Paraffin-embedded margin-controlled Mohs micrographic surgery (PMMS) includes various procedures such as slow Mohs or deferred Mohs technique, the Muffin and Tübingen techniques, and staged margin excision, or the spaghetti technique. PMMS is a variation of conventional Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) that allows histopathological examination with delayed margin control. PMMS requires minimum training and may be adopted by any hospital. The setback is that PMMS can require procedures across multiple days. PMMS lowers the rate of recurrence of basal cell carcinoma vs wide local excision in high-risk basal cell carcinoma, and improves the rates of recurrence and survival in lentigo maligna. PMMS can be very useful in high-risk squamous cell carcinoma treatment. Finally, it is a promising technique to treat infrequent skin neoplasms, such as dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, or extramammary Paget's disease, among others. In this article, we present a literature narrative review on PMMS, describing techniques and indications, and highlighting long-term outcomes.

La cirugía micrográfica con márgenes controlados en parafina (PMMS) incluye diversos procedimientos como el slow Mohs o Mohs en diferido, la técnica del Muffin, la torta de Tübingen, y la escisión de márgenes por etapas o espagueti. La PMMS es una modificación de la cirugía de Mohs convencional (MMS) con estudio histológico en diferido. La PMMS requiere una formación mínima y podría ejecutarse en cualquier hospital. Como inconveniente, la PMMS puede requerir realizar procedimientos en distintos días. La PMMS ha demostrado una tasa de recurrencia más baja en comparación con la exéresis convencional en el carcinoma basocelular, y una menor tasa de recurrencia y supervivencia más prolongada en el lentigo maligno. La PMMS también es de gran utilidad en el carcinoma de células escamosas, y en tumores infrecuentes. En este artículo, presentamos una revisión narrativa sobre la PMMS, describiendo técnicas e indicaciones, y destacando sus resultados a largo plazo.

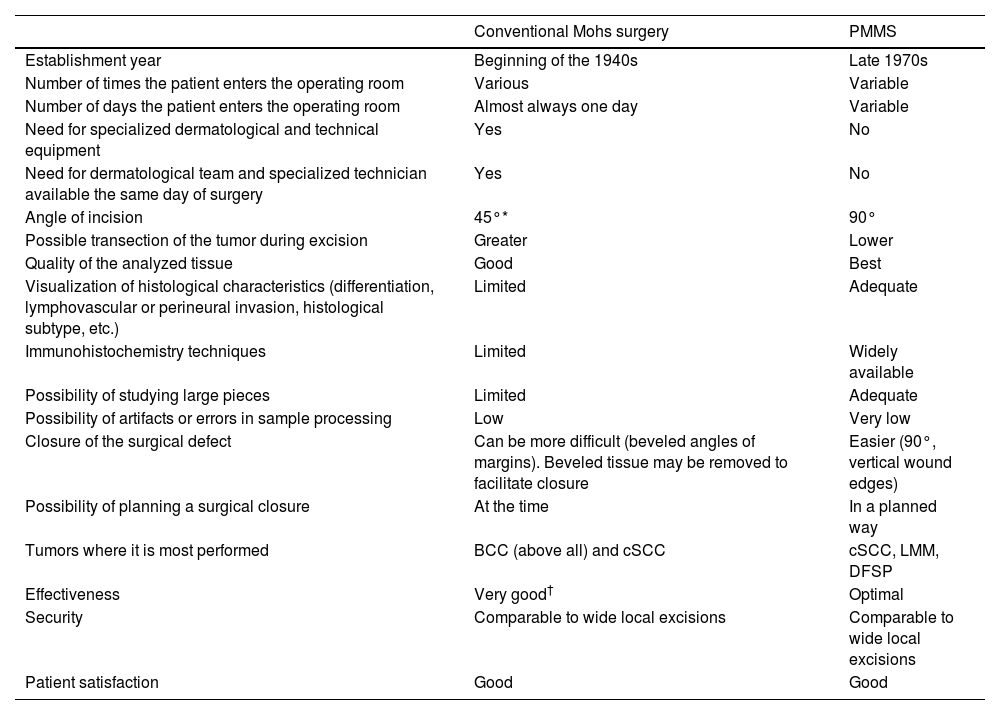

Surgical treatment with free margins (R0 resection) is the treatment of choice for most localized skin malignancies.1 Micrographic surgery with margin control or Mohs surgery (MMS) has shown the highest cure rate and lowest rate of recurrences in the management of multiple skin tumors.2–5 MMS has numerous indications, and has gone through multiple variations since its original description.6 In addition to its advantages in terms of lower local recurrence rates, recent studies have suggested lower rates of locoregional recurrence, with reduced rates of in-transit metastases or satellitosis in head and neck melanoma, as well as a lower rate of distant metastases, and even increased survival.7–9 Despite its numerous advantages, MMS has several drawbacks. Among these are high cost, the need for a surgical and technical team available with advanced training, adequate equipment, and the time needed when several stages are required.10,11 In response to these difficulties, especially when it comes to relying on a specialized technical team at the precise moment of surgery for in vivo analysis, at the end of the 1970s, variations to the original MMS technique started being developed to allow for deferred analyses, using paraffin-fixed sections. These techniques have been reported in the scientific medical literature as deferred Mohs, slow Mohs, 3D histology, complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment with permanent sections, Muffin technique, perimeter technique, quadrant technique, Tübingen technique, rush paraffin sections, staged marginal and central excision technique, or paraffin sections with tissue mapping before delayed surgical defect closure. Although these techniques are different, they analyze 100% of the margins of the tumor, its sides and deep inside the tumor (conventional histopathological examination analyzes <1% of the margins), and are performed through 90° incisions. In all of these procedures, the excised tissue is marked for precise topographic orientation.12,13 These techniques can be performed with both frozen and paraffin sections. However, in the routine clinical practice, they are mostly performed using paraffin-fixed sections. To avoid confusing nomenclature, we will refer to all variations of MMS with paraffin sections as paraffin-embedded margin-controlled Mohs micrographic surgery (PMMS). With this technique, complete analysis of the surgically excised piece can be achieved, as with the MMS without having to perform an analysis immediately after the surgical procedure. This deferred analysis has shown its effectiveness not only in basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC), but also in others in which immediate (fresh) analysis is more complex and can require immunohistochemical analysis, such as lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM), atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX), dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) or extramammary Paget's disease, among others.14–16 A comparison between MMS surgery and PMMS is shown in Table 1. In this article we will review different types of PMMS, as well as their indications and outcomes in terms of local recurrence in the surgical treatment of diverse skin malignancies.

Comparison between conventional Mohs surgery and paraffin-embedded microscopically controlled surgery.

| Conventional Mohs surgery | PMMS | |

|---|---|---|

| Establishment year | Beginning of the 1940s | Late 1970s |

| Number of times the patient enters the operating room | Various | Variable |

| Number of days the patient enters the operating room | Almost always one day | Variable |

| Need for specialized dermatological and technical equipment | Yes | No |

| Need for dermatological team and specialized technician available the same day of surgery | Yes | No |

| Angle of incision | 45°* | 90° |

| Possible transection of the tumor during excision | Greater | Lower |

| Quality of the analyzed tissue | Good | Best |

| Visualization of histological characteristics (differentiation, lymphovascular or perineural invasion, histological subtype, etc.) | Limited | Adequate |

| Immunohistochemistry techniques | Limited | Widely available |

| Possibility of studying large pieces | Limited | Adequate |

| Possibility of artifacts or errors in sample processing | Low | Very low |

| Closure of the surgical defect | Can be more difficult (beveled angles of margins). Beveled tissue may be removed to facilitate closure | Easier (90°, vertical wound edges) |

| Possibility of planning a surgical closure | At the time | In a planned way |

| Tumors where it is most performed | BCC (above all) and cSCC | cSCC, LMM, DFSP |

| Effectiveness | Very good† | Optimal |

| Security | Comparable to wide local excisions | Comparable to wide local excisions |

| Patient satisfaction | Good | Good |

Abbreviations: PMMS, paraffin-embedded microscopically controlled surgery; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; cSCC, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma; LMM, lentigo maligna melanoma; DFSP, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.

