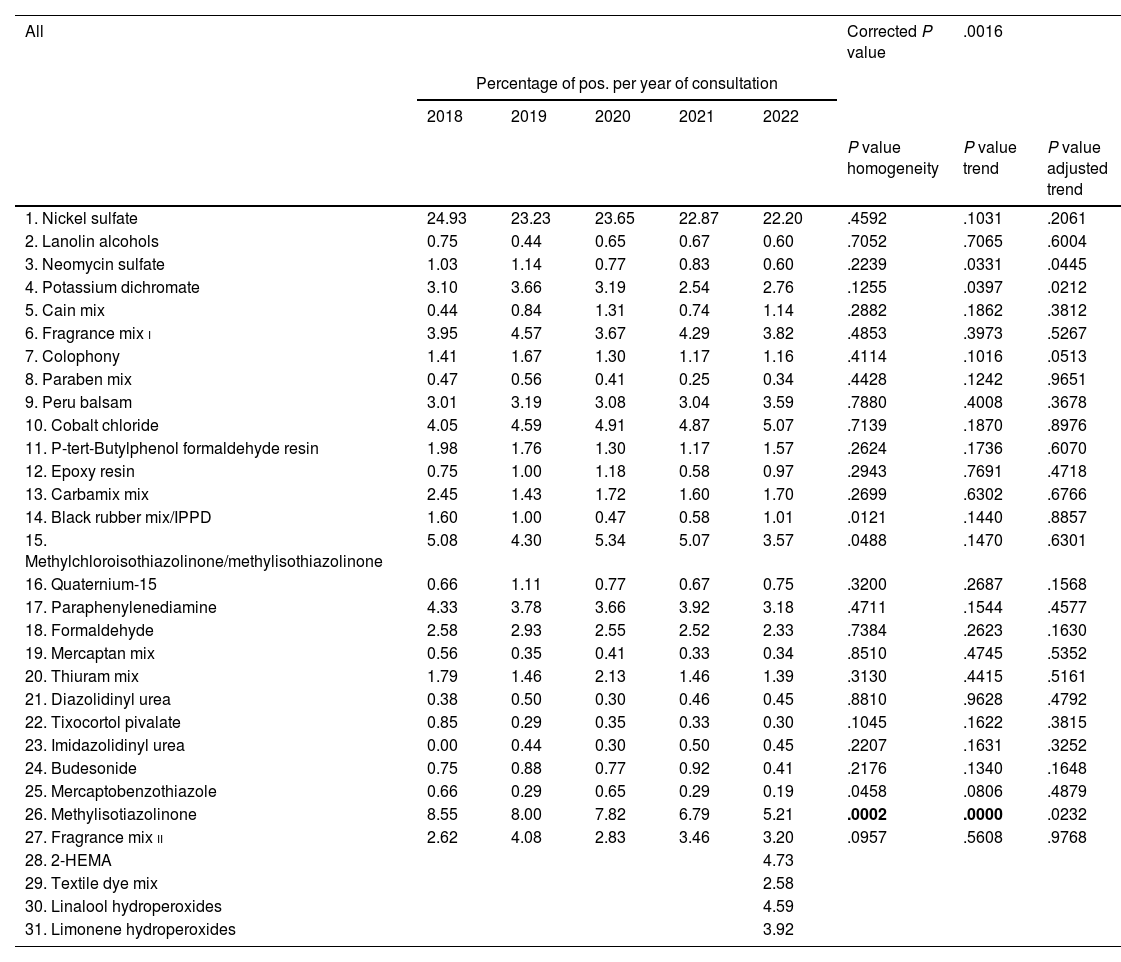

Table 3 shows the percentage of positives for different allergens included in the standard GEIDAC series across different study years. The allergens recently included in the GEIDAC standard battery are included at the end of this table; since they were not systematically patched in the early years and, therefore, were studied in a much smaller number of patients, their data prior to their inclusion in 2022 are not included in the trend study.

