Cutaneous melanoma is an extremely aggressive malignant tumor arising from melanocytes and accounting some 15% of all cancers. Incidence varies from 3–5 cases per 100000 inhabitants and year in the Mediterranean region to 12–20 cases per 100000 inhabitants and year in Nordic countries, and is still increasing worldwide. Cutaneous melanoma is believed to be a cancer that primarily affects white skin, and the risk of developing these tumors is 10 times higher in white-skinned populations than in those with darker skin.1,2 Melanoma is known for its aggressiveness, and metastases to bones, lungs, brain, liver, or lymph nodes are expected. However, there have been very few reports of oral metastases,3 which mainly affect the gingiva, tongue, tonsils, and mandible.4,5

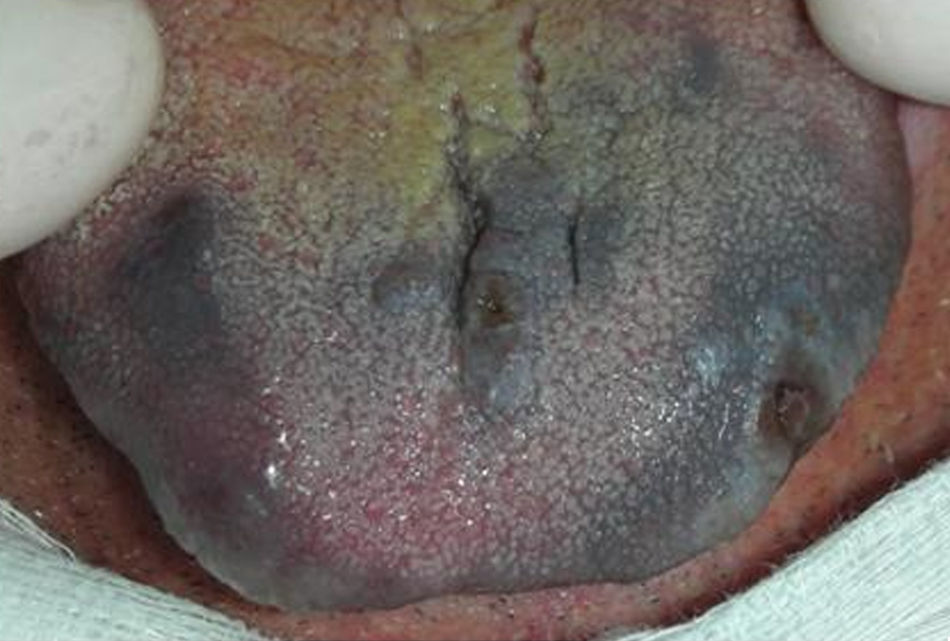

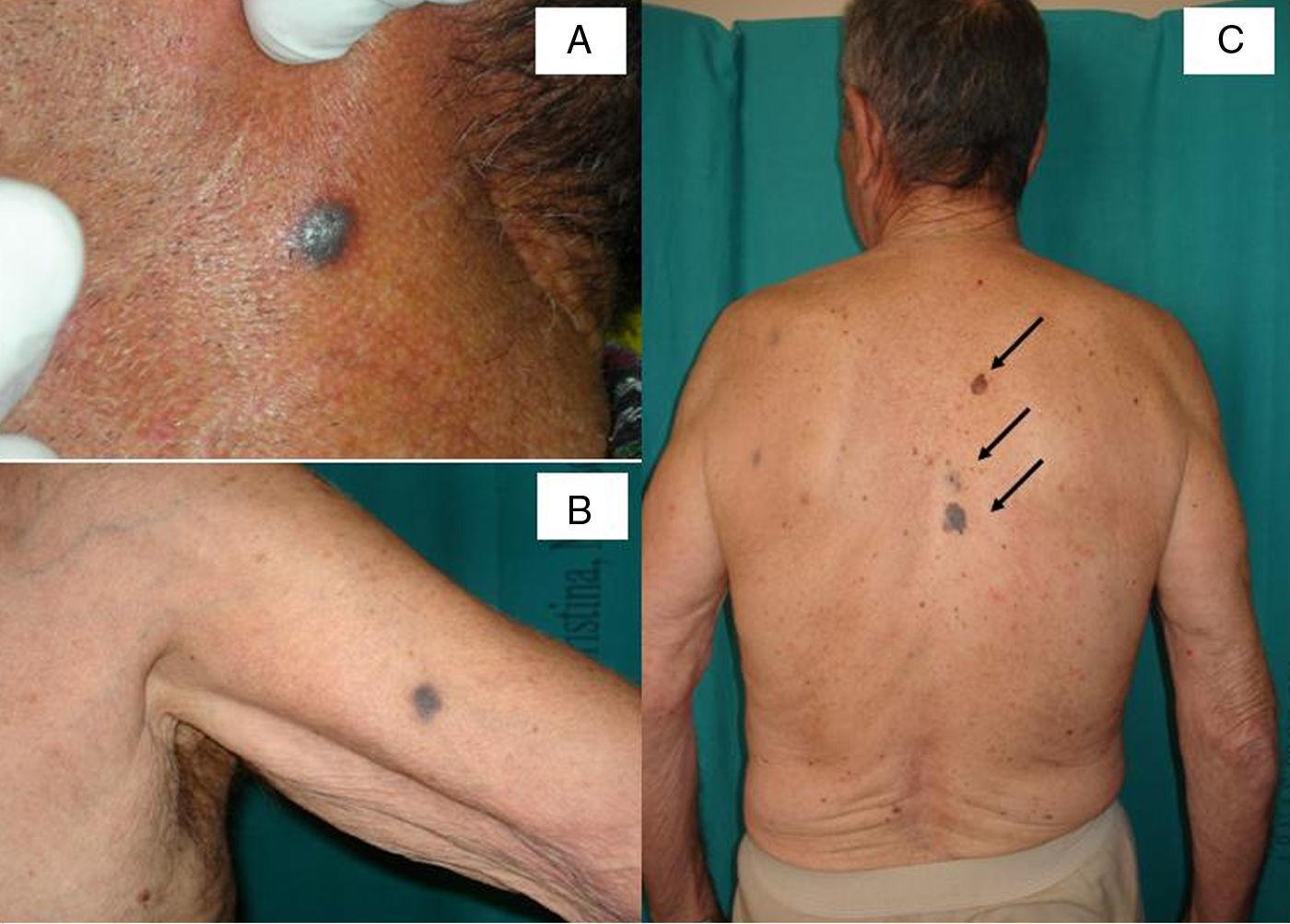

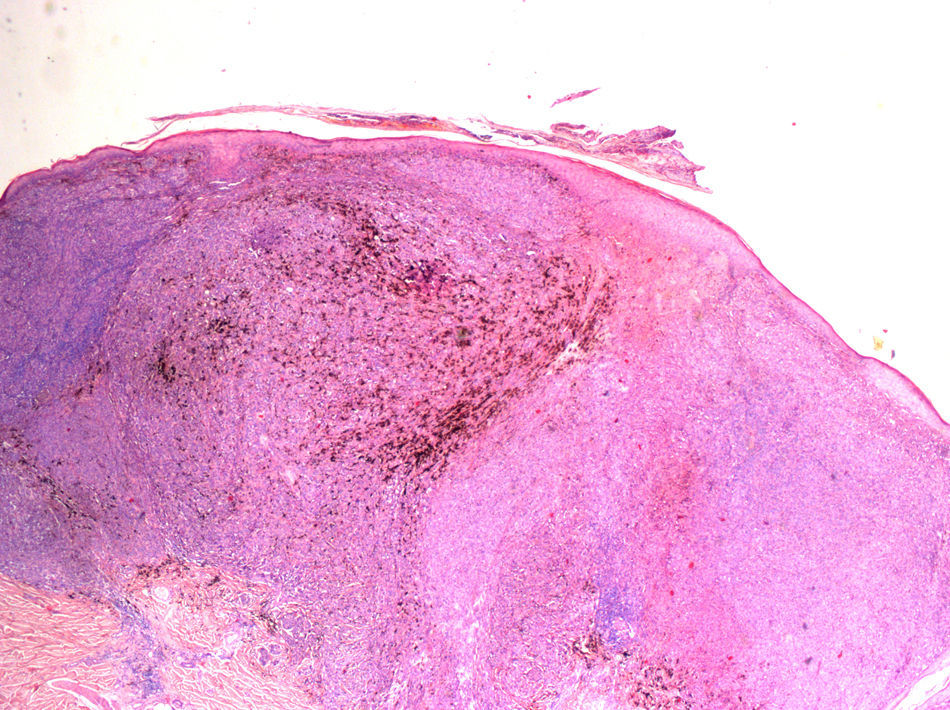

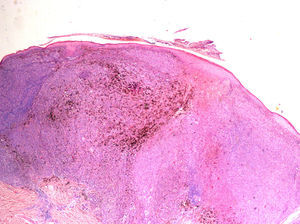

We describe the case of an 86-year-old white man admitted with a black lesion on the tongue that had persisted for about 2 months. During the consultation, the patient rejected the idea that he had a disease and complained about the appearance, concurrently with the lingual lesions, of dark nodules on his neck and upper limbs associated with intense and persistent itching, which had on occasion spread to the trunk. These skin lesions had been treated with antihistamines and topical corticosteroids prescribed initially by his family physician and subsequently by a dermatologist, without clinical improvement. Intraoral examination revealed the presence of a wide, irregularly shaped, sepia-black macular lesion that was firm to the touch and asymptomatic, extending from the dorsal to the ventral surface of the tongue. This was associated with small stiff nodules with an ulcerated surface on the left margin and the midline of the anterior third of the tongue (Fig. 1). Extraoral examination (Fig. 2A and B) revealed the presence of blackish oval nodular lesions, palpable and painless, localized to the neck and upper limbs. A diffuse cervical lymphadenopathy was also detected. These clinical findings gave rise