A narrative search of the literature was conducted in Medline and Google Scholar during May 2023 using the keyterms ‘Mohs surgery’, ‘Mohs surgery in paraffin’, ‘slow Mohs’, ‘3D histology’, ‘complete circumferential peripherals and deep margin assessment with permanent sections’, ‘Muffin-technique surgery’, ‘perimeter technique surgery’, ‘quadrant technique surgery’, ‘Tubingen technique’, ‘rush paraffin sections’, ‘staged marginal and central excision technique’, ‘spaghetti technique’ whether isolated or in combination with the keywords ‘basal cell carcinoma’, ‘squamous cell carcinoma’, ‘melanoma’, ‘lentigo maligna melanoma’, ‘acral lentiginous melanoma’, ‘dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans’, ‘atypical fibroxanthoma’, ‘microcystic adnexal carcinoma’, ‘Merkel cell carcinoma’, ‘extramammary Paget's disease’, and ‘cutaneous adnexal tumors’. Prospective and retrospective studies, case series of ≥10 patients, clinical trials, and systematic reviews (SR) and meta-analyses (MA) were included. Regarding rare tumors, some series with <10 patients and satisfactory methodological quality were collected. Two of the authors (MMP and DMC) performed the search and selected the articles.

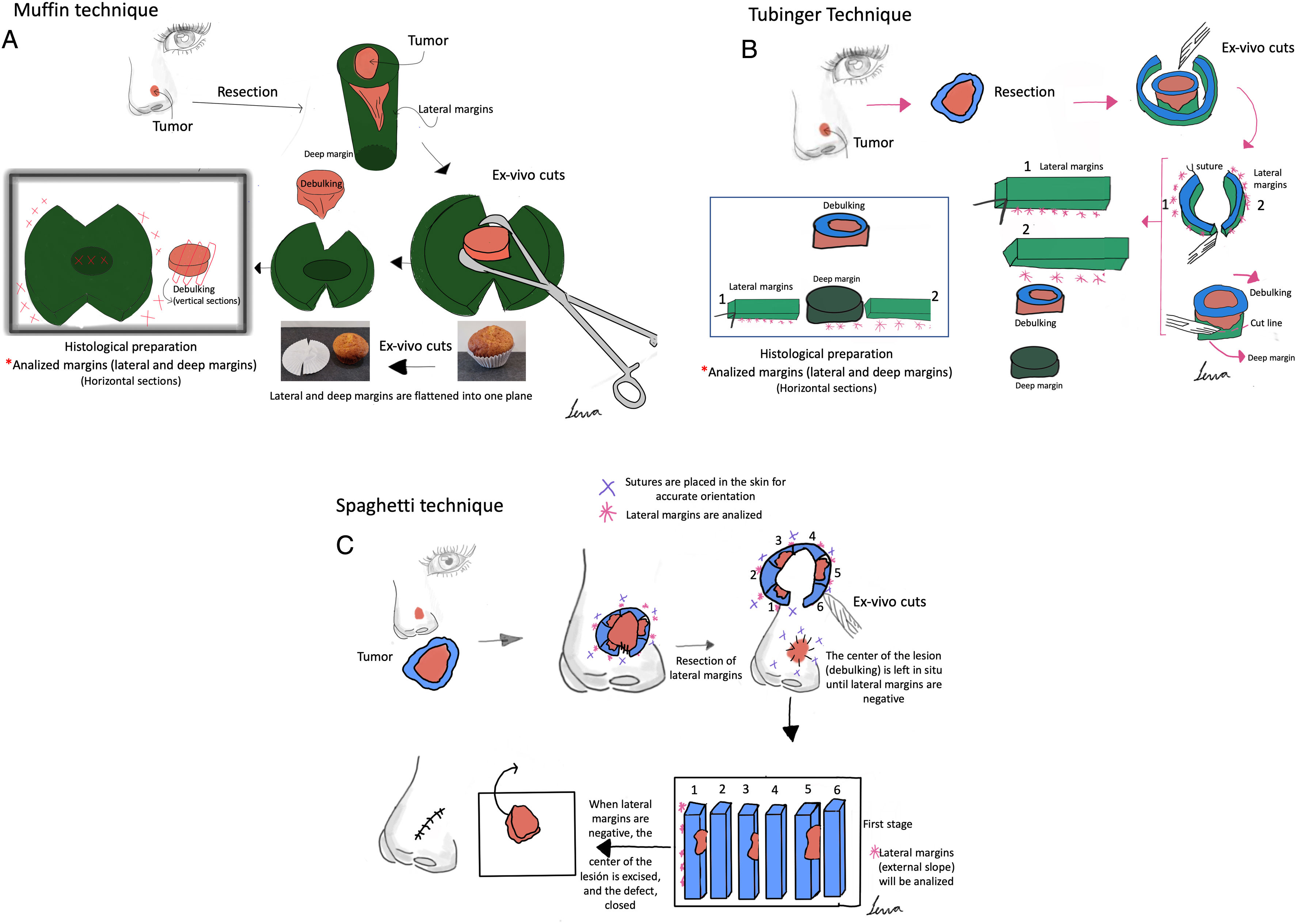

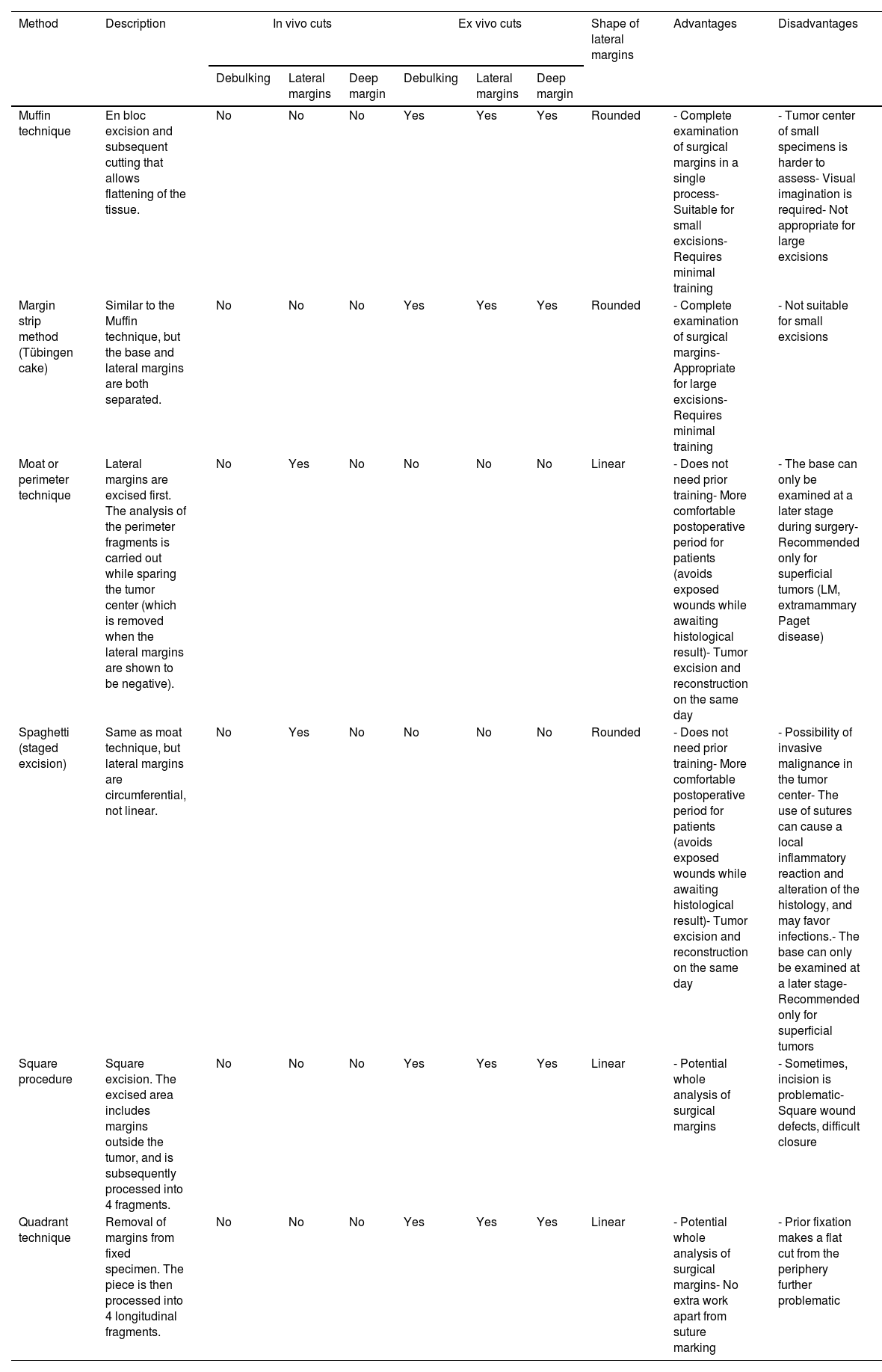

ResultsParaffin-embedded margin-controlled techniquesNumerous variants of PMMS were found, all of which had in common the deferred analysis of the surgical piece. Although the terms used are sometimes interchangeable, they differ mainly in the method of cutting the piece (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Paraffin-embedded microscopically controlled surgery, advantages and disadvantages.

