There is currently little information available on the management of patients with psoriasis in the routine clinical practice of dermatologists in Spain.

ObjectiveThe aim of this study was to survey a group of Spanish dermatologists with particular expertise in the management of psoriasis to determine their opinions on the protocols used in routine clinical practice.

Material and methodsA cross-sectional study based on an online survey about the management of psoriasis sent to 75 dermatologists. The survey, which was specifically designed for the study, included 12questions on different aspects of clinical practice in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis.

ResultsThe response rate was 96% (n=72). Biologics were the most widely used monotherapy option. In total, 64.3% of respondents reported that their patients used conventional systemic therapies for 1 to 2years before switching to a biologic drug and that the main reason for the switch was unstable control of disease activity. Overall, 85.7% assigned “high” or “very high” importance to the use of a Psoriasis Area Severity Index score of <3 as a treatment goal. The drugs of choice among the respondents were etanercept for pediatric patients (78.6%), adalimumab and etanercept for patients with psoriatic arthritis (64.3%), and ustekinumab in patients frequently away from home (78.6%) and patients with a history of multiple sclerosis, demyelinating diseases (64.3%), or poor adherence to treatment (71.4%).

ConclusionThis study provides a unique overview of the opinions of a representative sample of expert dermatologists on the current use of biologics for the treatment of psoriasis in Spain.

En España existe actualmente escasa información sobre el manejo de los pacientes con psoriasis en la práctica clínica diaria de los dermatólogos.

ObjetivoEl objetivo de esta encuesta de opinión fue recoger información de los dermatólogos españoles expertos en el manejo de los pacientes con psoriasis sobre los protocolos que realizan en su práctica clínica habitual.

Material y métodosEncuesta de opinión realizada mediante cuestionario on line remitido a 75 dermatólogos expertos en el manejo de la psoriasis. El cuestionario, diseñado específicamente para la encuesta de opinión, incluía 12preguntas sobre diferentes aspectos de la práctica clínica en el tratamiento de la psoriasis moderada-grave.

ResultadosLa tasa de respuesta fue del 96% (n=72). Los biológicos fueron la opción más usada como monoterapia. El 64,3% de los encuestados señaló que sus pacientes permanecen 1-2años con terapias sistémicas clásicas antes de la transición a biológicos, y el principal determinante para decidir la transición fue el control inestable de la actividad de la enfermedad. El 85,7% dio importancia «alta» o «muy alta» a considerar una puntuación PASI <3 como objetivo terapéutico. Los fármacos de elección más consensuados fueron etanercept en población pediátrica (78,6%), adalimumab y etanercept en artritis psoriásica (64,3%) y ustekinumab en pacientes con frecuentes ausencias domiciliarias (78,6%), baja adherencia (71,4%) e historia de esclerosis múltiple o enfermedades desmielinizantes (64,3%).

ConclusiónEsta encuesta de opinión proporciona una perspectiva única sobre las opiniones de una muestra representativa de los dermatólogos expertos en cuanto al tratamiento actual de la psoriasis con fármacos biológicos en España.

Psoriasis is a chronic, recurring skin disease that affects 2.3% of the Spanish population1 and has been linked in recent years to various other diseases, most notably arthritis. As a result, psoriasis has come to be viewed as a systemic disease in which cutaneous manifestations predominate2 and patient characteristics must be taken into consideration ensure that treatment is appropriate.3–5

More treatment options have become available with the introduction of biologic agents, which generally give better results than traditional systemic drugs and which do not have organ-specific toxic effects. Biologics have therefore changed expectations and treatment goals in moderate to severe disease.6 Clinical practice guidelines and consensus papers aim to provide dermatologists with a range of recommendations they can rely on in routine practice.3,5–8 However, information is still too incomplete or contradictory to help with decisions about certain aspects of treatment.

We currently have little information on how biologics are being used to manage moderate to severe psoriasis in actual clinical situations in Spain. Likewise, we do not know how well dermatologists adhere to recommendations published in the various Spanish3,4,9 and European10,11 guidelines.

