At numerous scientific meetings and in publications by the Working Groups and members of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV), population studies and descriptions of clinical cases are reported with references to the race, ethnicity, or ancestry of the patients, using terms like Caucasian, Latino, Hispanic, and others. These categories reflect the usage in journals published in the United States of America (U.S.) and the terms are often used inconsistently.

The classification of human populations based on phenotypic characteristics is a topic that generates considerable controversy for scientific, historical, and ethical reasons. It is, however, undoubtedly useful in the field of dermatology, both because of the need to supply an approximate reference of skin color in the description of a patient and because of the higher prevalence of or susceptibility to certain diseases within certain groups, independent of environmental factors. For that reason, and without losing sight of the fact that this is a thorny issue, a brief review of the subject and a proposal for an agreed classification are needed.

Today, race is deemed to be a social construct, based on similarities in physical traits (facial characteristics and constitutive skin or hair color, for example) but also influenced by anthropological and social factors, and intimately associated with racism (political or scientific). The term race was originally used to refer to a nation or ethnic group. However, starting in the 18th century, and with the expansion of European colonialism, classification schemas based on geographical origin, skin color, and facial and cranial morphology were introduced. Each race was then associated with different predispositions and intellectual capacities (racial essentialism) and the classifications were used to justify slavery.

Carl Linnaeus, in his work Systema Naturae (1735), divided the human species into 4 continental varieties based primarily on skin and eye color and hair characteristics: Europaeus albescens, Americanus rubescens, Asiaticus luridus, and Africanus or Afer niger. He associated each variety with different predispositions (moods) and temperaments, and applied explicit value judgments.1

Some Enlightenment thinkers, such as Kant and Hume, promoted a hierarchical theory of race that asserted the superiority of the white European race, a thesis that contributed to the ideological underpinnings used to justify slavery and later, once slavery had been abolished in the USA, racial segregation.1

In the third edition of his doctoral thesis (1795), Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, one of the founders of anthropology, included a classification of humans based on craniometry, dividing the species into 5 races: Caucasian; Mongolian; Ethiopian; American; and Malayan.2 (It should be noted that in Spanish the term Caucasian referring to a person's physical appearance or origins is translated as caucásico, and the adjective used to refer to the Caucasian region situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea is caucasiano.) Although he considered the skull of a Georgian woman to be the most beautiful and symmetrical of his specimens, Blumenbach did not establish any kind of hierarchy of value and the connotations that have subsequently been attributed to his classification are due to English translations made in the 19th century.3 Blumenbach believed that transitions between groups were gradual; he affirmed the unity of the human species and also recognized the existence of heterogeneity within any given geographical region.4

At the beginning of the 20th century, many anthropologists considered race to be a biological phenomenon aligned with linguistic, cultural, and social groupings and one that largely determined the behavior and identity of the individual. Following the traumatic experiences of Nazism and other genocides and with the rise of the anti-colonial and civil liberties movements, scientific racism has been generally discredited and radical alternatives have been proposed, such as abandoning the use of racial categories altogether because of their association with racism.5 Such strongly ideological proposals have some scientific basis in the nature of gene flow between populations and in the geographic gradation of human genotypes and phenotypes (clines), which may be discordant (for example, skin color and blood groups). However, while the concept of continental groupings or human races (implying genetic differences with taxonomic significance) may lack true biological or evolutionary significance and inasmuch as categories are not useful for the purposes of individualized medicine, they do have important epidemiological implications.6

Describing and categorizing the genetic variations between populations based on geography and ancestry has always been difficult, and is even more complex today given current high levels of population migrations thus, the use of such terms as race, Caucasian and Negro has almost completely disappeared from the genetic literature,7 largely because of the ideological or offensive implications associated with these classifications. There are, however, perfectly valid alternatives to the term race, such as ancestry, which would seem more appropriate than ethnicity because of the predominant cultural component in ethnic identity.

The genetic differentiation of populations is favored by geographical isolation and endogamy (cultural, social or religious) and reduced by migration and heterogamy. The highest level of genetic diversity is found in Africa; in the successive migrations out of Africa, genetic variation was lower but the differentiation from the original African populations increased. Recent human population genetic studies have recapitulated the classical definitions of race based on continental ancestry: African, Caucasian (European and Middle East), Pacific Islander, Asian, and Native American.8

During the 20th century, the term Caucasian fell into disuse and was replaced by the term Caucasoid, including numerous subclassifications now considered pseudoscientific, but the term Caucasian is still used in the United States as a synonym for White in population censuses and naturalization laws (as a self-defined category). The U.S. Census Bureau's classification was designed to promote equal employment opportunity and to address disparities in health and environmental risks,9 but it currently plays a very important role because the classification is used in most of the epidemiological studies, clinical trials, and medical research conducted in the U.S.10 and, by extension, worldwide.

