Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common, chronic, inflammatory skin disorder with high physical and emotional burden. AD usually starts in early childhood and has a heterogeneous course. Emerging evidence suggests that IL-4 and IL-13 are key cytokines in the immunopathogenesis of AD. Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody directed against IL-4 receptor α subunit, that blocks both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling. Data from Phase I-III studies revealed that dupilumab, administered as monotherapy or with topical corticosteroids, is effective and well tolerated in the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD. A large proportion of patients receiving dupilumab had significant improvements in multiple efficacy indexes, including Eczema Area and Severity Index, Investigator's Global Assessment and SCORing Atopic Dermatitis scores. These results introduce a new era of targeted therapies in the management of AD.

La dermatitis atópica (DA) es una frecuente enfermedad crónica e inflamatoria de la piel que acarrea una fuerte carga física y emocional. La DA suele comenzar a edades tempranas y tiene un curso heterogéneo. Las últimas evidencias a este respecto sugieren que las interleucinas IL-4 e IL-3 son citoquinas claves en la inmunopatogénesis de la DA. El dupilumab es un anticuerpo monoclonal dirigido contra la subunidad del receptor alfa de la IL-4 que bloquea la señalización tanto de la IL-4 como de la IL-3. Datos extraídos de estudios fase i-iii revelan que administrado como monotratamiento o acompañado de corticosteroides tópicos, el dupilumab se tolera bien y resulta efectivo en el tratamiento de pacientes adultos con DA de carácter entre moderado y grave. Un gran número de pacientes que recibieron dupilumab experimentaron mejorías notables en varios índices de eficacia, incluidos el Índice de gravedad y área de eccema, la Escala de evaluación global del investigador y la Escala de dermatitis atópica. Estos resultados abren una nueva era a tratamientos dirigidos en el manejo de la DA.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic inflammatory and incurable skin disease with an estimated prevalence of up to 25% in children and 5% in adults worldwide.1–5 AD frequently initiates during early childhood, however in up to 10% of cases its onset occurs in adults.4,6,7 Nearly 20% of patients have moderate-to-severe disease.2 The course of AD is heterogeneous and typically features with intermittent flares, with some patients developing persistent or chronic relapsing disease while others drop almost all symptoms until adolescence.8,9 AD is highly associated with other allergic comorbidities such as asthma, rhinusinusitis and food allergy,10,11 and higher risk for psychological diseases such as depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation,8,12–15 due to sleep disturbances mainly caused by intense itch. Recently, AD has been associated with other comorbidities, such as, obesity and cardiovascular disease, highlighting the possibility of AD being a systemic disorder.16 Moreover, AD is associated with high health care and socioeconomic costs due to work loss and negative outcomes on employer's productivity and profitability.17

ATOPIC DERMATITIS PATHOGENESISAD is a multifactorial disorder, including both genetic and environmental factors. Mutation in the epidermal structure protein filaggrin is a genetic risk of developing AD, however it not detected in all AD patients.18 AD is characterized by skin epidermal barrier disruption which leads to chronic inflammation with epidermal hyperplasia and cellular infiltrates, including T-cells, dendritic cells, eosinophils, and type-2 T-helper cell (Th2).19–21 The immune pathways observed in AD skin are Th2 dominant, secreting interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-13, IL-25, and IL-31, with some Th1, Th17 and Th22 contributions.19,22–24

IL-4 and IL-13 are key cytokines conducting Th2 activity and their actions include: (i) increased production of immunoglobulin E (IgE); (ii) elevated expression of chemokines such as thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARC) and eotaxin-3; (iii) attraction of inflammatory cells such as eosinophils and Th2 cells; (iv) inhibition of keratinocyte differentiation, expression of barrier proteins, such as filaggrin, synthesis of lipids and antimicrobial peptides, resulting in skin barrier dysfunction.25–33 AD patients’ skin barrier defect leads to skin dryness and increased amount of Staphylococcus aureus on lesional skin and elevated risk for infections.34,35

