Livedoid vasculopathy is a chronic thrombo-occlusive disease with significant skin involvement.1 Due to its chronic nature, it poses a therapeutic challenge. Various treatment options have demonstrated their beneficial role in multiple studies.2,3 However, refractory cases can sometimes be difficult to manage, making the search for new therapeutic modalities relevant for disease control and symptomatic relief for patients.

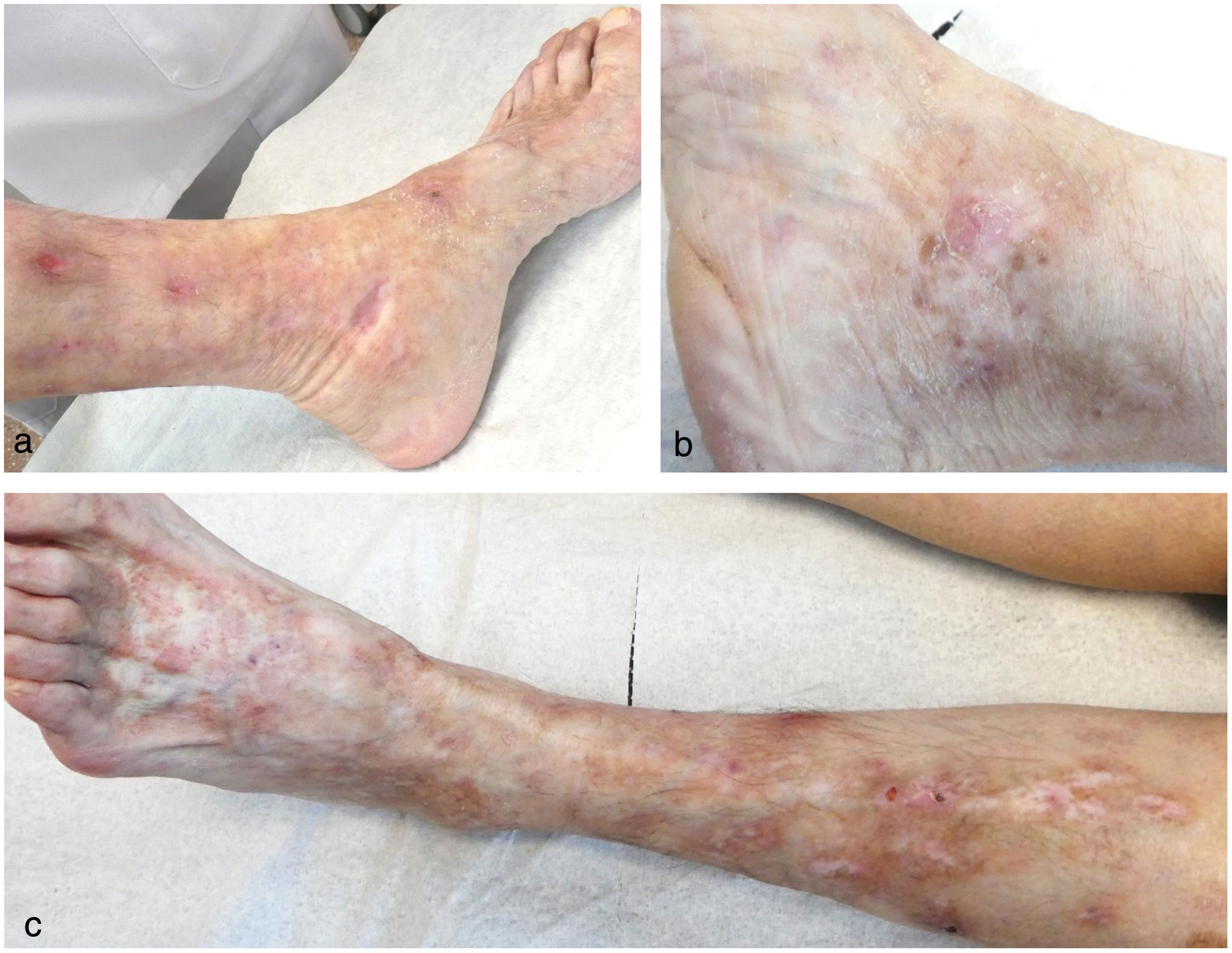

This is the case of a 68-year-old woman under dermatological supervision with a 6-year history of lesion outbreaks on her legs that, both clinically and histologically, were consistent with livedoid vasculopathy (Fig. 1). Tests performed to rule out any associated disease, such as antiphospholipid syndrome, paraproteinemias, genetic prothrombotic disorders, rheumatologic and autoimmune diseases tested negative. The patient received multiple topical, oral, and parenteral drugs (pentoxifylline, acetylsalicylic acid, colchicine, nifedipine, bosentan, rivaroxaban, sildenafil, nitroglycerin, immunoglobulins, rituximab, and sevoflurane), which were eventually discontinued due to lack of response or intolerance. Additionally, she exhibited poor tolerance to different analgesics. Given the torpid and aggressive course of the condition, poor pain control, and skin involvement, she was referred to the Pain Unit, where she underwent spinal cord posterior column stimulation implant placement. The patient showed a marked improvement in pain and almost complete resolution of the cutaneous ulcers, with a sustained response over the following months (Fig. 2).

Livedoid vasculopathy is a rare chronic skin disorder that impacts quality of life significantly. Clinical presentation is characterized by persistent, very painful ulcers that mainly affect the legs bilaterally. Additionally, patients display livedo racemosa and areas of atrophie blanche.1 Diagnosis is histologically confirmed, including the presence of intraluminal thrombosis, endothelial proliferation, and subintimal hyaline degeneration of the dermal vasculature.4 After histopathological confirmation, associated systemic diseases such as primary antiphospholipid syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic sclerosis, or mixed connective tissue disease should be ruled out.5

