Genital herpes is a sexually transmitted disease with a high global prevalence mainly caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2, although there has been an increase in the number of cases caused by HSV-1 in recent years.1–3 Co-infection by HSV is common in patients with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The atypical clinical presentations of HSV infection are rare, but they are now more frequent in clinical practice, due to the increasing number of immunosuppressed patients. HSV infection can cause hypertrophic, verrucous, or nodular lesions, sometimes ulcerated on its surface.3–5 In a series of patients with genital herpes, the estimated prevalence of hypertrophic presentations was 4.8%, most frequent in HIV-infected patients.5 Therapy in individuals with atypical presentations is complex, particularly in the presence of HIV seropositivity, requiring longer treatment time and being associated with significant resistance to antiviral drugs used.3–5

We report a case of a 51-years-old Western African man with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) referred to our Dermatology Department with painful perianal verrucous nodules and plaques for two months (Fig. 1). HIV infection was diagnosed four years previously, and antiretroviral therapy with lopinavir, ritonavir, emtricitabine and tenofovir had been erratically taken. CD4+ T lymphocyte count and viral load were 72cell/mm3 and 436,000copies per milliliter, respectively. A squamous cell carcinoma was suspected, but skin biopsy was suggestive of herpetic infection (Fig. 2), and sequencing by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of the exudate was positive to HSV-2. The antiretroviral therapy was restarted, and it was also initiated intravenous acyclovir (10mg/kg) simultaneously for one week and then valacyclovir 1g 8/8h. Despite the rise of CD4+ T lymphocytes and an initial clinical improvement, there was an unsatisfactory response to valacyclovir at the third month, so topical 5% imiquimod was started three times weekly in addition. A significant clinical response after three weeks was evident with lesions regression (Fig. 3) and resolution of pain. Local irritation was the only side effect reported. The patient stood on prophylactic antiviral therapy, but three months later, he had a stroke and was lost to follow up.

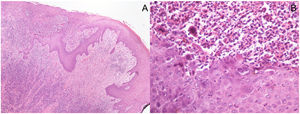

Histopathological pictures: (A) Punch biopsy of superficially ulcerated skin sample showing epidermal necrosis overlying a superficial and deep dense perivascular and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis. No malignant cells are seen. (Hematoxylin/eosin ×40). (B) Higher magnification highlights viral cytopathic changes, namely vacuolization of keratinocytes (ballooning), multinucleated keratinocytes with eosinophilic cytoplasm, margination of nuclear chromatin and eosinophilic internuclear inclusions (Cowdry type A). The inflammatory infiltrate is predominantly lymphocytic, with admixed plasma cells, neutrophils and scattered eosinophils. (Hematoxylin/eosin ×400).

The origin of hypertrophic lesions in HSV infection seems to be a process of immune dysregulation mediated by cytokines produced by T helper type 2 lymphocytes, which promotes hyperplasia of the epidermis. This phenomenon is independent of the stage of HIV infection and can be observed in individuals with normal CD4+ lymphocyte counts or in the presence or absence of antiretroviral therapy. There are also described cases in the inflammatory syndrome of immune reconstitution, probably also associated with an inappropriate immune response.6

The diagnosis of hypertrophic herpetic infection requires both clinical and histopathological data, with viral culture, PCR and/or immunohistochemistry.4 The histopathological examination is important for differential diagnosis between these hypertrophic lesions and squamous cell carcinoma. The suspicion for a malignant tumor increases in the presence of an exophytic mass of large rapid growth, with ulceration or associated lymphadenopathy. Sometimes, the two diagnoses co-exist, with tumoral tissue foci being identified in a substrate of hypertrophic herpetic lesion.7,8 Other differential diagnoses include Buschke's Lowenstein tumor, condylomata lata, co-infection with herpes zoster virus or cytomegalovirus, and giant molluscum contagiosum.3

The hypertrophic lesions are often refractory to first-line systemic antiviral agents, like acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir. The resistance rate varies from 5% to 7% according to the series and in the presence of a recalcitrant herpetic lesion, pharmacological resistance should be presumed, and a viral culture performed.2 However, it is not available in most hospitals. Foscarnet and cidofovir have been used, with variable outcomes.2,9,10 Topical imiquimod therapy is a safe alternative for recurrent and/or refractory herpetic lesions to antiviral therapy. This drug is an agonist of the Toll-like receptor, mechanism through which it stimulates the cell-mediated immune response.10 Its immunomodulatory effects make it an important therapeutic strategy in the presence of atypical herpetic lesions in individuals with high risk of developing drug resistance. In most of the cases described, a dose of 5% imiquimod was administrated three times a week, with a reported cure of skin lesions between one and 14 weeks.9–11 Combination therapy with topical imiquimod and a single antiviral administration is another alternative, which showed promising results in hypertrophic lesions non-responsive to antivirals alone.5,9–11 Other therapeutic options reported as effective in refractory hypertrophic herpetic lesions include thalidomide, gamma interferon (IFN-γ), and surgical excision.9,10 The recurrence rate in these patients is, nevertheless, high, and after lesion resolution, prophylactic antiviral therapy is recommended.2

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.