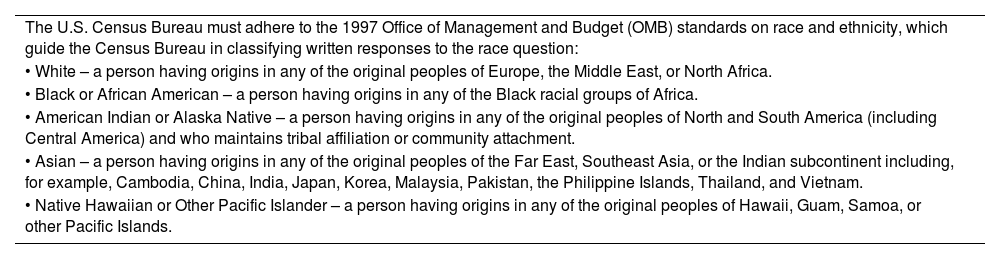

The classification used since 1997 in the responses to the U.S. Census Bureau's race questionnaire is shown in Table 1.9 Respondents can choose more than one race when answering the questions. In 2015, the Bureau considered the addition of “Middle Eastern and North African” as a separate category11 but this change has not been implemented.

Definition of Self-Identified Race in the Questionnaires of the U.S. Census Bureau.

| The U.S. Census Bureau must adhere to the 1997 Office of Management and Budget (OMB) standards on race and ethnicity, which guide the Census Bureau in classifying written responses to the race question: |

| • White – a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa. |

| • Black or African American – a person having origins in any of the Black racial groups of Africa. |

| • American Indian or Alaska Native – a person having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America (including Central America) and who maintains tribal affiliation or community attachment. |

| • Asian – a person having origins in any of the original peoples of the Far East, Southeast Asia, or the Indian subcontinent including, for example, Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippine Islands, Thailand, and Vietnam. |

| • Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander – a person having origins in any of the original peoples of Hawaii, Guam, Samoa, or other Pacific Islands. |

The racial categories used in the U.S. Census Bureau questionnaire reflect the current social definition of race in the U.S. and were never intended to establish or represent any biological, anthropological or genetic definition of race.9 The U.S. census also recognizes that some categories relate exclusively to sociocultural or national origin groupings, such as the classification “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin”—an “ethnic identity” defined as follows:

The category “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin” includes all individuals who identify with one or more nationalities or ethnic groups originating in Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Central and South America, and other Spanish cultures. Examples of these groups include, but are not limited to, Mexican or Mexican American, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Salvadoran, Dominican, and Colombian. “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin” also includes groups such as Guatemalan, Honduran, Spaniard, Ecuadorian, Peruvian, Venezuelan, etc. If a person is not of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin, answer “No, not of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.”12

Although it may be useful for the U.S. Census Bureau purposes, a category based on self-identified national or cultural identity is not appropriate for use in scientific or medical research.

In conclusion, while the classification of race is based on a small number of genes that determine the individual's physical appearance and since it does not reflect the enormous genetic variability within populations and may have ethically unacceptable implications, some kind of classification is nonetheless useful for epidemiological, clinical, and research purposes.13 It would, therefore, be advisable to standardize the terminology used and, with all its limitations, the system used by the U.S. Census Bureau is widely employed and would be quite appropriate (excluding the ethnic category mentioned above). For the reasons discussed above, the proposal for an adapted translation is as follows:

Classification based on the geographical origin of ancestors:

- •

Blanco (White). This term is perhaps preferable to “Caucasian” and would include people having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa.

- •

Negro (Black). People having origins in any of the population groups in sub-Saharan Africa. In the Spanish language as spoken in Spain, the term Negro is equivalent to the term Black in English and does not, in principle, have offensive connotations. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_ethnic_slurs).

- •

Amerindio (American Indian). A person having origins in any of the original peoples of North and South America.

- •

Asiático (Asian). A person having origins in any of the diverse populations of the Indian subcontinent, China, Far East, or Southeast Asia.

- •

Otros (Other). This category would include, among others, people having origins in the Pacific Islands or any of the original peoples of Oceania).

- •

Mixto (Mixed). This category would be used when a person includes more than one category in their self-identification; all the categories selected should be listed).

In any case, for both scientific and ideological reasons, this is a complex and difficult subject to address. From the point of view of population genetics, the relationship between geographic and genetic ancestry is not straightforward, and there are in fact no European directives or guidelines on this subject.

The JAMA network of journals has published an extensive guide (focused primarily on U.S. practice) which, recognizing the social nature of constructs such as race and ethnicity, affirms the importance of including their description in medical publications to help identify possible health disparities or inequities14; on the other hand, a classification with few categories does not help identify the high prevalence of autosomal recessive diseases (such as Gaucher disease or Bloom syndrome) in relatively small communities with a high degree of inbreeding.

The use of terms such as “etnia” (ethnic group) and “etnicidad” (ethnicity) would be incorrect in this context, because they include a component of cultural and sociological identity that has no genetic association. The term “raza” (race) is inappropriate both for scientific reasons and because of its ideological and political connotations. In conclusion, the term “ascendencia” (ancestry) would appear to be the most appropriate, although any such categorization should always be self-defined and the individual should be offered the possibility of a multiple choice response.

The author would like to thank Professor Jordi Surrallés, Chair of Genetics at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, for his critical reading of this manuscript and his excellent comments.