to a suspected diagnosis of oral melanoma. While considering it important to establish whether the oral lesions were primary or metastatic, we preferred to start the diagnostic work-up of the suspected melanoma with an examination of the skin lesions. The results of routine blood tests were within normal limits, with the exception of an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Tests for neoplastic markers revealed the carcino-embryogenic antigen. A more detailed clinical and dermoscopic examination of the skin (Fig. 2C) revealed the following findings: a) a brown-black variegated pigmented nevus on the spinal column between the shoulders, irregular in shape and color measuring 21×16mm (Fig. 2C, third arrow) and characterized by a blue–gray veil and irregularly shaped globules; the presumptive diagnosis was melanoma with in-transit metastases (Fig. 3A); b) 3 pigmented blue-brown lesions (Fig. 2, C, second arrow) situated 14mm from the first lesion; and c) an irregularly shaped variegated brown lesion on the right parascapular region, of 14×15mm (Fig. 2C, first arrow) characterized by a fragmented thickened network and areas of regression, consistent with the diagnosis of melanoma (Fig. 3B and C). Histopathology examination of an incisional biopsy of the parascapular lesion showed a dermis colonized by atypical epithelioid cells indicating a melanoma (Fig. 4). Unexpectedly, after the diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma was confirmed, the patient refused to undergo oral biopsy.

A diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma with oral metastases was confirmed on the basis of the clinical, dermoscopic, and histological data. A chest radiograph demonstrated no active parenchymal lesions.

A computed tomography scan of the maxillofacial region, neck, brain, thorax and abdomen revealed no further metastases, but generalized lymphadenopathy. Due to the presence of in-transit metastases, sentinel lymph-node biopsy was not performed, as recently reported.6

The patient was referred to an oncology unit, but no therapeutic regimen was undertaken given his age, his refusal to consent to treatment, and the number and extent of his lesions.