The main purposes of this opinion survey were to describe the prescribing criteria followed by Spanish dermatologists who are experts in managing moderate to severe psoriasis, to evaluate Spanish clinical practices applied in various scenarios and types of patients, and to analyze whether or not our practitioners’ preferences are consistent with up-to-date guidelines.

Material and MethodsTarget Population and SettingWe developed an online survey to distribute to a maximum of 75 Spanish dermatologists with recognized experience in managing moderate to severe psoriasis. We targeted practitioners working in hospitals located throughout Spain.

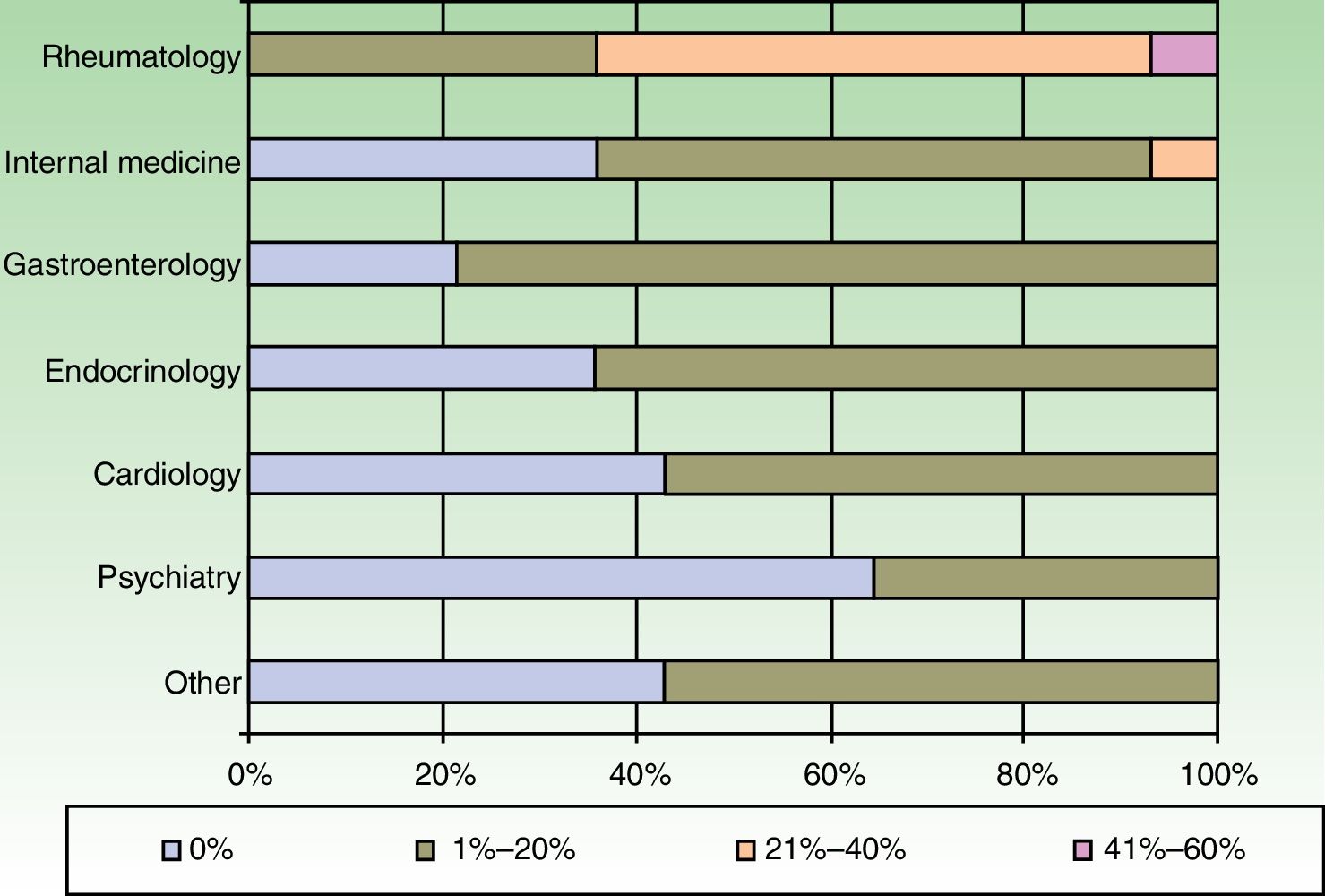

Questionnaire DesignTwo Spanish coordinators collaborated to produce a 12-item questionnaire (Table 1) specifically for this study. The items, which all had closed or numerical answers, covered 4 basic areas: a)current management of moderate to severe psoriasis in clinical practice; b)transitioning from traditional systemic drugs to biologics; c)aspects of management of patients on biologic treatments, and d)assessments of first-line biologic agents according to different profiles of patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Responses to items 4, 9, 10, and 11 were given on a Likert-type scale from1 (least important) to5 (most important). Item 12, in which respondents ranked biologic agents as candidates for use in various types of patients, was also answered on a Likert-type scale—from 1(worst choice) to5 (best choice). The survey was sent to the dermatologists in October 2015 and data were collected for analysis in May and June 2016. The findings were used to draft a report of expert opinion across Spain.

Survey Questionnairea

| Current clinical management of moderate to severe psoriasis |

| 1. Indicate what percentage of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis you manage only with each of the following treatments (monotherapy): |

| a) Topical treatments |

| b) Phototherapy |

| c) Traditional systemic therapy |

| d) Biologics |

| 2. Indicate what percentages of your moderate to severe psoriasis patients on biologics are taking each of the following agents: |

| a) Etanercept |

| b) Adalimumab |

| c) Infliximab |

| d) Ustekinumab |

| e) Secukinumab |

| f) Apremilast |

| Transitioning from a systemic to a biologic treatment |

| 3. Do you think that 2 or 3 traditional systemic therapies or phototherapies should have failed before a patient transitions to a biologic? |

| a) Yes |

| b) No |

| c) Don’t know/no response |