| Method | Description | In vivo cuts | Ex vivo cuts | Shape of lateral margins | Advantages | Disadvantages | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debulking | Lateral margins | Deep margin | Debulking | Lateral margins | Deep margin | |||||

| Muffin technique | En bloc excision and subsequent cutting that allows flattening of the tissue. | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Rounded | - Complete examination of surgical margins in a single process- Suitable for small excisions- Requires minimal training | - Tumor center of small specimens is harder to assess- Visual imagination is required- Not appropriate for large excisions |

| Margin strip method (Tübingen cake) | Similar to the Muffin technique, but the base and lateral margins are both separated. | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Rounded | - Complete examination of surgical margins- Appropriate for large excisions- Requires minimal training | - Not suitable for small excisions |

| Moat or perimeter technique | Lateral margins are excised first. The analysis of the perimeter fragments is carried out while sparing the tumor center (which is removed when the lateral margins are shown to be negative). | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Linear | - Does not need prior training- More comfortable postoperative period for patients (avoids exposed wounds while awaiting histological result)- Tumor excision and reconstruction on the same day | - The base can only be examined at a later stage during surgery- Recommended only for superficial tumors (LM, extramammary Paget disease) |

| Spaghetti (staged excision) | Same as moat technique, but lateral margins are circumferential, not linear. | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Rounded | - Does not need prior training- More comfortable postoperative period for patients (avoids exposed wounds while awaiting histological result)- Tumor excision and reconstruction on the same day | - Possibility of invasive malignance in the tumor center- The use of sutures can cause a local inflammatory reaction and alteration of the histology, and may favor infections.- The base can only be examined at a later stage- Recommended only for superficial tumors |

| Square procedure | Square excision. The excised area includes margins outside the tumor, and is subsequently processed into 4 fragments. | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Linear | - Potential whole analysis of surgical margins | - Sometimes, incision is problematic- Square wound defects, difficult closure |

| Quadrant technique | Removal of margins from fixed specimen. The piece is then processed into 4 longitudinal fragments. | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Linear | - Potential whole analysis of surgical margins- No extra work apart from suture marking | - Prior fixation makes a flat cut from the periphery further problematic |

Abbreviation: LM: lentigo maligna.

Paraffin-embedded margin-controlled Mosh micrographic surgery. (A) Muffin technique. After resection, deep incisions are performed at 6 and 12 o’clock, and the lateral margins are then folded laterally to a horizontal plane (same plane of the base), which is then cut after being formaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded in a horizontal plane starting from the bottom of the specimen. A representative cross-section through the central part of the tumor (debulking) can aid in diagnostic classification. (B) Tübingen technique. After resection, a narrow (1–3mm) lateral marginal strip is cut around the entire perimeter of the tumor edge. The strip is then laid flat on the peripheral side and then cut into pieces that are placed in routine cassettes for histopathological examination. Subsequently, a horizontal section is cut from the bottom of the excised sample and also positioned flat on a histology cassette. (C) Spaghetti technique. A narrow band of skin, ‘the spaghetti’, is resected 3–5mm beyond the clinically/dermoscopically apparent perimeter of the tumor and sent for histopathological examination without tumor removal. The same procedure is repeated beyond the segments which are shown to be “tumor positive” and then until all lateral margins are tumor-free.

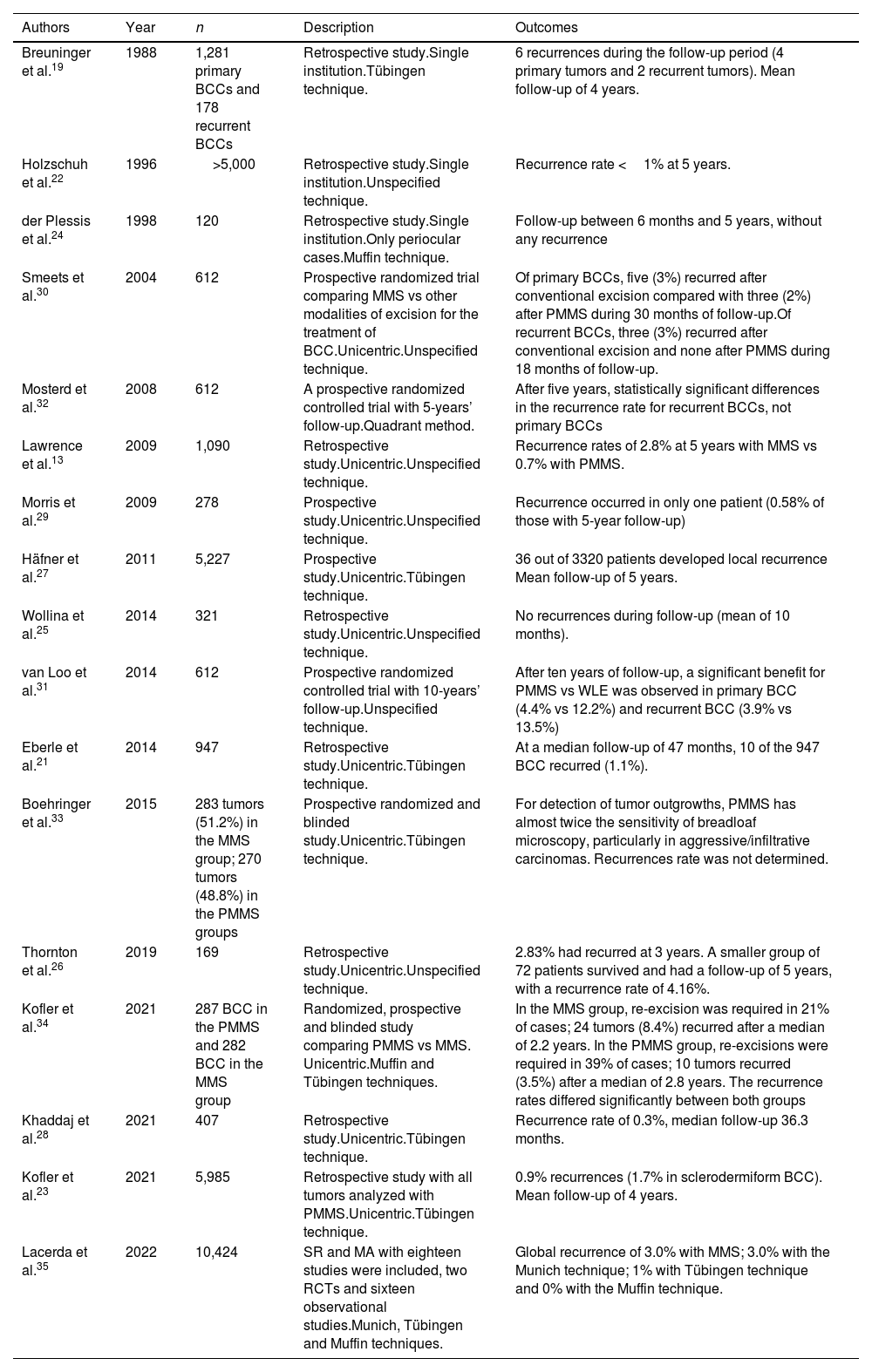

BCC is the most common malignant tumor in humans. Inadequate treatment or incomplete excisions can lead to infiltrating tumors that can produce significant functional and esthetic complications.17 MMS is optimally suited for BCC, especially vs more aggressively growing tumor variants, BCC recurrences, and tumors presenting with additional risk factors. Traditionally, MMS has been performed with frozen sections.17–19 We found 17 studies on the use of PMMS to treat BCC: 8 retrospective studies,13,20–26 3 prospective studies,27–29 5 randomized clinical trials (RCT),30–34 and 1 SR with MA35 (Table 3). Back in 1988, Breuninger et al. published the first study that analyzed PMMS to treat BCC, finding a rate of recurrence <0.1% with a mean 4-year follow-up.19 One of the studies with the largest sample to date, >5200 patients, reported rates of recurrence <1% at 5 years.22 In a RCT that compared PMMS vs other techniques (including MMS), lower rates of recurrence with PMMS were found at 5 and 10 years, especially at 10 years in cases of recurrent tumors.31

