This is the case of a 32-year-old man with an 8-year history of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who was admitted for his 3rd allogeneic bone marrow transplant (BMT). Two weeks after hospitalization, the patient developed febrile neutropenia and respiratory symptoms, despite being on prophylactic treatment with levofloxacin, amikacin, posaconazole, and acyclovir. A thoracic computerized tomography (CT) scan confirmed the presence of three nodular lesions in the right upper lobe, which led to adding isavuconazole and amphotericin B to the antimicrobial regimen. On day +42 after BMT, the patient presented with progressively spreading erythematous papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities, some with blisters, and a central crust (Fig. 1). Two palpable and painful subcutaneous nodules were also noted on the left thigh.

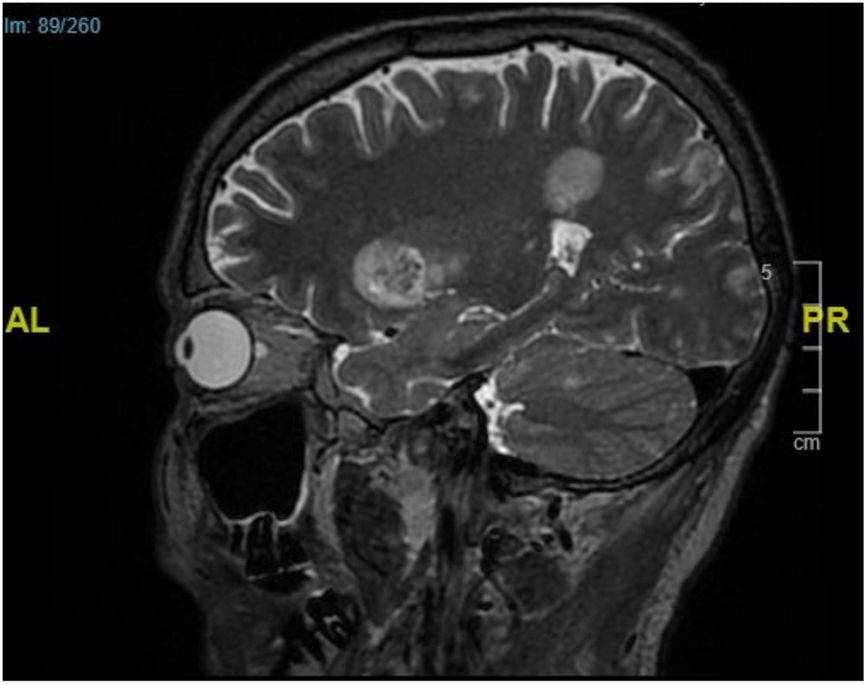

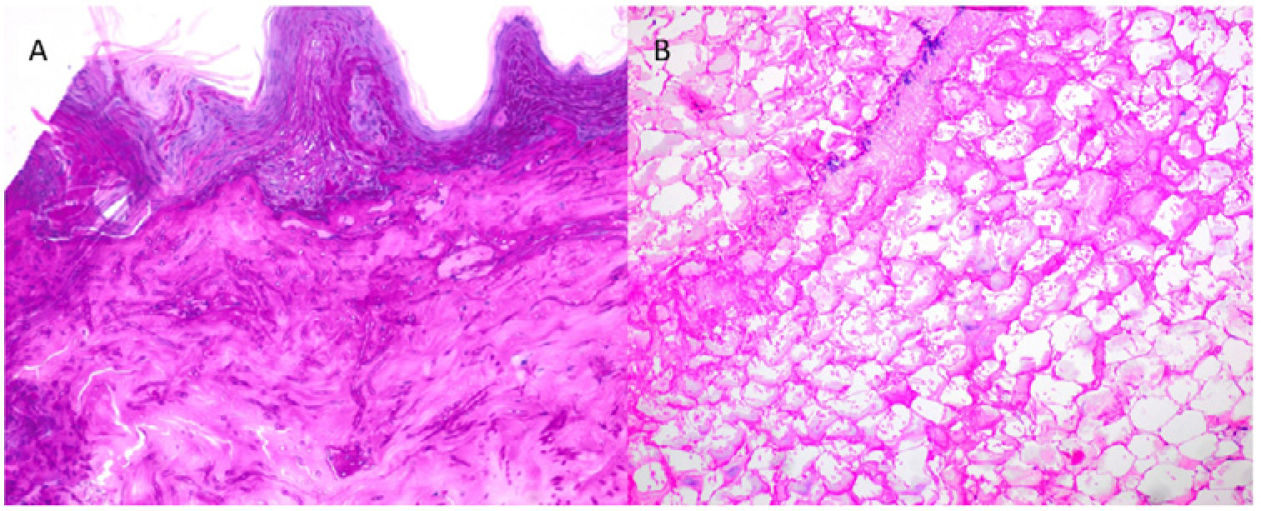

Supplementary testsTwo skin biopsies were performed on a plaque and a subcutaneous nodule. Histopathology examination confirmed a substantial presence of elongated and septate hyphae across the dermis and epidermis and up to the stratum corneum (Fig. 2A). Extensive panniculitis-like fat necrosis and hyphae inside the adipose tissue were also noted (Fig. 2B). Before mycological confirmation, the patient became obtunded. The emergency CT scan of the brain revealed the presence of parenchymal lesions consistent with septic emboli. Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (Fig. 3) confirmed the findings.

What is your diagnosis?

DiagnosisCutaneous disseminated aspergillosis.

Course of the disease and treatmentThe molecular analysis of the sample confirmed the presence of Aspergillus alliaceus as the causative pathogen. Unfortunately, despite treatment, the patient died 48h later.

CommentAspergillosis is one of the most frequent opportunistic mycoses in patients with hematologic malignancies and neutropenia, particularly those undergoing BNT for AML. Predominant isolated pathogens include Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus flavus. Cutaneous aspergillosis only accounts for 4% of all cases. It typically manifests as a secondary condition resulting from hematogenous dissemination originating from a primary pulmonary focus. Compared to primary aspergillosis, this scenario is associated with a mortality rate close to 90%.1