UNMET NEEDS IN THE TREATMENT OF ADThe treatment of AD remains challenging and limited.36 The majority of patients have mild disease, however about one-fifth suffers from moderate-to-severe forms.2,37,38 For mild forms, emollients and topical agents [topical glucocorticoids (TCS) and calcineurin inhibitors (TCI)] are generally enough to control symptoms, but treatment of moderate-to-severe AD is challenging. Topical therapy is usually unsatisfactory, and the use of systemic immunosuppressive agents, such as cyclosporine (the only systemic agent approved for AD), methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate-mophetil, is limited by their potential toxicities and side effects.39–44 Therefore, new effective and safer systemic therapeutic options are highly needed to treat moderate-to-severe AD.

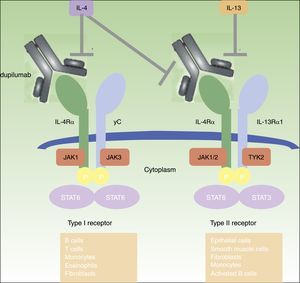

DUPILUMABDupilumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody (mAb) directed against the IL-4 receptor α (IL-4Rα) subunit that blocks both IL-4 and IL-13 signaling.45 IL-4 and IL-13 are highly increased in acute and chronic skin lesions of AD patients,19,46 and its inhibition proved to be very effective in adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD45–50 (figure 1). Dupilumab is the only biologic drug that has progressed to phase III clinical studies for the treatment of moderate-to-severe AD and is also being investigated in asthma, chronic sinusitis with nasal polyposis, and eosinophilic esophagitis.49

CLINICAL EFFICACY OF DUPILUMABPhase ITwo 4-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation phase I studies of dupilumab monotherapy were conducted in adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD – M4A and M4B – to evaluate its safety and efficacy.51 In M4A, 30 patients were randomized into 4 groups receiving placebo (n=6) or dupilumab – either 75mg (n=8), 150mg (n=8), or 300mg (n=8) once a week (qw). In M4B, 37 patients were randomized in 3 groups receiving placebo (n=10) or dupilumab – either 150mg/qw (n=14) or 300mg/qw (n=13). In both studies, treatment with dupilumab resulted in a fast, dose-dependent efficacy in all clinical outcomes.51 The achievement of a 50% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index score (EASI-50) by day 29 was significantly higher for all dupilumab doses combined compared to placebo (59% vs 19%, respectively; p<0.05). Significant improvement in other clinical endpoints was observed in the combined treatment groups by day 29 when compared with placebo, including the investigator's Global Assessment score (IGA), the Body Surface Area (BSA) percentage and the pruritus numeric rating scale (NRS).

Also, significant rapid dose-dependent changes in the RNA-expression profile in lesional skin were observed after 4 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, approaching non-lesional expression profiles and accompanying EASI improvement. An improvement of 24% and 49% was observed in lesional transcriptome in patients treated with dupilumab 150 and 300mg, respectively, as compared with a 21% shift to a lesional molecular phenotype in the placebo group (p<0.0001 for all groups).49 Also, the suppression in the expression of K16, a keratinocyte proliferation marker and regulator of innate immunity was observed, suggesting that dupilumab reduces epidermal hyperplasia.47

