Ibrutinib is a Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor approved for the management of relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma (MCL), and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Ibrutinib is also being studied as a potential therapy for various dermatological conditions including graft-versus-host disease, chronic spontaneous urticaria, pemphigus, and systemic lupus erythematosus, with promising preliminary results in some cases.1–3

Although cutaneous adverse events are a common finding in patients on ibrutinib,4,5 no cases of lymphocytic vasculitis (LyV) have been reported in the medical literature to this date.

A 57-year-old man was admitted to the dermatology department. He had a significant past medical history of stage IV blastic MCL, and had been treated with first-line chemotherapy with R-CHOP/R-DHAP (rituximab, cyclophosplamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone/rituximab dexamethasone, cytarabine, cisplatin), autologous stem cell transplantation, and rituximab, with progressive disease. He was also treated with second-line chemotherapy with ibrutinib (560mg/day) with progressive disease, and third-line chemotherapy with autologous CAR-T19 achieving complete remission.

While on ibrutinib, he had a 3-week history of multiple erythematous papular lesions on legs and arms (Fig. 1). He reported previous episodes of similar lesions that remained unexamined by the dermatologist, with the concomitant administration of ibrutinib, and spontaneous resolution. No systemic symptoms, previous history of cutaneous, autoimmune disease, or drug reactions were reported. ANCA and serologic testing for multiple infections all tested negative including the RT-PCR assay for SARS-CoV-2. Eight days later the lesions resolved spontaneously, without need for treatment discontinuation.

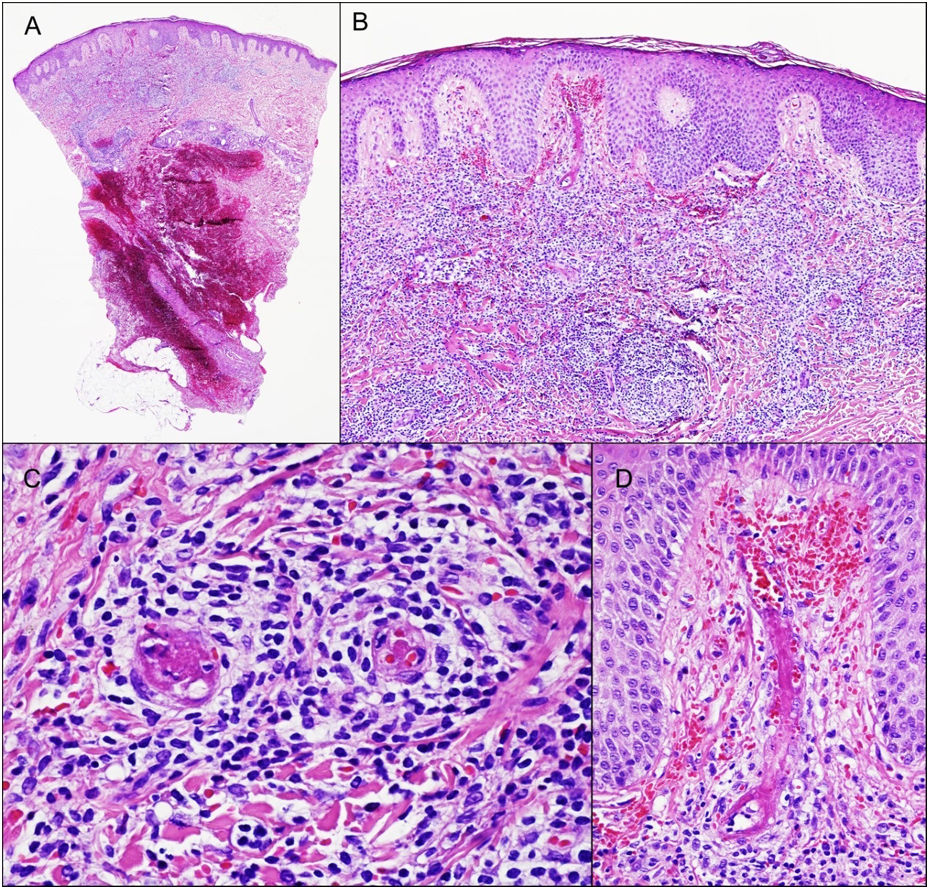

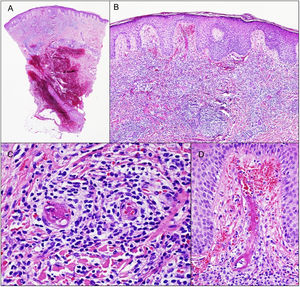

One of the lesions was biopsized revealing the presence of a dense infiltrate of lymphocytes, monocytes, and scattered eosinophils around small and medium sized vessels on the superficial and deep dermis. Images of LyV were seen, with cells reaching the vessel walls, which showed marked endothelial tumefaction, luminal thrombotic occlusion, fibrin deposition and red blood cell extravasation (Fig. 2). The epidermis showed slight spongiosis with irregular acanthosis. Immunohistochemical staining showed a reactive CD3+ T cell infiltrate with a mixture of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes and scattered CD20+ B lymphocytes. CD5, SOX11, and cyclin D1 confirmed the absence of MCL.

The biopsy revealed the presence of a dense inflammatory infiltrate on the superficial and mid dermis composed mainly of lymphocytes (A, B). Images of lymphocytic vasculitis were seen, with endothelial tumefaction, luminal thrombotic occlusion, fibrin deposition, and red blood cell extravasation (C, D).

Cutaneous toxicity has been reported as one of the most common non-hematological side effects of ibrutinib. Some authors have reported ibrutinib-related skin rashes in 13–27% of the patients with CLL and MZL.4,5 The rashes can range from asymptomatic ecchymosis, nonpalpable petechial rash, to leukocytoclastic vasculitis-like palpable purpura.4,5 Pileri et al.6 reviewed the cutaneous adverse events of patients treated with ibrutinib at their center. Paronychia of the nail fold was described in 7 out of 50 patients on ibrutinib, in some cases along with pyogenic granuloma, while 9 patients experienced eczematous reactions. Other findings include 1 case of angular cheilitis and acute glossitis, fungal infection, and perinasal impetigo.

Our patient showed LyV. To date 5 patients on ibrutinib have been identified with leucocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) but none with LyV.

Other ibrutinib-related skin reactions include neutrophilic dermatosis,7 panniculitis with or without vasculitis, and bilateral, purpuric, painful cutaneous nodules consisting of a mixed lymphocytic, neutrophilic and granulomatous inflammation.8

Cutaneous lymphocytic vasculitis is an inflammation of blood vessels with the potential to damage the skin and other organs of the body. The etiopathogenesis of cutaneous lymphocytic vasculitis is not fully understood, but it is believed to be an autoimmune response triggered by various factors, being infections, drugs, and connective tissue diseases the main ones.1

In our case, the main dermatopathological differential diagnosis is leukemic vasculitis,9 a specific form of vasculitis, mediated by leukemic blast cells rather than reactive inflammatory cells. In our patient, both the immunohistochemical studies and the benign course of the lesions ruled out this possibility.

In conclusion, we report the first case of ibrutinib-related lymphocytic vasculitis with spontaneous resolution, which did not require treatment discontinuation. The origin of this disorder is still unclear, but could be associated with an abnormal drug-induced inflammatory response.

FundingThis study received no funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.