Percentage of positivity for various allergens included in the standard GEIDAC series across the study years.

| All | Corrected P value | .0016 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of pos. per year of consultation | ||||||||

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||||

| P value homogeneity | P value trend | P value adjusted trend | ||||||

| 1. Nickel sulfate | 24.93 | 23.23 | 23.65 | 22.87 | 22.20 | .4592 | .1031 | .2061 |

| 2. Lanolin alcohols | 0.75 | 0.44 | 0.65 | 0.67 | 0.60 | .7052 | .7065 | .6004 |

| 3. Neomycin sulfate | 1.03 | 1.14 | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.60 | .2239 | .0331 | .0445 |

| 4. Potassium dichromate | 3.10 | 3.66 | 3.19 | 2.54 | 2.76 | .1255 | .0397 | .0212 |

| 5. Cain mix | 0.44 | 0.84 | 1.31 | 0.74 | 1.14 | .2882 | .1862 | .3812 |

| 6. Fragrance mix i | 3.95 | 4.57 | 3.67 | 4.29 | 3.82 | .4853 | .3973 | .5267 |

| 7. Colophony | 1.41 | 1.67 | 1.30 | 1.17 | 1.16 | .4114 | .1016 | .0513 |

| 8. Paraben mix | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.41 | 0.25 | 0.34 | .4428 | .1242 | .9651 |

| 9. Peru balsam | 3.01 | 3.19 | 3.08 | 3.04 | 3.59 | .7880 | .4008 | .3678 |

| 10. Cobalt chloride | 4.05 | 4.59 | 4.91 | 4.87 | 5.07 | .7139 | .1870 | .8976 |

| 11. P-tert-Butylphenol formaldehyde resin | 1.98 | 1.76 | 1.30 | 1.17 | 1.57 | .2624 | .1736 | .6070 |

| 12. Epoxy resin | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.18 | 0.58 | 0.97 | .2943 | .7691 | .4718 |

| 13. Carbamix mix | 2.45 | 1.43 | 1.72 | 1.60 | 1.70 | .2699 | .6302 | .6766 |

| 14. Black rubber mix/IPPD | 1.60 | 1.00 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 1.01 | .0121 | .1440 | .8857 |

| 15. Methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone | 5.08 | 4.30 | 5.34 | 5.07 | 3.57 | .0488 | .1470 | .6301 |

| 16. Quaternium-15 | 0.66 | 1.11 | 0.77 | 0.67 | 0.75 | .3200 | .2687 | .1568 |

| 17. Paraphenylenediamine | 4.33 | 3.78 | 3.66 | 3.92 | 3.18 | .4711 | .1544 | .4577 |

| 18. Formaldehyde | 2.58 | 2.93 | 2.55 | 2.52 | 2.33 | .7384 | .2623 | .1630 |

| 19. Mercaptan mix | 0.56 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.34 | .8510 | .4745 | .5352 |

| 20. Thiuram mix | 1.79 | 1.46 | 2.13 | 1.46 | 1.39 | .3130 | .4415 | .5161 |

| 21. Diazolidinyl urea | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.46 | 0.45 | .8810 | .9628 | .4792 |

| 22. Tixocortol pivalate | 0.85 | 0.29 | 0.35 | 0.33 | 0.30 | .1045 | .1622 | .3815 |

| 23. Imidazolidinyl urea | 0.00 | 0.44 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.45 | .2207 | .1631 | .3252 |

| 24. Budesonide | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.92 | 0.41 | .2176 | .1340 | .1648 |

| 25. Mercaptobenzothiazole | 0.66 | 0.29 | 0.65 | 0.29 | 0.19 | .0458 | .0806 | .4879 |

| 26. Methylisotiazolinone | 8.55 | 8.00 | 7.82 | 6.79 | 5.21 | .0002 | .0000 | .0232 |

| 27. Fragrance mix ii | 2.62 | 4.08 | 2.83 | 3.46 | 3.20 | .0957 | .5608 | .9768 |

| 28. 2-HEMA | 4.73 | |||||||

| 29. Textile dye mix | 2.58 | |||||||

| 30. Linalool hydroperoxides | 4.59 | |||||||

| 31. Limonene hydroperoxides | 3.92 | |||||||

IPPD, N-isopropyl-n-phenyl-phenylenediamine; 2-HEMA, hydroxyethyl methacrylate; Pos.: positivity

Data with statistically significant differences highlighted in bold.