Phase IIbThe phase IIb trial was a 16-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study in which 380 adult subjects with moderato-to-severe AD were randomized to placebo (n=61) or dupilumab 100mg every 4 weeks (qw4) (n=65), 200mg every 2 weeks (qw2) (n=61), or 300mg/qw (n=63), qw2 (n=64) or qw4 (n=65).52,53 Overall, dupilumab demonstrated higher effectiveness when compared to placebo at all dosing levels. At week 16, EASI scores were significantly improved in the dupilumab groups versus placebo group. The least-squares (LS) mean percent improvement in EASI scores were -74% (300mg/qw), -68% (300mg/qw2), -65% (200mg/qw2), -64% (300mg/qw4), and -45% (100mg/qw4) compared with -18% for placebo (p<0.0001 for all comparison). Moreover, a greater proportion of patients in the dupilumab groups obtained an IGA 0/1. There were also meaningful improvements in the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) score (up to -56.9% for dupilumab 300mg/qw compared to -13.8% for placebo; p<0.0001 vs placebo) and BSA (up to -65.6% for dupilumab 300mg/qw compared to -7.7% for placebo (p<0.0001 vs placebo).49,52 Additionally, dupilumab was associated with pruritus improvement, as early as week 1. Except for 100mg/qw4, all doses of dupilumab demonstrated LS mean percentage decreases between 32.63% and 46.9% at week 16 (p<0.0001 for each comparison).52 Dupilumab also improved the quality of life of AD patients, with dose-dependent improvement of Dermatology Quality of Life Index (DLQI) from baseline through week 16 for all dose regimens (p<0.0001) besides 100mg/qw4.52(Table 1)

Efficacy outcomes in Phase IIb and III (SOLO 1 and 2) studies of dupilumab in atopic dermatitis at week 16.

| Outcome | Phase IIb Study$(52) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab 300mg once a week (n= 63) | Dupilumab 300mg every 2 weeks (n= 64) | Dupilumab 200mg every 2 weeks (n= 61) | Dupilumab 300mg every 4 weeks (n= 65) | Dupilumab 100mg every 4 weeks (n= 65) | Placebo once a week (n= 61) | |

| IGA 0/1 | 21 (33%) | 19 (30%) | 17 (28%) | 14 (22%) | 8 (12%)@ | 1 (2%) |

| EASI score, LS mean % change from baseline | -73.7% (5.2) | -68.2% (5.1) | -65.4% (5.2) | -63.5% (4.9) | -44.8% (5.0) | -18.1% (5.2) |

| Peak pruritus NRS scores, LS mean % change from baseline | -46.90% (4.61) | -40.06% (4.54) | -34.12% (4.72) | -32.63% (4.52) | -15.67% (4.49) | 5.15% (4.77) |

| SCORAD score, LS mean % change from baseline | -56.9% (4.1) | -51.2% (4.1) | -46.0% (4.1) | -48.8% (4.0) | -26.6% (4.0)@ | -13.8% (4.1) |

| BSA, LS mean % change from baseline | -65.6% (6.7) | -52.1% (6.6) | -54.5% (6.7) | -48.8% (6.4) | -26.2% (6.4)@ | -7.7% (6.7) |

| DLQI score, LS mean % change from baseline | -59.0% (7.14) | -39.6% (7.01) | -43.3% (7.18) | -37.4% (6.88) | -11.9% (6.88)& | 2.6% (7.34) |

| Outcome | SOLO 1$(54) | SOLO 2$(54) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab 300mg every other week (n=224) | Dupilumab 300mg every week (n=223) | Placebo (n= 224) | Dupilumab 300mg every other week (n=233) | Dupilumab 300mg every week (n=239) | Placebo (n= 236) | |

| IGA 0/1 | 85 (38%) | 83 (38%) | 23 (10%) | 84 (36%) | 87 (36%) | 20 (8%) |

| EASI score, LS mean % change from baseline | -72.3% (2.6) | -72.0% (2.6) | -37.6% (3.3) | -67.1% (2.5) | -69.1% (2.5) | -30.9% (3.0) |

| Peak pruritus NRS score, LS mean % change from baseline | -51.0% (2.5) | -48.9% (2.6) | -26.1% (3.0) | -44.3% (2.3) | -48.3% (2.4) | -15.4% (3.0) |

| SCORAD score, LS mean % change from baseline | -57.7% (2.1) | -57.0% (2.1) | -29.0% (3.2) | -51.1% (2.0) | -53.5% (2.0) | -19.7% (2.5) |