Melanoma is a tumor caused by the malignant transformation of melanocytes, a cell line derived from the neuroectoderm. Although the skin continues to be the most frequent site of primary disease (95% of cases), the embryologic origin of melanocytes explains why melanoma is not exclusively a skin cancer.1 In fact, melanomas may also arise in extracutaneous sites, including the mucosal surfaces of the respiratory, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts and other sites where neural crest cells migrate.7

The appearance of a primary melanoma located in the oral cavity is very rare, accounting for only 1–2% of all mucosal melanomas and 0.5% of all oral malignancies; secondary or metastatic forms are even more rare.3,8 When the maxillofacial region is involved, metastases of cutaneous melanoma are mainly reported in the tongue, tonsils, mandible, gingiva, and parotid glands.

When a patient presents with a pigmented oral lesion, an extraoral clinical examination should be performed; in fact, according to Greene and coworkers,4,9 in order to consider an oral melanoma as primary, the following 3 criteria must be met: a) demonstration of melanoma only in the oral cavity; b) presence of junctional activity; and c) inability to demonstrate extra-oral primary melanoma.

In our case, the presence of a cutaneous lesion with a histopathological diagnosis of melanoma allowed us to consider the oral lesions as metastatic.

When analyzing a suspicious skin lesion, it is important to bear in mind the ABCD rule in which A refers to asymmetry, B to border irregularities, C to color heterogeneity, and D to dynamics (in color, elevation, or size).2 Furthermore, it has been noted, that dermoscopy always enhances the diagnostic accuracy and identifies lesions that must be biopsied,10 as was the case in this patient.

In conclusion, the appearance of a metastatic lingual melanoma is a very rare event, hence close collaboration among different specialists is very important in case of suspicious pigmented lesions to ensure their early detection and a prompt treatment of such aggressive neoplasm.