We can see how the percentage of positives for methylisothiazolinone decreases over time, with an orderly trend.

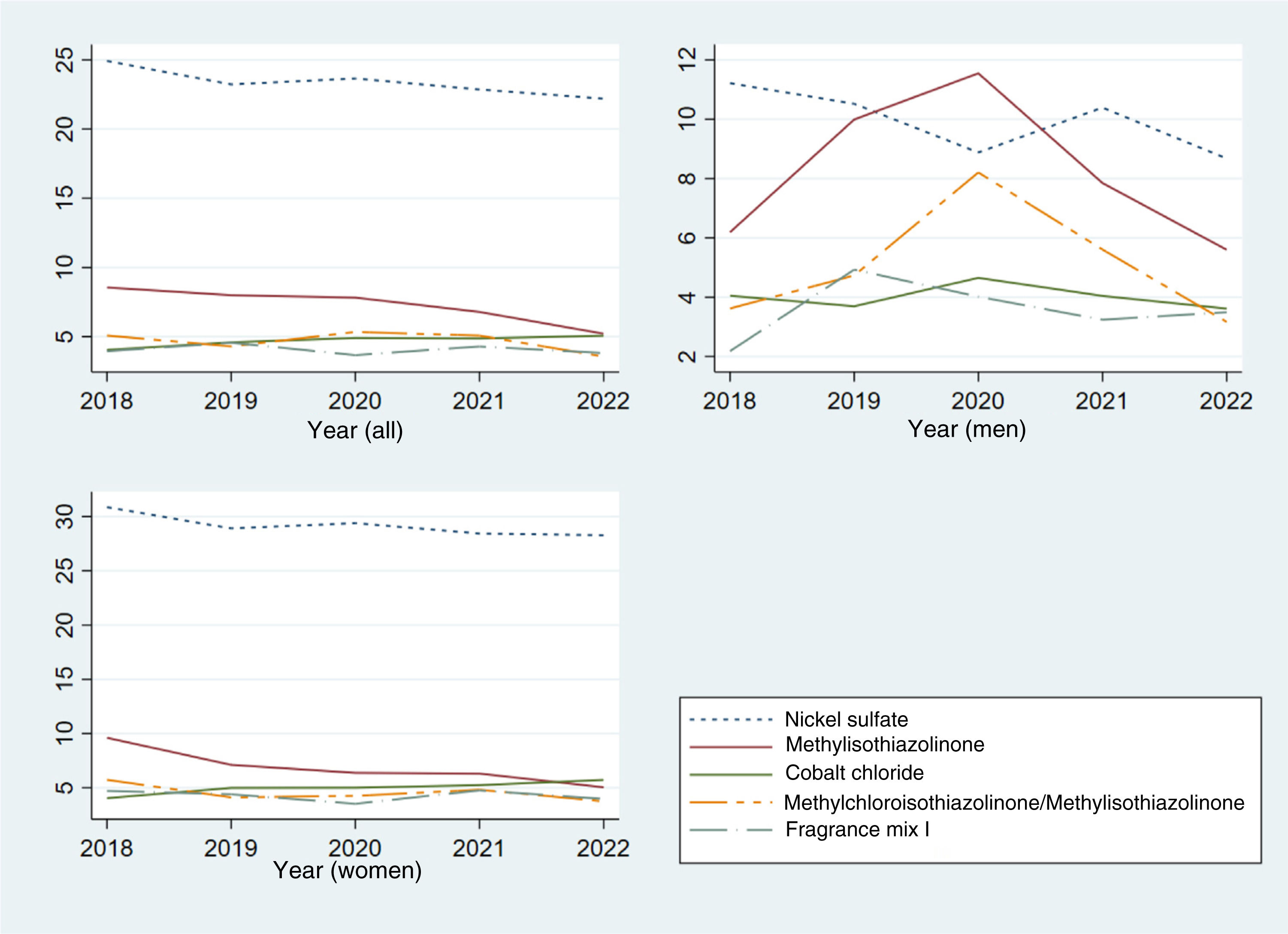

The figures below represent the variation in the percentage of positives for different allergens across the study years, both globally and differentiated by gender.