Paraffin-embedded microscopically controlled surgery in basal cell carcinoma.

| Authors | Year | n | Description | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breuninger et al.19 | 1988 | 1,281 primary BCCs and 178 recurrent BCCs | Retrospective study.Single institution.Tübingen technique. | 6 recurrences during the follow-up period (4 primary tumors and 2 recurrent tumors). Mean follow-up of 4 years. |

| Holzschuh et al.22 | 1996 | >5,000 | Retrospective study.Single institution.Unspecified technique. | Recurrence rate <1% at 5 years. |

| der Plessis et al.24 | 1998 | 120 | Retrospective study.Single institution.Only periocular cases.Muffin technique. | Follow-up between 6 months and 5 years, without any recurrence |

| Smeets et al.30 | 2004 | 612 | Prospective randomized trial comparing MMS vs other modalities of excision for the treatment of BCC.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | Of primary BCCs, five (3%) recurred after conventional excision compared with three (2%) after PMMS during 30 months of follow-up.Of recurrent BCCs, three (3%) recurred after conventional excision and none after PMMS during 18 months of follow-up. |

| Mosterd et al.32 | 2008 | 612 | A prospective randomized controlled trial with 5-years’ follow-up.Quadrant method. | After five years, statistically significant differences in the recurrence rate for recurrent BCCs, not primary BCCs |

| Lawrence et al.13 | 2009 | 1,090 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | Recurrence rates of 2.8% at 5 years with MMS vs 0.7% with PMMS. |

| Morris et al.29 | 2009 | 278 | Prospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | Recurrence occurred in only one patient (0.58% of those with 5-year follow-up) |

| Häfner et al.27 | 2011 | 5,227 | Prospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 36 out of 3320 patients developed local recurrence Mean follow-up of 5 years. |

| Wollina et al.25 | 2014 | 321 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | No recurrences during follow-up (mean of 10 months). |

| van Loo et al.31 | 2014 | 612 | Prospective randomized controlled trial with 10-years’ follow-up.Unspecified technique. | After ten years of follow-up, a significant benefit for PMMS vs WLE was observed in primary BCC (4.4% vs 12.2%) and recurrent BCC (3.9% vs 13.5%) |

| Eberle et al.21 | 2014 | 947 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | At a median follow-up of 47 months, 10 of the 947 BCC recurred (1.1%). |

| Boehringer et al.33 | 2015 | 283 tumors (51.2%) in the MMS group; 270 tumors (48.8%) in the PMMS groups | Prospective randomized and blinded study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | For detection of tumor outgrowths, PMMS has almost twice the sensitivity of breadloaf microscopy, particularly in aggressive/infiltrative carcinomas. Recurrences rate was not determined. |

| Thornton et al.26 | 2019 | 169 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | 2.83% had recurred at 3 years. A smaller group of 72 patients survived and had a follow-up of 5 years, with a recurrence rate of 4.16%. |

| Kofler et al.34 | 2021 | 287 BCC in the PMMS and 282 BCC in the MMS group | Randomized, prospective and blinded study comparing PMMS vs MMS. Unicentric.Muffin and Tübingen techniques. | In the MMS group, re-excision was required in 21% of cases; 24 tumors (8.4%) recurred after a median of 2.2 years. In the PMMS group, re-excisions were required in 39% of cases; 10 tumors recurred (3.5%) after a median of 2.8 years. The recurrence rates differed significantly between both groups |

| Khaddaj et al.28 | 2021 | 407 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | Recurrence rate of 0.3%, median follow-up 36.3 months. |

| Kofler et al.23 | 2021 | 5,985 | Retrospective study with all tumors analyzed with PMMS.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 0.9% recurrences (1.7% in sclerodermiform BCC). Mean follow-up of 4 years. |

| Lacerda et al.35 | 2022 | 10,424 | SR and MA with eighteen studies were included, two RCTs and sixteen observational studies.Munich, Tübingen and Muffin techniques. | Global recurrence of 3.0% with MMS; 3.0% with the Munich technique; 1% with Tübingen technique and 0% with the Muffin technique. |

Abbreviations: BCC, basal cell carcinoma; MMS, Mohs micrographic surgery; PMMS, paraffin-embedded Mohs microscopically controlled surgery; RCT, randomized clinical trial; WLE, wide local excision; SR, systematic review; MA, meta-analysis.

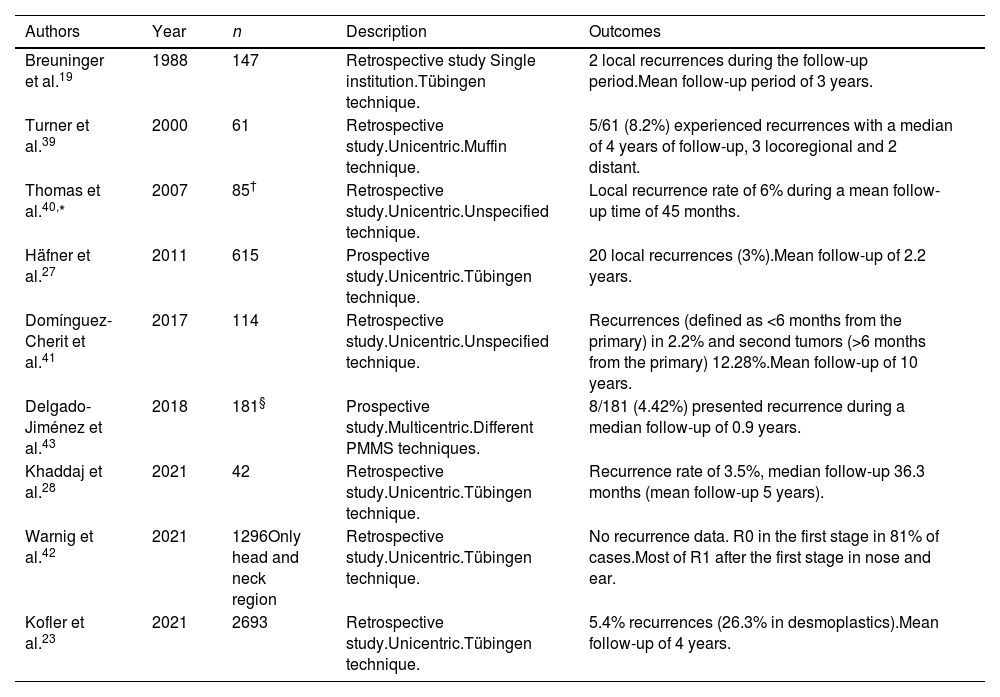

Generally, SCC prognosis is good, and surgical treatment is considered the standard of care.36 However, between 1% and 5% of the patients experience a more aggressive clinical course, especially if high-risk characteristics are added. MMS has been used successfully in several series of patients and seems to be the technique of choice ahead of PMMS. However, MMS can be associated with difficulties when processing the piecce.37,38 Our search found 9 studies of PMMS on the management of SCC in the scientific medical literature, 7 retrospective studies19,23,28,39–42 and 2 prospective studies27,43 (Table 4). In the first PMMS study on cSCC, Breuninger et al. described a rate of recurrence of 1.3% with a median 3-year follow-up.19 Later studies confirmed these results.19,23,27,28,39–43

Paraffin-embedded microscopically controlled surgery in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.

| Authors | Year | n | Description | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breuninger et al.19 | 1988 | 147 | Retrospective study Single institution.Tübingen technique. | 2 local recurrences during the follow-up period.Mean follow-up period of 3 years. |

| Turner et al.39 | 2000 | 61 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Muffin technique. | 5/61 (8.2%) experienced recurrences with a median of 4 years of follow-up, 3 locoregional and 2 distant. |

| Thomas et al.40,* | 2007 | 85† | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | Local recurrence rate of 6% during a mean follow-up time of 45 months. |

| Häfner et al.27 | 2011 | 615 | Prospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 20 local recurrences (3%).Mean follow-up of 2.2 years. |

| Domínguez-Cherit et al.41 | 2017 | 114 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | Recurrences (defined as <6 months from the primary) in 2.2% and second tumors (>6 months from the primary) 12.28%.Mean follow-up of 10 years. |

| Delgado-Jiménez et al.43 | 2018 | 181§ | Prospective study.Multicentric.Different PMMS techniques. | 8/181 (4.42%) presented recurrence during a median follow-up of 0.9 years. |

| Khaddaj et al.28 | 2021 | 42 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | Recurrence rate of 3.5%, median follow-up 36.3 months (mean follow-up 5 years). |

| Warnig et al.42 | 2021 | 1296Only head and neck region | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | No recurrence data. R0 in the first stage in 81% of cases.Most of R1 after the first stage in nose and ear. |

| Kofler et al.23 | 2021 | 2693 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 5.4% recurrences (26.3% in desmoplastics).Mean follow-up of 4 years. |

Abbreviations: MMS, Mohs micrographic surgery; PMMS, paraffin-embedded Mohs microscopically controlled surgery.

