Anetoderma is a rare acquired chronic skin condition that involves the loss of elastic fibers. There is no specific effective treatment.1,2 We present the case of a patient with primary anetoderma associated with both primary Sjögren syndrome and anticardiolipin antibodies. Biopsy showed an acute inflammatory infiltrate observed in the reticular dermis. The condition was treated with colchicine and dapsone.

The patient was a 21-year-old woman with a history of depression and bulimia, for which she was receiving effective duloxetine treatment; she had no recent changes in weight. She was first referred to our hospital's dermatology department in June 2009 for painful 5-mm erythematous papules that had appeared gradually and were progressing to soft, normal-colored patches on the upper arms and upper third of the back; they measured approximately 1×2cm2 in size (Fig. 1). She reported no past history of miscarriage, infertility, or vascular thrombosis.

The patient had been referred by the rheumatology department, where she had consulted for dry mouth and dry eyes. Her Schirmer test was positive (3mm in 5 minutes for the right eye and 5 mm in 5 minutes for the left). Sialometry showed low salivary secretion (0.3mL unstimulated and 6.1mL stimulated). Salient analytical findings included the following: anti-nuclear antibody titer, 1/320, with a speckled pattern; anti-Ro/SS-A and anti-La/SS-B antibodies; rheumatoid factor, 56IU/mL (reference range, <20IU/mL); complement factor C4, 86.6μg/mL (reference range, 120–360μg/mL); and immunoglobulin M anticardiolipin antibodies, 6.73MPL/mL (reference range, <4.6MPL/mL). Serologic tests for human immunodeficiency virus, anti-beta-2-glycoprotein i antibodies, and lupus anticoagulant were all negative. These findings had led the rheumatology department to a diagnosis of primary Sjögren syndrome; antiphospholipid syndrome and lupus erythematosus were ruled out.

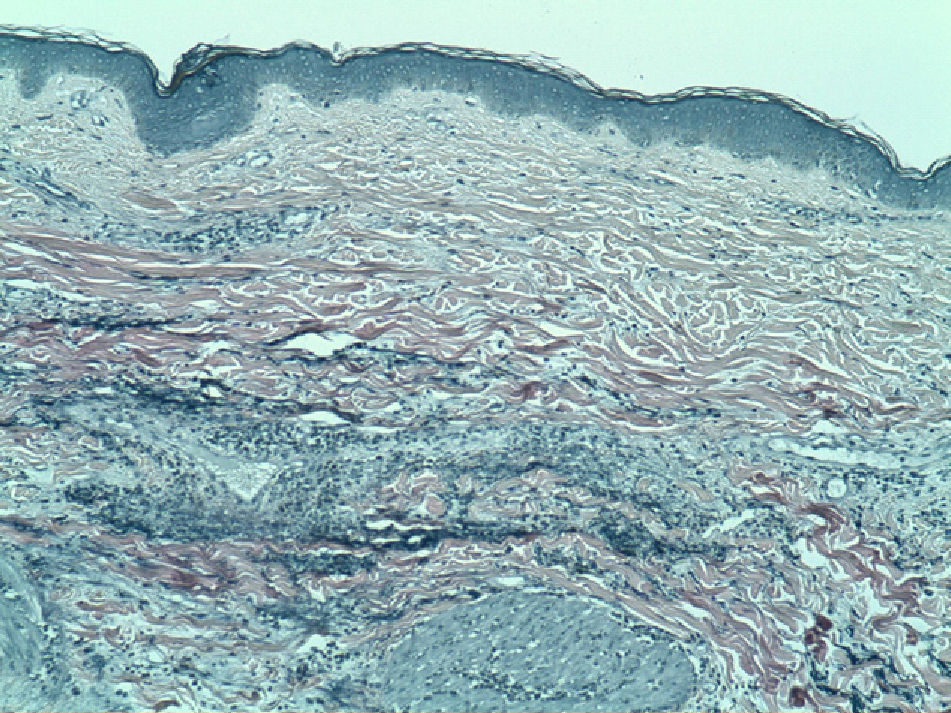

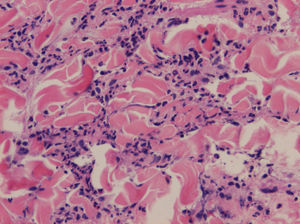

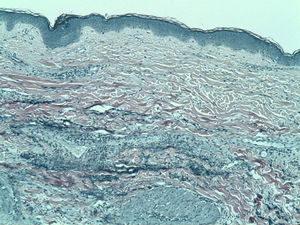

Biopsy of the skin lesions revealed a perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and histiocytes, with abundant neutrophils and eosinophils, in the reticular dermis (Fig. 2). Staining for elastic fibers showed fragmentation and loss of elastic fibers in the papillary and reticular dermis (Fig. 3). These findings led to a diagnosis of primary anetoderma in a patient with primary Sjögren syndrome.