Figure 1 includes allergens with sensitization rates > 4% (nickel sulfate, methylisothiazolinone, cobalt chloride, MCI/MI, and fragrance mix I).

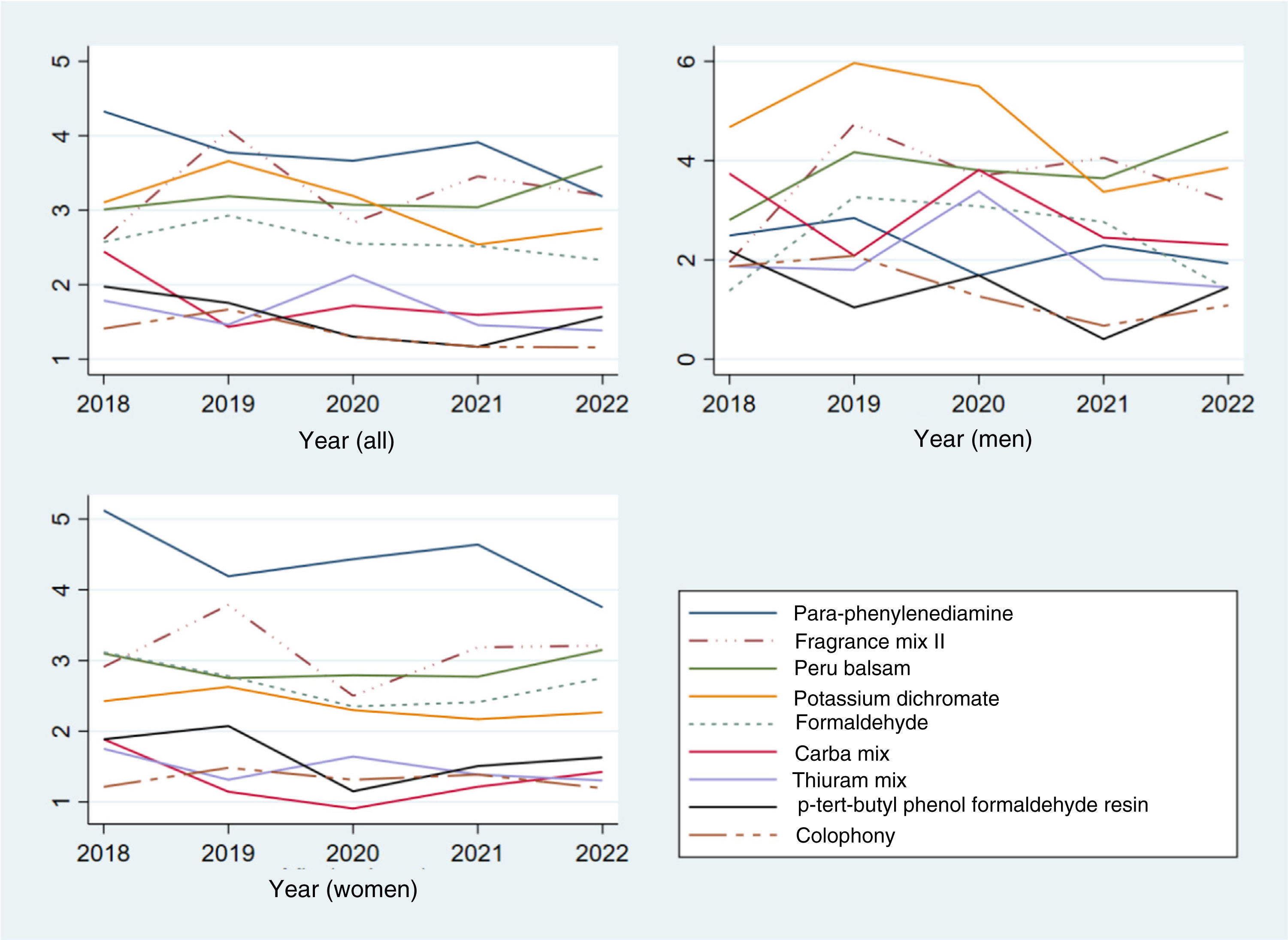

The allergens that showed sensitization frequencys ranging from 1% to 4% during the study period were PPD, fragrance mix II, balsam of Peru, potassium dichromate, formaldehyde, carbamate mix, thiuram mix, p-tert-butylphenol-formaldehyde resin, and rosin, as shown in Figure 2.