4. Evaluate on a scale of 1 (least important) to 5 (most important) how much you would be influenced by each of the following factors when deciding how long a patient should stay on traditional systemic therapy: |

| a) High doses are needed to control disease. |

| b) Unstable control of disease activity |

| c) Obesity |

| d) Advanced age |

| e) Childbearing age |

| f) Presence of cardiovascular, endocrine or metabolic conditions |

| g) History of neoplastic disease |

5. Indicate how long you generally keep your patients on traditional systemic therapy before transitioning to a biologic: |

| a) 0–6 months |

| b) 6 months–1 year |

| c) 1–2 years |

| d) >2 years |

| Managing treatment in the patient on biologics |

| 6. Once biologic treatment has started, how often do you order follow-up testing? |

| a) Every 3months |

| b) Every 6 months |

| c) Yearly |

| d) Every 2–3years |

| e) Only when risk is suspected |

7. Once biologic treatment has started, how often do you screen for latent tuberculosis infection? |

| a) Only on starting treatment |

| b) Yearly |

| c) Every 2–3years |

| d) Only in patients with risk factors |

8. Indicate the percentage of patients on biologics you refer to specialists in each of the following departments every year on average: |

| a) Internal medicine |

| b) Gastroenterology |

| c) Cardiology |

| d) Endocrinology |

| e) Psychiatry |

| f) Rheumatology |

| g) Other |

| Aims of biologic therapy |

| 9. Rank the importance you place on the following criteria when managing psoriatic skin lesions in patients on biologics. Scale: 1 (least important) to 5 (most important): |

| a) 75% improvement in PASI score |

| b) 90%–100% improvement in PASI score |

| c) PASI score <5 |

| d) PASI score <3 |

| e) PGA, 2-point improvement |

| f) PGA score, 0/1 |

| g) DLQI <5 |

| h) Clinical assessment without a scale |

| i) Patient satisfaction |

10. Rank how important you consider the following criteria when deciding to start a patient with psoriasis on biologic therapy. Scale: 1 (least important) to 5 (most important): |

| a) PASI score >10 |

| b) Extensive skin involvement: >10% BSA |

| c) Significant impact on quality of life (DLQI >10) |

| d) Psoriatic arthritis |

| e) Localized psoriasis with nail involvement |

| f) Localized psoriasis involving highly visible zones |

| g) Cost of treatment |

| h) Patient preference |

11. Rank the importance of the factors you take into consideration when judging whether a patient on biologic therapy is experiencing failure and needs to be switched to another treatment. Scale: 1 (least important) to 5 (most important). |