| BSA, LS mean change from baseline | -33.4 (1.4) | -34.3 (1.4) | -15.4 (1.9) | -30.6 (1.3) | -32.1 (1.3) | -12.6 (1.6) |

| DLQI score, LS mean change from baseline | -9.3 (0.4) | -9.0 (0.4) | -5.3 (0.5) | -9.3 (0.4) | -9.5 (0.4) | -3.6 (0.5) |

| HADS total score, LS mean change from baseline | -5.2 (0.5) | -5.2 (0.5) | -3.0 (0.7) | -5.1 (0.4) | -5.8 (0.4) | -0.8 (0.4) |

Data are presented in % (n), LS mean % change from baseline (SE) or LS mean change from baseline (SE).

Unless otherwise indicated, P<0.001 for the comparison between each regimen of dupilumab. @ P<0.05 versus placebo. & P=0.120 versus placebo.

EASI=Eczema Area and Severity Index. IGA=Investigator's Global Assessment. NRS=numeric rating scale. SCORAD=SCORing Atopic Dermatitis. BSA=Body Surface Area. DLQI=Dermatology Life Quality Index. LS=Least Square. SE=Standard Error.

Data taken from 52, 54

Two 16-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III studies of identical design evaluated dupilumab efficacy and safety.

In SOLO 1, 671 subjects were randomized to receive placebo (n=224), dupilumab 300mg/qw (n=224) or the same dose of dupilumab qw2 alternating with placebo (n=223).54 IGA scores of 0/1 at week 16 were achieved in 38 and 37% of the patients receiving dupilumab qw2 and qw, respectively, as compared to 10% of the patients in placebo group (p<0.001). The mean improvement of EASI score was approximately 70% in both groups of dupilumab, with 51 and 52% achieving EASI-75 at week 16 in the dupilumab qw2 and qw groups, respectively (p<0.001 vs placebo).54 Also, the LS mean percentage change from baseline at week 16 were -51.0% and -48.9% in peak pruritus NRS score, -57.7 and -57.0% in SCORAD score at week 16 in the dupilumab qw2 and qw groups, respectively (p<0.001 vs placebo).54

In SOLO 2, a total of 708 patients were randomized into 3 groups receiving placebo (n=236), dupilumab 300mg/qw (n=239) or the same dose of dupilumab qw2 alternating with placebo (n=233).54 At week 16, the endpoint IGA 0/1 was achieved in 36% in both dose regimen of dupilumab groups, compared to 20% in the placebo group (p<0.001). EASI-75 at week 16 was reported in 44 and 48% patients receiving dupilumab qw2 and qw, respectively (p<0.001 vs placebo). The LS mean percentage change from baseline were –44.3% and -48.3% in peak pruritus NRS score and -51.1 and -53.5% in SCORAD score at week 16 in the dupilumab qw2 and qw groups, respectively (p<0.001 vs placebo). Additionally, BSA and DLQI scores had great improvements at week 16 with all dupilumab dose regimens, in both studies.

In both SOLO trials a major impact in patients’ quality of life was observed, with significant reduction of symptoms of anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).54(Table 1)

LIBERTY AD CHRONOSA 52-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study was conducted in adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD to evaluate safety and efficacy of dupilumab in association to TCS. 740 patients were randomized into 3 groups receiving placebo (n=315) or dupilumab 300mg/qw (n=319) or q2w (n=106), plus TCS. IGA 0/1 at week 16 was observed in 39% of patients in both dupilumab groups versus 12% of patients in the placebo group (p<0.0001 vs placebo); EASI-75 at week 16 was achieved by 64% of patients treated with dupilumab qw and 69% of patients receiving dupilumab q2w, versus 23% of patients of the control group (p<0.0001 vs placebo)55; peak pruritus NRS improvement of 4 or higher at week 16, was achieved by more than one-half of patients in both dupilumab groups versus 20% of patients receiving placebo (p<0.0001 vs placebo). Identical effectiveness was observed at week 52 for these 3 clinical endpoints. Dupilumab also improved all other indices at weeks 16 and 52, including SCORAD, BSA and DLQI scores. (Table 2) Dupilumab was also associated with more days free of TCS, lower rates of rescue medication use, and reduction of the AD flares over the 52-week treatment period compared to placebo.55