Sometimes, the clinical presentation can closely mimic that of other conditions, such as secondary cutaneous mucormycosis, leukemia cutis, or disseminated cutaneous cryptococcosis. Although not consistently evident, clinical signs can significantly aid in differentiation. For example, a necrotic facial eschar stemming from a paranasal sinus suggests mucormycosis, while umbilicated papules resembling molluscum contagiosum are suggestive of cryptococcosis. In cases with a of nonspecific or ambiguous clinical presentation, histopathology examinations prove invaluable in guiding diagnosis while awaiting microbiological confirmation. Sometimes it is not straightforward due to the overlap in morphological appearance among different fungal genera. Nevertheless, the identification of narrow, regularly septated hyphae branching in a “Y” shape is typical and suggestive of aspergillosis vs the thick, hyaline, non-septate, bifurcating hyphae associated with significant necrosis, thrombosis, and multiple tissue infarction seen in mucormycosis.2 In leukemia cutis, microorganisms are absent. Instead, a perivascular, periadnexal, nodular, or diffuse infiltrate of monomorphic leukemic cells is observed.3 Finally, in cryptococcosis, round fungal elements with a polysaccharide capsule that stains magenta with PAS, dark brown with Grocott, and red with mucicarmine are observed, in the absence of hyphae.4

This case illustrates a peculiar instance of secondary aspergillosis. First, we should mention the extensive involvement of all epidermal layers, a condition rarely described in primary cutaneous aspergillosis and never seen in secondary disseminations. Additionally, there is significant fat necrosis in the hypodermis, resembling pancreatic panniculitis, which is also uncommon in this type of mycosis.5 Furthermore, the pathogen involved, A. alliaceus, is exceedingly rare, with only three previous cases of human infection having been reported in the scientific medical literature currently available. The identification of Aspergillus species through molecular biology is an expedited and highly valuable procedure. Although it enables the differentiation between species that share similar morphology, it also possess inherent resistance to antifungal therapies and termed cryptic species, including A. alliaceus, which are associated with a worse prognosis and a higher mortality rate.6 Therefore, accurate identification of the Aspergillus species involved in each case is of paramount importance to determine the right therapeutic approach.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.