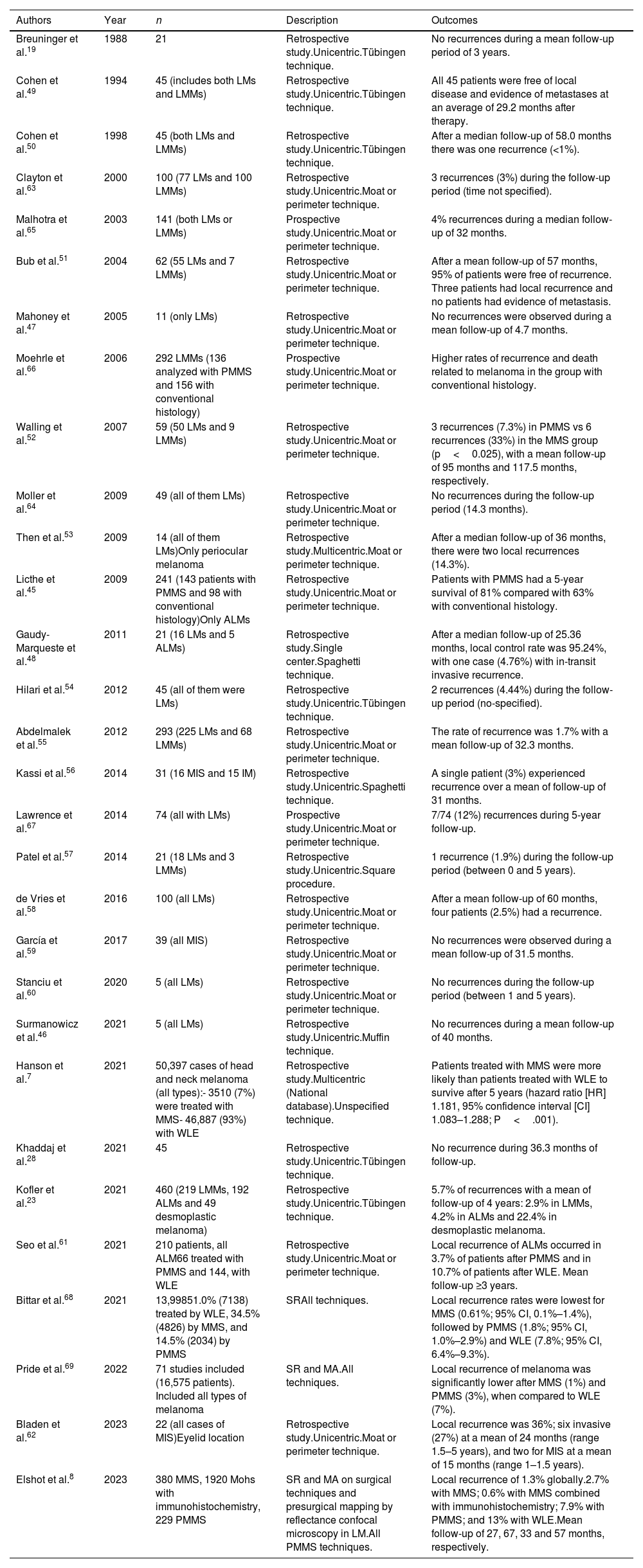

MMS has frequently been used for LM, LMM, and acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM). On many occasions, its use requires immunohistochemistry, either with frozen (MMS) or paraffin sections (PMMS).44,45 We found 30 studies with PMMS in melanoma (Table 5), 24 retrospective studies,7,19,23,28,45–64 3 prospective studies,65-67 1 SR,68 and 2 SR with MA.8,69 The first significant study dates back to 1988, when Breuninger et al.19 did not find any recurrences in 21 patients with LM. Subsequently, numerous studies with a larger number of patients ratified these results.7,8,13,23,28,45-62,64-66,68,69 In 2006, Moehrle et al. described lower rates of recurrence and death related to LMM in patients treated with PMMS vs conventional surgery.66 The study with the largest sample to date (Hanson et al.) (50,397 cases) demonstrated greater survival in patients treated with PMMS vs wide local excision (WLE).7 These results have also recently been published in cases of ALM.61 A recent SR and MA with >100 studies and 13,998 head and neck cutaneous melanomas found slightly higher recurrence rates in patients with PMMS vs MMS.68

Paraffin-embedded microscopically controlled surgery in melanoma and lentigo Maligna.

| Authors | Year | n | Description | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breuninger et al.19 | 1988 | 21 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | No recurrences during a mean follow-up period of 3 years. |

| Cohen et al.49 | 1994 | 45 (includes both LMs and LMMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | All 45 patients were free of local disease and evidence of metastases at an average of 29.2 months after therapy. |

| Cohen et al.50 | 1998 | 45 (both LMs and LMMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | After a median follow-up of 58.0 months there was one recurrence (<1%). |

| Clayton et al.63 | 2000 | 100 (77 LMs and 100 LMMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | 3 recurrences (3%) during the follow-up period (time not specified). |

| Malhotra et al.65 | 2003 | 141 (both LMs or LMMs) | Prospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | 4% recurrences during a median follow-up of 32 months. |

| Bub et al.51 | 2004 | 62 (55 LMs and 7 LMMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | After a mean follow-up of 57 months, 95% of patients were free of recurrence. Three patients had local recurrence and no patients had evidence of metastasis. |

| Mahoney et al.47 | 2005 | 11 (only LMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | No recurrences were observed during a mean follow-up of 4.7 months. |

| Moehrle et al.66 | 2006 | 292 LMMs (136 analyzed with PMMS and 156 with conventional histology) | Prospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | Higher rates of recurrence and death related to melanoma in the group with conventional histology. |

| Walling et al.52 | 2007 | 59 (50 LMs and 9 LMMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | 3 recurrences (7.3%) in PMMS vs 6 recurrences (33%) in the MMS group (p<0.025), with a mean follow-up of 95 months and 117.5 months, respectively. |

| Moller et al.64 | 2009 | 49 (all of them LMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | No recurrences during the follow-up period (14.3 months). |

| Then et al.53 | 2009 | 14 (all of them LMs)Only periocular melanoma | Retrospective study.Multicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | After a median follow-up of 36 months, there were two local recurrences (14.3%). |

| Licthe et al.45 | 2009 | 241 (143 patients with PMMS and 98 with conventional histology)Only ALMs | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | Patients with PMMS had a 5-year survival of 81% compared with 63% with conventional histology. |

| Gaudy-Marqueste et al.48 | 2011 | 21 (16 LMs and 5 ALMs) | Retrospective study.Single center.Spaghetti technique. | After a median follow-up of 25.36 months, local control rate was 95.24%, with one case (4.76%) with in-transit invasive recurrence. |

| Hilari et al.54 | 2012 | 45 (all of them were LMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 2 recurrences (4.44%) during the follow-up period (no-specified). |

| Abdelmalek et al.55 | 2012 | 293 (225 LMs and 68 LMMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | The rate of recurrence was 1.7% with a mean follow-up of 32.3 months. |

| Kassi et al.56 | 2014 | 31 (16 MIS and 15 IM) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Spaghetti technique. | A single patient (3%) experienced recurrence over a mean of follow-up of 31 months. |

| Lawrence et al.67 | 2014 | 74 (all with LMs) | Prospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | 7/74 (12%) recurrences during 5-year follow-up. |

| Patel et al.57 | 2014 | 21 (18 LMs and 3 LMMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Square procedure. | 1 recurrence (1.9%) during the follow-up period (between 0 and 5 years). |