Efficacy outcomes in Phase III Study of dupilumab in atopic dermatitis – LIBERTY AD CHRONOS – at week 16 and 52.

| Outcome | LIBERTY AD CHRONOS$(55) Week 16 Week 52 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab 300mg q2w + TCS (n=106) | Dupilumab 300mg qw + TCS (n=319) | Placebo qw + TCS (n=315) | Dupilumab 300mg q2w + TCS (n=89) | Dupilumab 300mg qw + TCS (n=270) | Placebo qw + TCS (n=264) | |

| IGA 0/1 | 39% (41) | 39% (125) | 12% (39) | 36% (32) | 40% (108) | 13% (33) |

| EASI-75 | 69% (73) | 64% (204) | 23% (73) | 65% (58) | 64% (173) | 22% (57) |

| EASI score, LS mean % change from baseline | -76.7% (3.77) | -77.3% (2.22) | -43.2% (2.26) | -78.3% (4.44) | -80.3% 82.64) | -45.8% (2.70) |

| Peak pruritus NRS scores, LS mean % change from baseline | -56.2% (3.38) | -54.8% (1.99) | -28.6% (2.03) | -56.2% (4.38)* p=0.0001 | -54.4% (2.60) | -27.1% (2.66) |

| SCORAD score, LS mean % change from baseline | -62.1% (2.61) | -63.35 (1.53) | -31.8% (1.55) | -66.2% (3.14) | -66.1% (1.85) | -34.1% (1.88) |

| BSA, LS mean change from baseline | -38.6 (1.88) | -37.4 (1.11) | -18.6 (1.13) | -41.5 (2.19) | -39.9 (1.30) | -20.3 (1.33) |

| DLQI score, LS mean change from baseline | -9.7 (0.51) | -10.5 (0.30) | -5.3 (0.31) | -10.9 (0.59) | -10.7 (0.36) | -5.6 (0.36) |

| HADS total score, LS mean change from baseline | -4.9 (0.56)** p=0.03 | -5.2 (0.33)* p=0.0004 | -3.6 (0.34) | -5.3 (0.65)* p=0.0109 | -5.5 (0.39) | -3.4 (0.40) |

Data are presented in % (n), LS mean % change from baseline (SE) or LS mean change from baseline (SE)

Dupilumab was well tolerated and had a favorable safety profile across all studies, with the majority of adverse events (AEs) being classified as mild or moderated in severity and transient in duration. Serious AEs (SAEs) were globally infrequent across all studies.51,52,54(Tables 3, 4).

Adverse events in Phase I (M4A and M4B) and IIa (M12 and C4) studies of dupilumab in atopic dermatitis*

| AEs | M4 A and M4B combined49–51 | M1249–51 | C449–51 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab (n=51) | Placebo (n=16) | Dupilumab (n=55) | Placebo (n=54) | Dupilumab+ TCS (n=21) | Placebo + TCS (n=10) | |

| Any AE | 44 (86%) | 14 (88%) | 42 (76%) | 43 (80%) | 12 (57%) | 7 (70%) |

| Serious AEs | 1 (2%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 7 (13%) | 0 | 1 (10%) |

| AE leading to study discontinuation | 0 | 1 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 3 (6%) | 0 | 1 (10%) |

| Skin infections | 2 (4%) | 2 (13%) | 3 (5%) | 13 (24%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (10%) |