Treatment was started with colchicine (1.5mg/d) and the lesions stabilized; however, treatment was suspended after 2 months due to gastrointestinal intolerance. New, painful erythematous lesions appeared subsequently, and dapsone treatment (50mg/d) was started. This was well tolerated and the dosage was increased to 100mg/d; symptoms improved, and the patient's condition became stable. In December 2011, treatment was discontinued due to paresthesia of the hands. Electromyography findings were compatible with carpal tunnel syndrome, and dapsone-induced neuropathy was thus ruled out. Since no new lesions had developed, treatment was not resumed and the patient was still stable at the time of writing.

Anetoderma is a benign elastolytic disease that primarily affects middle-aged women. Its clinical presentation consists of well-demarcated skin-colored or erythematous papules or plaques, leaving whole areas of wrinkled skin with variable degrees of atrophy and soft herniated areas.1

Histologically, anetoderma is characterized by focal loss of elastic fibers in the reticular dermis and, less frequently, in the papillary dermis. Other common findings include a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, plasma cells, multinucleated giant cells, and exceptionally, eosinophils and neutrophils.2,3

Primary anetoderma appears on clinically normal skin and may be associated with autoimmune disorders, unlike secondary anetoderma, which is linked to other skin conditions such as acne, chicken pox, cutaneous lymphoma, syphilis, and cutaneous lupus erythematosus.4,5 The autoimmune abnormality most frequently associated with primary anetoderma is the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, with or without associated antiphospholipid syndrome.6 Other associations, in descending order of frequency, include systemic lupus erythematosus, alopecia areata, vitiligo, hypothyroidism,4 or analytical abnormalities, such as antinuclear or antithyroid antibodies, or hypocomplementemia.4,5 Primary anetoderma is in fact viewed by some as a marker of autoimmune disease that requires a comprehensive workup for immune disorders.3-6 A recently published case also describes an association of mid-dermal elastolysis, another elastolytic condition, with the presence of autoantibodies, specifically antiphospholipid antibodies.7

The association of primary anetoderma with primary Sjögren syndrome is exceptional, with only 2 cases described in the literature,4,8 although there is 1 published case of anetoderma secondary to multiple plasmocytomas in a patient with Sjögren syndrome.9 Anticardiolipin antibody positivity was not reported in any of these cases.

Several hypotheses are under consideration for the pathogenesis of primary anetoderma. One possibility is that it involves local ischemia caused by microthrombosis, vasculitis, or immune deposits (chiefly immunoglobulin M and complement factor C3) on vessel walls, giving rise to the degeneration of dermal elastic tissue.3,5 Another hypothesis is that neutrophils in the infiltrate alter elastin by secreting elastases, although the role antiphospholipid antibodies might play is unknown.10 No effective treatment has been described for primary anetoderma, but reported findings suggest that neutrophil chemotactic inhibitors such as dapsone or colchicine might be of some use. Braun et al.11 described the stabilization of this condition with colchicine whereas Venencie et al.1 found no improvement using dapsone.

We have presented the first case of primary anetoderma associated with both primary Sjögren syndrome and anticardiolipin antibodies. The presence of Sjögren syndrome together with these antibodies, even at low titers (levels >40MPL/mL are considered moderate to high) further supports the link between primary anetoderma and autoimmune disorders. We also highlight the presence of granulocytes in anetoderma in this case, not only because this unusual finding requires staining for elastic fibers to confirm the diagnosis, but also because patients like ours might benefit from drugs such as dapsone or colchicine.

Please cite this article as: Yélamos O, Barnadas MA, Díaz C, Puig L. Anetodermia primaria asociada a síndrome de Sjögren primario y anticuerpos anticardiolipina. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:99–101.