| de Vries et al.58 | 2016 | 100 (all LMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | After a mean follow-up of 60 months, four patients (2.5%) had a recurrence. |

| García et al.59 | 2017 | 39 (all MIS) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | No recurrences were observed during a mean follow-up of 31.5 months. |

| Stanciu et al.60 | 2020 | 5 (all LMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | No recurrences during the follow-up period (between 1 and 5 years). |

| Surmanowicz et al.46 | 2021 | 5 (all LMs) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Muffin technique. | No recurrences during a mean follow-up of 40 months. |

| Hanson et al.7 | 2021 | 50,397 cases of head and neck melanoma (all types):- 3510 (7%) were treated with MMS- 46,887 (93%) with WLE | Retrospective study.Multicentric (National database).Unspecified technique. | Patients treated with MMS were more likely than patients treated with WLE to survive after 5 years (hazard ratio [HR] 1.181, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.083–1.288; P<.001). |

| Khaddaj et al.28 | 2021 | 45 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | No recurrence during 36.3 months of follow-up. |

| Kofler et al.23 | 2021 | 460 (219 LMMs, 192 ALMs and 49 desmoplastic melanoma) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 5.7% of recurrences with a mean of follow-up of 4 years: 2.9% in LMMs, 4.2% in ALMs and 22.4% in desmoplastic melanoma. |

| Seo et al.61 | 2021 | 210 patients, all ALM66 treated with PMMS and 144, with WLE | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | Local recurrence of ALMs occurred in 3.7% of patients after PMMS and in 10.7% of patients after WLE. Mean follow-up ≥3 years. |

| Bittar et al.68 | 2021 | 13,99851.0% (7138) treated by WLE, 34.5% (4826) by MMS, and 14.5% (2034) by PMMS | SRAll techniques. | Local recurrence rates were lowest for MMS (0.61%; 95% CI, 0.1%–1.4%), followed by PMMS (1.8%; 95% CI, 1.0%–2.9%) and WLE (7.8%; 95% CI, 6.4%–9.3%). |

| Pride et al.69 | 2022 | 71 studies included (16,575 patients). Included all types of melanoma | SR and MA.All techniques. | Local recurrence of melanoma was significantly lower after MMS (1%) and PMMS (3%), when compared to WLE (7%). |

| Bladen et al.62 | 2023 | 22 (all cases of MIS)Eyelid location | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | Local recurrence was 36%; six invasive (27%) at a mean of 24 months (range 1.5–5 years), and two for MIS at a mean of 15 months (range 1–1.5 years). |

| Elshot et al.8 | 2023 | 380 MMS, 1920 Mohs with immunohistochemistry, 229 PMMS | SR and MA on surgical techniques and presurgical mapping by reflectance confocal microscopy in LM.All PMMS techniques. | Local recurrence of 1.3% globally.2.7% with MMS; 0.6% with MMS combined with immunohistochemistry; 7.9% with PMMS; and 13% with WLE.Mean follow-up of 27, 67, 33 and 57 months, respectively. |

Abbreviations: MMS, Mohs micrographic surgery; PMMS, paraffin-embedded Mohs microscopically controlled surgery; LM: lentigo maligna; LMM, lentigo maligna melanoma; ALM, acral lentiginous melanoma; MIS, melanoma in situ; IM, invasive melanoma; SD, standard deviation; WLE, wide local excision.

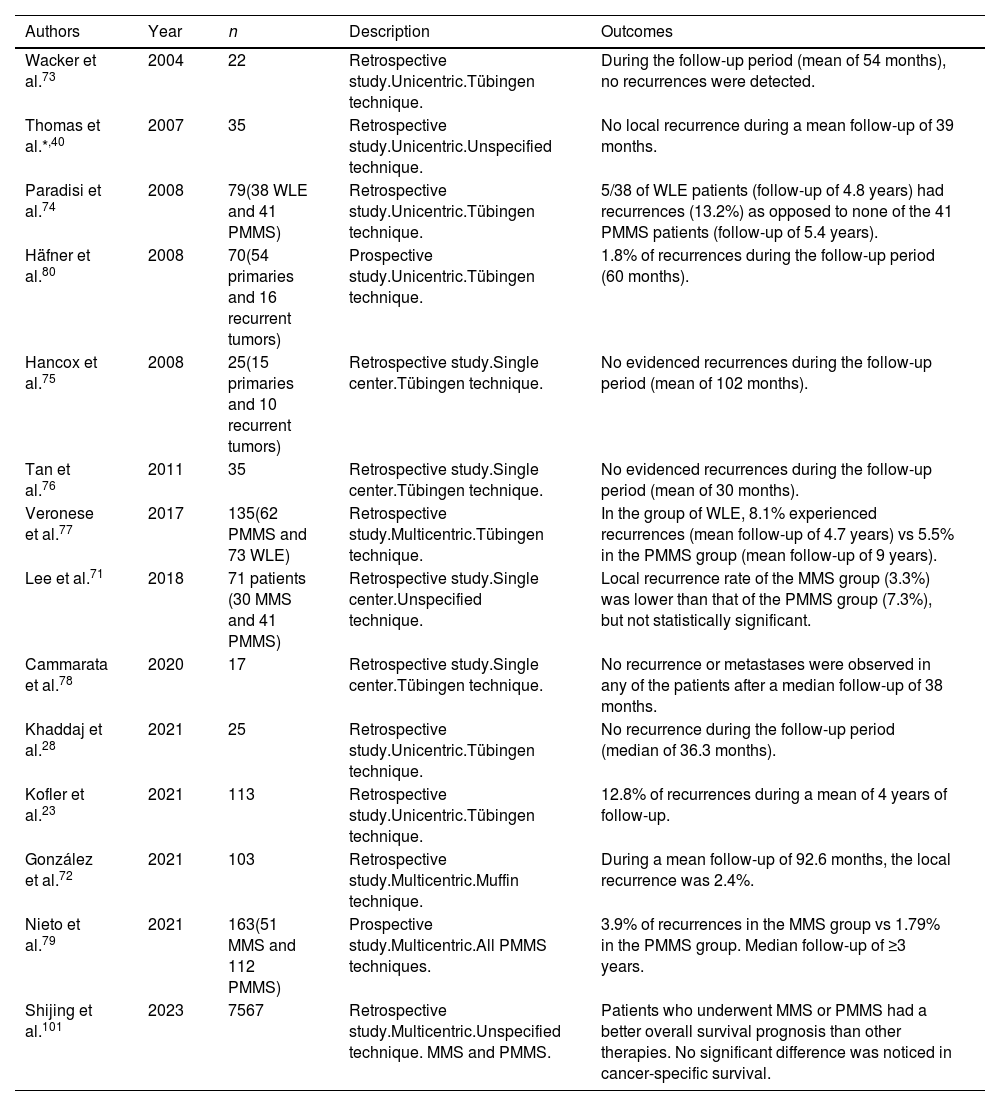

In terms of less recurrence, MMS has proven superior to WLE to treat dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP).70 In fact, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines now recommend MMS as the preferred approach for DFSP. Same as it happens with LM, LMM and ALM, due to the difficulty of studying them in frozen sections, PMMS is generally used for DFSP. We found 14 studies of PMMS for DFSP, 12 retrospective studies23,28,40,71-78 and 2 prospective studies79,80 (Table 6).