Adverse events in Phase IIb and III (SOLO 1 and 2, and LIBERTY AD CHRONOS) studies of dupilumab in atopic dermatitis*

| AEs | Phase IIb52 | SOLO 1 and SOLO 254 | LIBERTY AD CHRONOS55 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab (all dosing groups combined) (n=318) | Placebo (n=61) | Dupilumab (all dosing groups combined) (n=920) | Placebo (n=460) | Dupilumab (all dosing groups combined) (n=415) | Placebo (n=315) | |

| At least 1 AE | 258 (81%) | 49 (80%) | 628 (68%) | 313 (69%) | 358 (86%) | 266 (84%) |

| At least 1 serious AE | 12 (4%) | 4 (7%) | 21 (2%) | 24 (5%) | 13 (3%) | 16 (5%) |

| AE leading to study discontinuation | 21 (7%) | 3 (5%) | 13 (1%) | 7 (2%) | 11 (3%) | 24 (8%) |

| Injection-site reactions | 22 (7%) | 2 (3%) | 123 (13%) | 28 (6%) | 66 (16%) | 24 (8%) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 89 (28%) | 16 (26%) | 87 (9%) | 39 (9%) | 85 (20%) | 61 (19%) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 23 (7%) | 11 (18%) | 33 (4%) | 10 (2%) | 54 (13%) | 32 (10%) |

| Herpes viral infections | 26 (8%) | 1 (2%) | 46 (5%) | 17 (4%) | 30 (7%) | 25 (8%) |

| Skin infections | 21 (7%) | 5 (8%) | 55 (6%) | 44 (10%) | 38 (9%) | 56 (18%) |

| Conjunctivitis** | 21 (7%) | 2 (3%) | 60 (7%) | 7 (2%) | 76 (18%) | 25 (8%) |

| AD exacerbation | 54 (17%) | 11 (18%) | 121 (13%) | 148 (32%) | 72 (17%) | 144 (46%) |

| Headache | 34 (11%) | 2 (3%) | 73 (8%) | 24 (5%) | 29 (7%) | 19 (6%) |

In phases I-III studies, the most common AEs were nasopharyngitis, injection-site reactions, headache, exacerbation of AD and skin infections. In all these trials, nasopharyngitis’ incidence was balanced across dupilumab and placebo groups, whereas exacerbations of AD and skin infections were more common in patients receiving placebo.54

SAEs were more common with placebo than dupilumab across all studies, as well as SAEs of skin infections, with an incidence across all phase I and IIa studies 4-times as high as the incidence in the dupilumab groups (0.20 vs 0.05, respectively).51 In phase IIb study, serious exacerbations of AD (2% in both groups) and serious infections (<1% with dupilumab vs 0% with placebo) were similar and rare in both groups.52 In SOLO-1 and -2, skin infections occurred in approximately 6% of patients receiving dupilumab, and in 8 to 11% of those receiving placebo, whereas dupilumab was not associated with increased overall risk of infections in CHRONOS.54,55

Herpes viral infections were more common in subjects receiving dupilumab than in those receiving placebo in phase IIb study (8% vs 2%, respectively), SOLO-1 and -2 (5% in both studies vs 4% and 3%, respectively), and CHRONOS (7% vs 8%, respectively). This finding was not reported in phases I and IIa trials.

A higher incidence of conjunctivitis was observed among treatment groups compared to placebo in phase IIb study (7% vs 3%, respectively), SOLO-1 and -2 (8% and 5% vs 2% and 1%, respectively), and CHRONOS (18% vs 8%, respectively), and most cases were mild-to-moderate.52,55 Solely 2 patients receiving dupilumab discontinued study treatment due to conjunctivitis.56

No deaths were reported in phase I and II studies, while 3 deaths were reported in the phase III studies, although none appeared to be associated with dupilumab.

SAEs that led to drug and study discontinuation were low across all studies, with the majority occurring with placebo, except in phase IIb study (7% with dupilumab vs 5% with placebo). In CHRONOS, one-half of patients withdrew from the study due to AD flares in the placebo group, and one due to conjunctivitis in the dupilumab qw group.