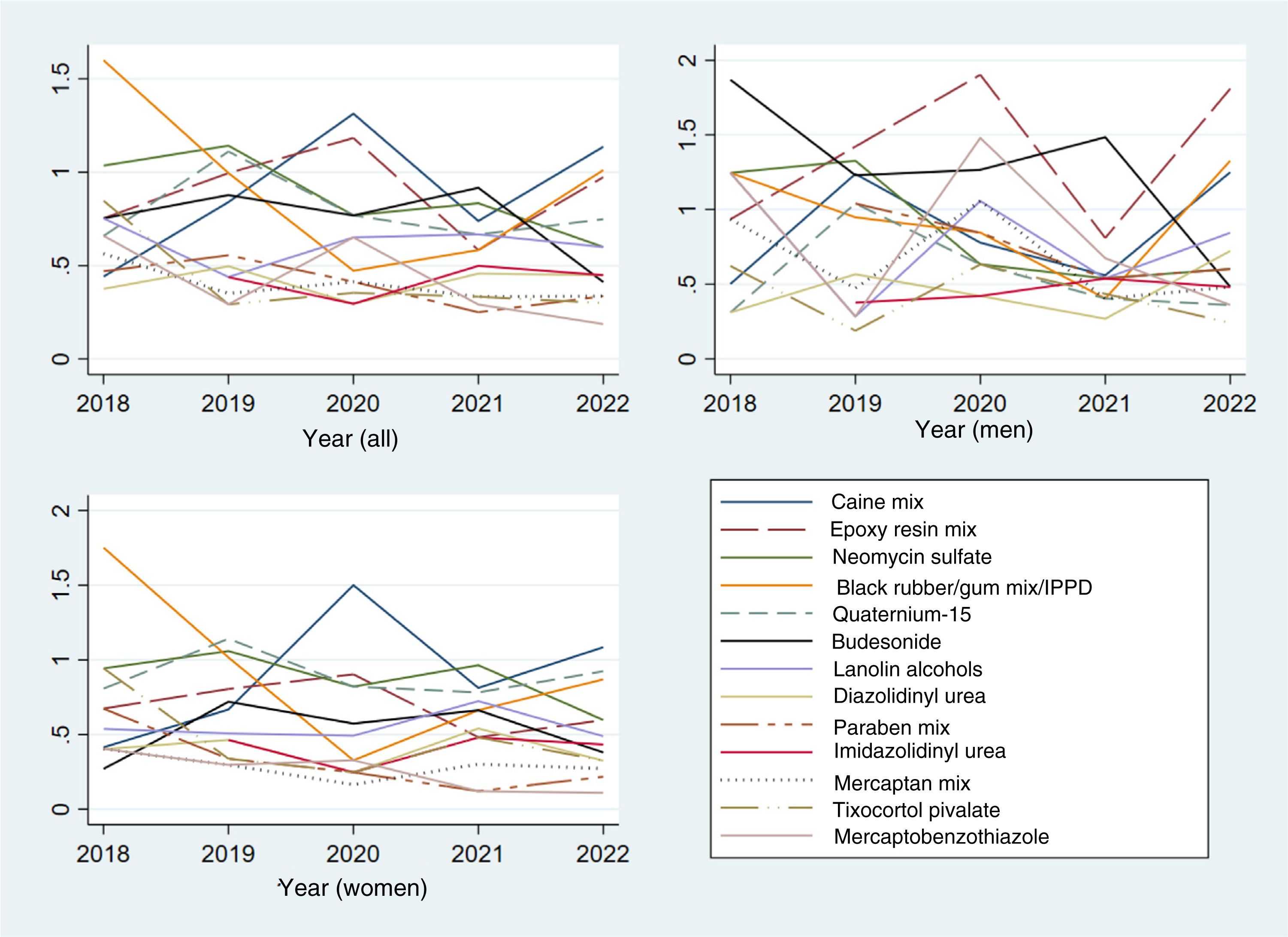

Figure 3 illustrates the variation in the percentage of positive results over the years for the remaining allergens, each of which had an overall sensitization frequency < 1%.

DiscussionEpidemiological surveillance in contact dermatitis is key to understand the variations in sensitizations to different allergens over the years, thereby enabling the implementation of proper measures for their prevention at both individual and community levels. In Spain, such surveillance is one of the objectives of REIDAC

In 1977, the first national epidemiological study of this kind was published, including 2806 patients studied through patch tests.2 The most frequently positive allergens at that time were nickel, potassium dichromate, tetramethylthiuram disulfide, PPD, a mixture of mercaptans, and wood tar extracts. Since then, various changes in exposure have led to modifications in the allergens studied (with several changes made to the GEIDAC standard series),3,4 and differences in sensitization frequencies. However, some of the allergens that were already common in those years continue to be so today. In 2011, another publication of 1161 patients from 5 national centers1 claimed that the most frequently positive allergens were nickel sulfate (25.88%), potassium dichromate (5.31%), cobalt (5.10%), a mixture of fragrances (4.64%), and balsam of Peru (4.44%). Also, there is a recent publication from our region on a specific population from Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, Spain which identified nickel sulfate, MCI/MI, methylisothiazolinone, PPD, and potassium dichromate as the most frequent allergens, even at higher frequencies than those reported at national level.6

In the international scientific medical literature available, there are other publications that attempt to capture changes in the percentage of sensitization to different allergens over the years in a similar way. In most of these series, the changes seen across years are not systematically recorded, and they are not always collected prospectively. Some series pertain to other populations,7 some of which, despite spanning across many more years, include fewer patients.8 Additionally, there are several European publications9–15 that either focus on data from years prior to ours or, in addition to that, focus on specific groups of allergic contact eczemas, such as those associated with occupational exposure,14 or due to specific allergens.15