Paraffin-embedded microscopically controlled surgery in dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans.

| Authors | Year | n | Description | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wacker et al.73 | 2004 | 22 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | During the follow-up period (mean of 54 months), no recurrences were detected. |

| Thomas et al.*,40 | 2007 | 35 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | No local recurrence during a mean follow-up of 39 months. |

| Paradisi et al.74 | 2008 | 79(38 WLE and 41 PMMS) | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 5/38 of WLE patients (follow-up of 4.8 years) had recurrences (13.2%) as opposed to none of the 41 PMMS patients (follow-up of 5.4 years). |

| Häfner et al.80 | 2008 | 70(54 primaries and 16 recurrent tumors) | Prospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 1.8% of recurrences during the follow-up period (60 months). |

| Hancox et al.75 | 2008 | 25(15 primaries and 10 recurrent tumors) | Retrospective study.Single center.Tübingen technique. | No evidenced recurrences during the follow-up period (mean of 102 months). |

| Tan et al.76 | 2011 | 35 | Retrospective study.Single center.Tübingen technique. | No evidenced recurrences during the follow-up period (mean of 30 months). |

| Veronese et al.77 | 2017 | 135(62 PMMS and 73 WLE) | Retrospective study.Multicentric.Tübingen technique. | In the group of WLE, 8.1% experienced recurrences (mean follow-up of 4.7 years) vs 5.5% in the PMMS group (mean follow-up of 9 years). |

| Lee et al.71 | 2018 | 71 patients (30 MMS and 41 PMMS) | Retrospective study.Single center.Unspecified technique. | Local recurrence rate of the MMS group (3.3%) was lower than that of the PMMS group (7.3%), but not statistically significant. |

| Cammarata et al.78 | 2020 | 17 | Retrospective study.Single center.Tübingen technique. | No recurrence or metastases were observed in any of the patients after a median follow-up of 38 months. |

| Khaddaj et al.28 | 2021 | 25 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | No recurrence during the follow-up period (median of 36.3 months). |

| Kofler et al.23 | 2021 | 113 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 12.8% of recurrences during a mean of 4 years of follow-up. |

| González et al.72 | 2021 | 103 | Retrospective study.Multicentric.Muffin technique. | During a mean follow-up of 92.6 months, the local recurrence was 2.4%. |

| Nieto et al.79 | 2021 | 163(51 MMS and 112 PMMS) | Prospective study.Multicentric.All PMMS techniques. | 3.9% of recurrences in the MMS group vs 1.79% in the PMMS group. Median follow-up of ≥3 years. |

| Shijing et al.101 | 2023 | 7567 | Retrospective study.Multicentric.Unspecified technique. MMS and PMMS. | Patients who underwent MMS or PMMS had a better overall survival prognosis than other therapies. No significant difference was noticed in cancer-specific survival. |

Abbreviations: MMS: Mohs micrographic surgery; PMMS, paraffin-embedded microscopically controlled surgery.

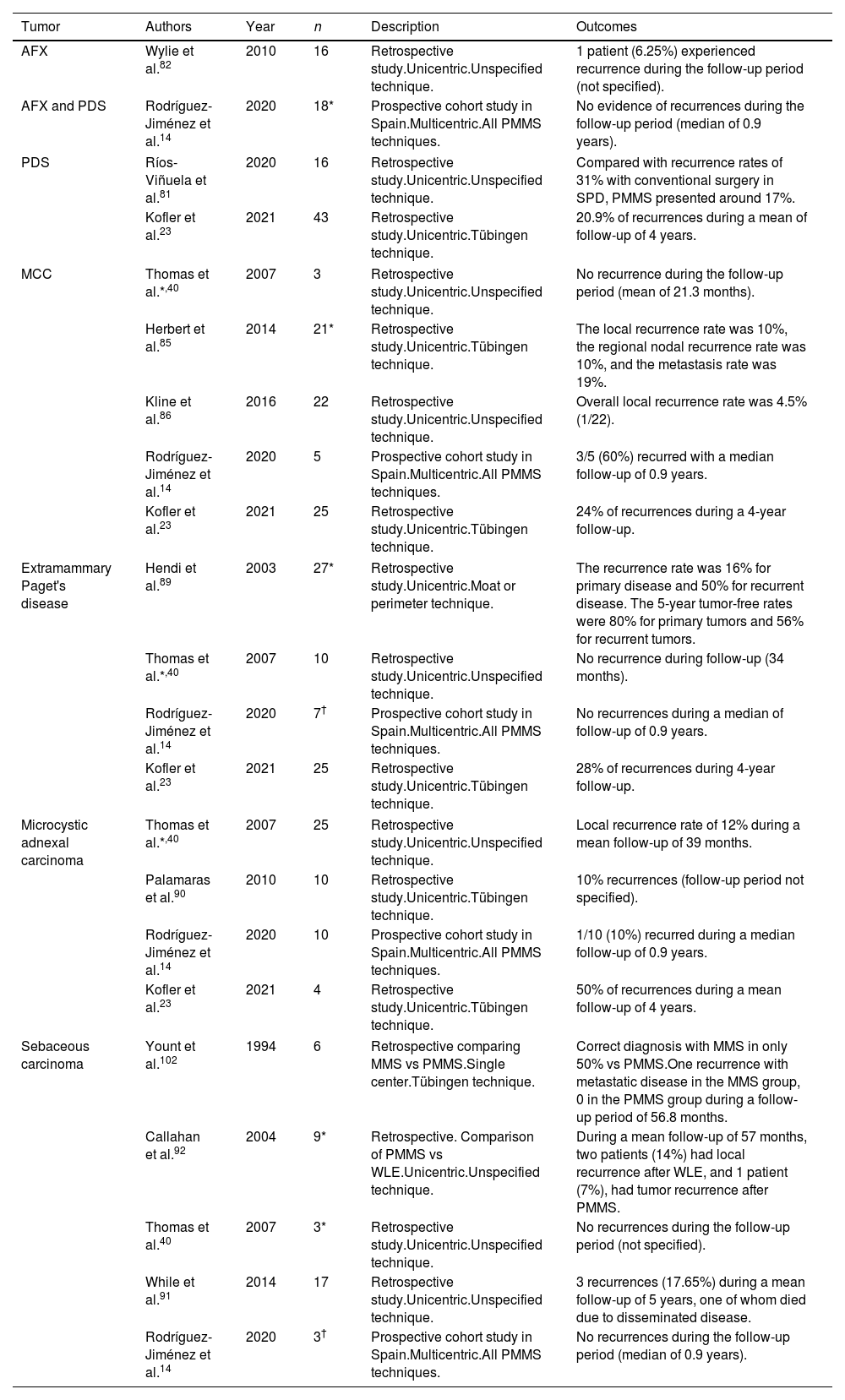

MMS has proven to lower the rate of recurrence vs WLE in the management of AFX and (although less defined in the literature) in the management of pleomorphic dermal sarcoma (PDS), and tumors with different characteristics and prognoses, but most probably within the same spectrum.4,81 Few large series (>5 patients) have investigated PMMS with these malignancies (Table 7). Our search found 3 retrospective studies23,81,82 and 1 prospective study.14 In these investigations, low rates of recurrence were found for AFX, but were higher for PDS.14,23,81,82

Paraffin-embedded microscopically controlled surgery in infrequent tumors.

| Tumor | Authors | Year | n | Description | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFX | Wylie et al.82 | 2010 | 16 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | 1 patient (6.25%) experienced recurrence during the follow-up period (not specified). |

| AFX and PDS | Rodríguez-Jiménez et al.14 | 2020 | 18* | Prospective cohort study in Spain.Multicentric.All PMMS techniques. | No evidence of recurrences during the follow-up period (median of 0.9 years). |

| PDS | Ríos-Viñuela et al.81 | 2020 | 16 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | Compared with recurrence rates of 31% with conventional surgery in SPD, PMMS presented around 17%. |

| Kofler et al.23 | 2021 | 43 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 20.9% of recurrences during a mean of follow-up of 4 years. | |

| MCC | Thomas et al.*,40 | 2007 | 3 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | No recurrence during the follow-up period (mean of 21.3 months). |

| Herbert et al.85 | 2014 | 21* | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | The local recurrence rate was 10%, the regional nodal recurrence rate was 10%, and the metastasis rate was 19%. | |

| Kline et al.86 | 2016 | 22 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | Overall local recurrence rate was 4.5% (1/22). | |

| Rodríguez-Jiménez et al.14 | 2020 | 5 | Prospective cohort study in Spain.Multicentric.All PMMS techniques. | 3/5 (60%) recurred with a median follow-up of 0.9 years. | |

| Kofler et al.23 | 2021 | 25 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 24% of recurrences during a 4-year follow-up. | |

| Extramammary Paget's disease | Hendi et al.89 | 2003 | 27* | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Moat or perimeter technique. | The recurrence rate was 16% for primary disease and 50% for recurrent disease. The 5-year tumor-free rates were 80% for primary tumors and 56% for recurrent tumors. |

| Thomas et al.*,40 | 2007 | 10 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | No recurrence during follow-up (34 months). | |

| Rodríguez-Jiménez et al.14 | 2020 | 7† | Prospective cohort study in Spain.Multicentric.All PMMS techniques. | No recurrences during a median of follow-up of 0.9 years. | |

| Kofler et al.23 | 2021 | 25 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 28% of recurrences during 4-year follow-up. | |