DISCUSSIONData from the dupilumab trials in more than 2000 patients has demonstrated its clinical effectiveness in adult patients with moderate-to-severe disease. The strength of these findings was supported by significant improvements in multiple efficacy indexes, including EASI, IGA, BSA, peak pruritus NRS and DLQI scores.52 An EASI-75 response was achieved in more than half of patients enrolled in all trials and a IGA 0/1 score was also more frequently reported in the dupilumab groups across all studies. Furthermore, a meaningful and relevant diminution of pruritus was observed with dupilumab treatment as well as significant reductions in symptoms of anxiety and depression. Since pruritus is a significant contributor to the negative impact of AD on patients’ quality of life, dupilumab might provide life-changing benefits in health-related quality of life and metal health for many patients.

Overall dupilumab was well tolerated and had a favorable safety profile across all studies, with most of AEs classified as mild or moderate, with a similar rate to placebo and without dose-limiting toxic effects. Herpes viral infections occurred more commonly in dupilumab-treated patients, although, till date blockade of IL-4 and IL-13 signaling has not been considered a potential risk factor for these infections.52,54 In addition, patients with AD have a greater risk of developing skin infections when compared to the general population, presumably due to the disruption of skin barrier. Interestingly, skin infections were observed more frequently in the placebo groups, probably because the cutaneous disturbance remained untreated.26 Dupilumab might be neither immunosuppressive nor associated with increased risk of infection, but rather restorative of barrier and immune function.55 An increased incidence of allergic and non-allergic conjunctivitis was observer across all studies, but the cause is unclear. Conjunctivitis occurred more frequently in patients who had severe disease or coexisting allergic conjunctivitis, and the vast majority was mild or moderate and resolved during study treatment.55,56 This AE was not increased with dupilumab in studies involving patients with asthma or nasal polyposis, suggesting a specific mechanism associated to AD, not an inherent effect of dupilumab.54–57 There seems to exist an inverse relationship between serum concentrations of dupilumab and conjunctivitis, suggesting that local undertreatment may play a role.56

It is difficult to extrapolate dupilumab data to children, the most frequently affected population, but phase IIa and III studies with children (NCT02407756 and NCT02612454) are ongoing and their results will help determine dupilumab efficacy in this age group. Additionally, long-term follow-up data from extension studies and registries are necessary to exclude uncommon AEs, and to evaluate the efficacy, tolerability and safety of long-term treatment with dupilumab.

Other drugs are being tested in patients with AD including: (i) nemolizumab (anti-IL-31), with results from a phase II study showing significant reduction in pruritus measures when compared with placebo, with some reductions in other AD-associated clinical parameters58; (ii) tralokinumab and lebrikizumab (anti-IL-13), so far showing good safety profiles; (iii) tezepelumab (anti-TSLP), OX40 ligand antagonist, ILV-094 (anti-IL-22), secukinumab (anti-IL-17), omalizumab (anti-Fc receptor of IgE), apremilast (anti-PDE4) and JAK inhibitors tofacitinib and baricitinib, in ongoing studies without results so far; (iv) tocilizumab (IL-6 receptor/IL-6R antagonist), demonstrating significant improvement in AD clinical scores, but with higher infection rates reported.59 These agents may hold promise for AD, however larger studies are necessary to evaluate their potential role in this skin disease.

Dupilumab may have the potential to revolutionize the treatment of AD in the coming years, allowing a therapeutic targeted approach in clinical practice similar to what occurred for psoriasis several years ago. Dupilumab may be for AD what TNF-α inhibitors were to psoriasis: effective and safe therapies that might represent a quantum leap forward in the physicians’ ability to help to improve the patients’ lives.60 The next years may enlighten the economic burden on healthcare systems by the use of dupilumab as a systemic drug for AD, although dupilumab will probably be reserved for severe cases of AD that do not respond to traditional therapies, even if it is superior in clinical trials.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ferreira S, Torres T. Dupilumab para el tratamiento de la dermatitis atópica. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:230–240.