With the current technology, a real-time approach to the most common allergens in Spain is possible.16

Among the results obtained, the persistence of high sensitization to nickel sulfate stands out, as mentioned earlier. In fact, it was already documented the early studies conducted in Spain (25.88),12 as well as in other European studies (23.98%).17 Nickel is a metal found in alloys, being nickel salts responsible for dermatitis, promoting their release and penetration into the skin primarily facilitated by sweating. In 1994, European regulations were passed to control the release of nickel in jewelry, but they did not become effective until 2021. Despite the ongoing high sensitization, many of the positive cases detected today do not seem to be relevant today.

PPD continues to exhibit high sensitization in our environment, especially among women, as mentioned earlier. In a recent publication on PPD sensitization across various Spanish centers,18 it remained fairly stable at nearly 4% of all patch-tested patients from 2004 through 2014, and no significant changes reported despite the regulation implemented in 2009 regarding hair dyes (reducing its maximum concentration from 6% down to 2%). Several hypotheses have been proposed for the persistence of this sensitization, such as the maintenance of the habit of getting temporary henna tattoos, which are often adulterated with PPD, whose concentration has not yet been regulated,19 or lifestyle changes leading to more and more patients using cosmetics containing PPD at younger ages.

In our study, sensitization to fragrance mix I also persists at a high level, despite regulatory changes introduced in the mandatory labeling of certain fragrances. Also, it remains at levels similar to those reported in previous national series (4.99%),1 and recent European studies (3.4%).17

High sensitization to isothiazolinones, both MCI/MI (which remains high throughout across the study years) and methylisothiazolinone should also be mentioned here. In the case of the latter, although sensitization remains high, there is a drop in sensitization frequency across the years, both in raw values and when adjusted for sex and age being the only allergen with statistically significant changes reported.