Various treatment modalities often yield inconsistent results, requiring combined or sequential procedures, typically with low levels of evidence.2,3 On the one hand, it is important to implement general measures such as pain management, wound care, and compression therapy.3,4 On the other hand, therapeutic measures aimed at reducing the risk of thrombosis, such as antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, and fibrinolytic agents, as well as immunomodulators and vasodilators, are used.3

The implantation of electrodes over the posterior spinal columns works through 2 mechanisms: centripetal inhibition, preventing the nerve impulse from the peripheral nerve endings to the central nervous system, which stops the pain sensation from becoming conscious; and centrifugal inhibition, preventing the creation of a sympathetic nerve impulse, promoting peripheral vasodilation and improving perfusion of distal areas, and reducing pain.6,7 In our patient, this translated into a satisfactory improvement of the ulcers and discomfort intensity. Its use in other vasculopathies has been documented in the literature, yet no cases of livedoid vasculopathy successfully treated with this modality have ever been published to this date.8 This technique is fairly safe, with complication incidence rates of 5.3% up to 40%.9 Among them, we find surgical infections7,9 (2.5% up to 10%9) and mechanical complications such as migration (2.1% up to 27%9) or breakage (0% up to 9.1%) of the wire, discomfort caused by the pulse generator (0.9-12%7,9), and device malfunction (0% up to 10.2%9). The most serious complication is neurological damage (0.4% up to 2.1%10), which may include the development of epidural hematoma (0.3%), major neurological deficit (0.25%), limited motor deficit (0.1%), autonomic changes (0.013%), or sensory deficit (0.1%).9 However, these rates have dropped due to technological advancements and improved implantation techniques.9

The formation of an epidural hematoma is rare, primarily occurring after surgical device insertion, and sometimes resulting in permanent neurological damage. This risk is increased in patients on antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy, so clinical practice guidelines exist to prevent it. Since the incidence of epidural hematomas in patients on anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy is unknown, management must be individualized.10

Posterior column stimulation can be considered an alternative when treating patients with livedoid vasculopathy who remain unresponsive to other more traditional options.