| Microcystic adnexal carcinoma | Thomas et al.*,40 | 2007 | 25 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | Local recurrence rate of 12% during a mean follow-up of 39 months. |

| Palamaras et al.90 | 2010 | 10 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 10% recurrences (follow-up period not specified). | |

| Rodríguez-Jiménez et al.14 | 2020 | 10 | Prospective cohort study in Spain.Multicentric.All PMMS techniques. | 1/10 (10%) recurred during a median follow-up of 0.9 years. | |

| Kofler et al.23 | 2021 | 4 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Tübingen technique. | 50% of recurrences during a mean follow-up of 4 years. | |

| Sebaceous carcinoma | Yount et al.102 | 1994 | 6 | Retrospective comparing MMS vs PMMS.Single center.Tübingen technique. | Correct diagnosis with MMS in only 50% vs PMMS.One recurrence with metastatic disease in the MMS group, 0 in the PMMS group during a follow-up period of 56.8 months. |

| Callahan et al.92 | 2004 | 9* | Retrospective. Comparison of PMMS vs WLE.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | During a mean follow-up of 57 months, two patients (14%) had local recurrence after WLE, and 1 patient (7%), had tumor recurrence after PMMS. | |

| Thomas et al.40 | 2007 | 3* | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | No recurrences during the follow-up period (not specified). | |

| While et al.91 | 2014 | 17 | Retrospective study.Unicentric.Unspecified technique. | 3 recurrences (17.65%) during a mean follow-up of 5 years, one of whom died due to disseminated disease. | |

| Rodríguez-Jiménez et al.14 | 2020 | 3† | Prospective cohort study in Spain.Multicentric.All PMMS techniques. | No recurrences during the follow-up period (median of 0.9 years). | |

Abbreviations: MMS, Mohs micrographic surgery; PMMS, paraffin-embedded microscopically controlled surgery; AFX, atypical fibroxanthoma; PDS, plemorphic dermal sarcoma.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is one of the most aggressive tumors in dermato-oncology. There are a few studies that evaluate MMS for this tumor. Recent studies have studied the non-inferiority of MMS over WLE, however, patients treated with MMS were less likely to undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy.83,84 We found 5 studies on PMMS for MCC: 4 retrospective studies23,85–87 and 1 prospective study.14 They are summarized in Table 7.14,23,40,85,86 The series with the largest number of patients (n=22) treated with PMMS reported a rate of recurrence <5%.86

Extramammary Paget's diseaseExtramammary Paget's disease tends to spread intraepidermally with multiple clinically poorly defined foci. Lower rates of recurrence have recently been shown with MMS.88 We found 4 studies of PMMS for extramammary Paget's disease (Table 7): 3 retrospective studies23,40,89 and 1 prospective study.14 The study with the largest sample (n=25)23 showed a rate of recurrence of 28% during a mean 4-year follow-up.

Microcystic adnexal carcinomaMicrocystic adnexal carcinoma is a very rare tumor with local and even distant invasive capacity. Our search found 4 studies on PMMS to treat microcystic adnexal carcinoma: 3 retrospective studies23,40,90 and 1 prospective study.14 There are no studies comparing MMS to PMMS. In the PMMS group, the data series report rates of recurrence between 0% and 30% at a nearly 5-year follow-up (Table 7).

Sebaceous carcinomaStudies on MMS in sebaceous carcinoma are scarce. Recent studies have shown a lower rate of recurrence, but without improved survival, at 5 and 10 years with MMS. Our search resulted in 5 studies on PMMS in sebaceous carcinoma: 4 retrospective studies34,40,91,92 and 1 prospective study.14 The study with the largest sample size (n=17) reported 3 recurrences (17.65%) at a mean 5-year follow-up91 (Table 7).

DiscussionMMS is an effective treatment variant for numerous cutaneous malignancies. It has achieved significant superiority vs WLE to treat recurrent and high-risk non-melanoma skin cancer.93 However, multiple difficulties need to be overcome to perform MMS, and PMMS can be easier to implement, and has significant advantages.16 Histopathological examinations may differ when comparing frozen vs paraffin sections. In a classic study of 258 samples analyzed in both ways, it was found that the initial biopsy diagnosis differed from the Mohs frozen and paraffin section diagnoses in 20% of the cases.94 We should mention that, although both conventional MMS and PMMS theoretically analyze 100% of the margins, in actuality, on numerous occasions they give “false negatives” in frozen sections, caused by the lower tissue quality of these sections. On the contrary, paraffin sections tend to offer better tissue quality, allowing small tumor remains to be analyzed, and reducing the rates of false negatives.16,20,95 Regarding its effectiveness, PMMS has shown a lower rate of recurrence vs MMS in the management of BCC in RCTs.31,33,34 In the case of cSCC, no studies have ever compared MMS to PMMS. However, a recent study stated that in 27.8% of the re-examined cSCC treated with MMS reporting free margins, sections tumor outgrowths were still visible in immunohistochemistry that had not been detected via HE staining. Therefore, PMMS could play a fundamental role through deferred immunohistochemistry, and in the detection of atypical patterns.16,94 PMMS has shown rates of recurrence ranging from 3% to 10% at 5 years.19,23,27,28,39-41,43 Frozen sections of MMS are generally insufficient to analyze melanocytic tumors,87 and PMMS has shown lower rates of relapse in LM and LMM vs WLE.68 Regarding survival, although some studies did not show an increased overall survival rate with MMS and PMMS vs WLE in the management of LM and LMM,96 recent studies have revealed a greater overall survival in patients treated with PMMS vs WLE, especially on the head and scalp.7,97 Regarding infrequent tumors such as DFSP, lower rates of recurrence have been reported with PMMS vs MMS.72 However, data in primary cases found no difference in overall survival for patients treated with WLE vs PMMS.98 As for MCC, it has not been possible to demonstrate that PMMS presents a lower rate of recurrence or better survival than MMS,14,23,40,85,86 but may allow narrower margins, and fewer functional and esthetic complications. Given the difficulty of in vivo examination and the possibility of failure in the analysis of rare tumors, PMMS has been proposed as the technique of choice for excision of AFX, PDS, extramammary Paget's disease and sebaceous carcinoma, among others. However, most of the data found in the literature allude to small series.

Regarding the disadvantages of PMMS, the need for several surgical sessions and the possibility of architectural changes of the piece due to repeated suture threads stand out.99 However, immediate closure is possible. This can be performed using skin grafting or biomembranes, secondary intention healing or primary closure, among other techniques that do not produce significant anatomical distortions.16 In these cases, we recommend taking pictures of the surgical defect before and after reconstruction to achieve an exact topographic correlation if a positive margin is found. In any case, complex reconstructions are ill-advised until all margins are reported to be tumor-free. Although PMMS can require surgical interventions to be performed on different days, which could increase costs, the decrease in recurrences vs other techniques and, therefore, the need for large secondary surgeries, along with functional and cosmetic complications, could, in the long run, be more cost effective: studies on the cost effectiveness of PMMS are required. When performing PMMS, a good and fluent communication between the dermatologist and the pathologist is essential, to avoid long waiting times that may increase the patient's anxiety while waiting for the histopathological results. In our hospital, we have extensive experience performing both MMS and PMMS, and sometimes we even combine these techniques during resection of a complex or large tumor, or in specific anatomical areas.

We should mention that in a recent study no major postoperative complications were found with PMMS vs MMS.100

LimitationsThe present literature review is limited by the fact that it is a narrative review and not a SR of the scientific medical literature currently available, or a MA. Similarly, many of the studies included have small or medium sized samples, a retrospective design, heterogeneous methodologies, or use different surgical techniques. Additionally, the terminology of MMS vs PMMS is, sometimes, controversial in the literature, with both terms overlapping in numerous articles. These factors make it difficult to extrapolate or generalize our findings.

ConclusionsComplete resection with free surgical margins is the gold standard in the management of skin cancer. PMMS requires minimal training for the dermatologic surgeon, the pathology technician, and the pathologist. PMMS does not require special equipment either, and can be very useful and effective to treat diverse skin neoplasms, both frequent tumors such as BCC, SCC, or LMM, and rare neoplasms such as DFSP or AFX, among others. PMMS techniques also allow better analysis of tumor remains than MMS and could reduce the rate of false negative. We want to emphasize that it can be adopted even in small hospitals or clinics and significantly reduce the risk of incomplete tumor resection, and/or local recurrence.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

We wish to thank Elena Morgado for the images provided for this article.