Methylisothiazolinone is a derivative of isothiazolinones, and is widely used as a preservative in rinse-off cosmetics, household detergents, water-based paints, and industrial products. Sensitization to it occurs both in the domestic environment—mainly due to exposure to cosmetics and household detergents—and in the workplace, especially among cleaning workers.

The epidemic of sensitization to methylisothiazolinone at the beginning of the 21st century is well known.20–22 As a result, after recognizing the problem, the use of methylisothiazolinone was ill-advised in rinse-off cosmetics by the European cosmetic industry at the end of 2013. At the same time, the Scientific Committee on Consumer Safety reevaluated the risk, which lead to the recommendation to ban the use of methylisothiazolinone in rinse-off cosmetics and keep the maximum allowable level to 15ppm in leave-on cosmetics. Although it took time for this recommendation to translate into an actual regulation, and the regulation again allowed for transition periods, a change in sensitization trends could be expected as confirmed by our most recent data.

In the United States, according to the most recent data from the North American Contact Dermatitis Group, the highest prevalence of sensitization to isothiazolinones occurred later than it did in Europe.23 While in Europe, sensitization to MCI/MI from 2013 through 2014 reached levels of 5.4% to 7.6%, before dropping in 2017-2018 down to 3.2%-4.4%,24,25 in the United States, positivity to MCI/MI increased from 2.5% in 2009-2010 up to 10.8% in 2017-2018. The same thing happened for methylisothiazolinone, where reactions decreased in Europe down to 3.4%-5.5% compared to 15% in the North American Contact Dermatitis Group during 2017-2018. This is likely due to the lack of regulations on the use of isothiazolinones in cosmetics across the United States.

According to recent data published by REIDAC,22 sensitization to both MI and MCI/MI is associated with being an active worker, hand dermatitis, the use of detergents, and being older than 40 years.

Some other changes in sensitization trends can be seen, but none of them are significant. For example, in the case of neomycin, there is a downward trend since data collection began, although it is not significant, possibly indicating reduced use of topical drugs including combinations of antibiotics and other agents (corticosteroids, antifungals, etc.). In Spain, prescriptions for topical products combining corticosteroids and antibiotics have not been funded for years.

Similarly, we can see also non-significant downward trend in sensitization to potassium dichromate. The most common sources of exposure to potassium dichromate are wet cement and chromium-tanned leather products. Since 2005, the use of cements with > 2ppm of hexavalent chromium has been restricted, and a decrease in sensitization has been detected based on historical data and in certain regions.6,26 The decrease in sensitization is likely related to this regulation, and with the improved preventive measures implemented by construction workers. Additionally, a probable decrease in the use of leather footwear in recent years may have also contributed to its decline, although there is not enough data to confirm this hypothesis to date.

Our study included data on allergens that have been more recently added to the standard GEIDAC panel, and a high overall level of sensitization to all of them can be observed (hydroxyethyl methacrylate, textile dye mix, linalool hydroperoxides, and limonene hydroperoxides).

For a specific population, changes in sensitization to different allergens often depend on the chemical characteristics of these allergens (which, overall, do not change), and the degree of exposure to them. Therefore, assuming that the characteristics of our population have remained fairly consistent across the years (no significant differences in the MOAHLFA data across the years can be seen, as shown in Table 1, except perhaps for the face, where a decrease was seen in the 2020-2022 compared to previous years, possibly influenced by the use of masks during the COVID pandemic years), the differences detected in sensitization should be attributed to changes in various exposures.

ConclusionsAccording to the data obtained in our study, the persistence of high sensitization to allergens such as nickel, MCI/MI, and fragrance mix I is noteworthy. Only a significant downward trend for methylisothiazolinone was found.

We want to emphasize the importance of multicenter registries, which allow us to gather data on a large scale and thereby detect trends. This enables us to observe potential increases in sensitization to certain allergens, prompting us to consider the need for measures to reduce this. Additionally, as is the case with methylisothiazolinone, it helps us verify the effectiveness of the measures taken to reduce sensitization.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.