| a) Loss of response (50% change in PASI score) |

| b) Loss of response (75% change in PASI score) |

| c) Loss of response (90% change in PASI score) |

| d) PASI score >3 |

| e) PASI score >5 |

| f) PGA score >2 |

| g) PGA score >3 |

| h) DLQI >5 |

| Selection of a biologic agent according to patient profile |

| 12. Rank the available biologics on a scale of 1 (worst choice) to 5 (best choice). |

| a) In children and adolescents aged under 18 years |

| b) In women of childbearing age who are considering pregnancy in the medium term |

| c) In adults of advanced age (≥65 years) |

| d) In obese patients (body mass index >30 or weight >90kg |

| e) In patients with psoriatic arthritis |

| f) In patients with a history of multiple sclerosis or demyelinating disease |

| g) In patients with a history of lupus erythematosus or other autoimmune diseases |

| h) In patients with renal insufficiency |

| i) In patients with metabolic syndrome |

| j) In patients with congestive heart failure, grades III–IV |

| k) In patients with a history of stroke |

| l) In patients with latent tuberculosis diagnosed by Mantoux skin test or interferon-γ release assay |

| m) In patients with chronic hepatitisC infection |

| n) In patients with chronic hepatitisB infection |

| o) In patients with chronic human immunodeficiency virus infection |

| p) In patients with depression |

| q) In patients with a history of neoplastic disease |

| r) In patients with an erythrodermic episode |

| s) In patients with unstable disease and frequent exacerbations |

| t) In patients with localized diseases (nail/entheses involvement) |

| u) In patients with scalp psoriasis |

| v) In patients with poor adherence to treatment |

| w) In patients who travel from home often |

| x) In patients who ask for treatment interruptions |

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PGA, Physician's Global Assessment.

The following statistics were compiled for quantitative variables: number of available responses, number of unavailable responses, mean (SD) evaluations and 95%CI of the mean, median (interquartile range), and highest and lowest evaluations (range of responses on the scale). Qualitative variables were described as frequencies and percentages.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the RespondentsThree of the 75 invited dermatologists did not respond (response rate, 96.0%). The respondents were distributed across Spain as follows: southern Spain (n=16); central Spain and the Canary Islands (n=17); northern Spain (n=12); Catalonia (n=15); and eastern coastal Spain (the Levant region) and the Balearic Islands (n=12). Thirty-three of the 72 respondents were men (45.8%) and 39 were women (54.2%).

All were specialists who worked in hospitals in Spain's national public health system.

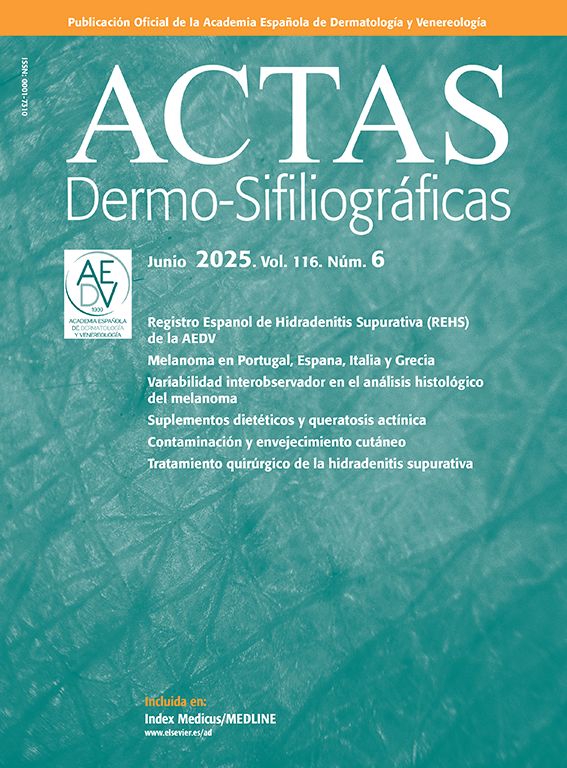

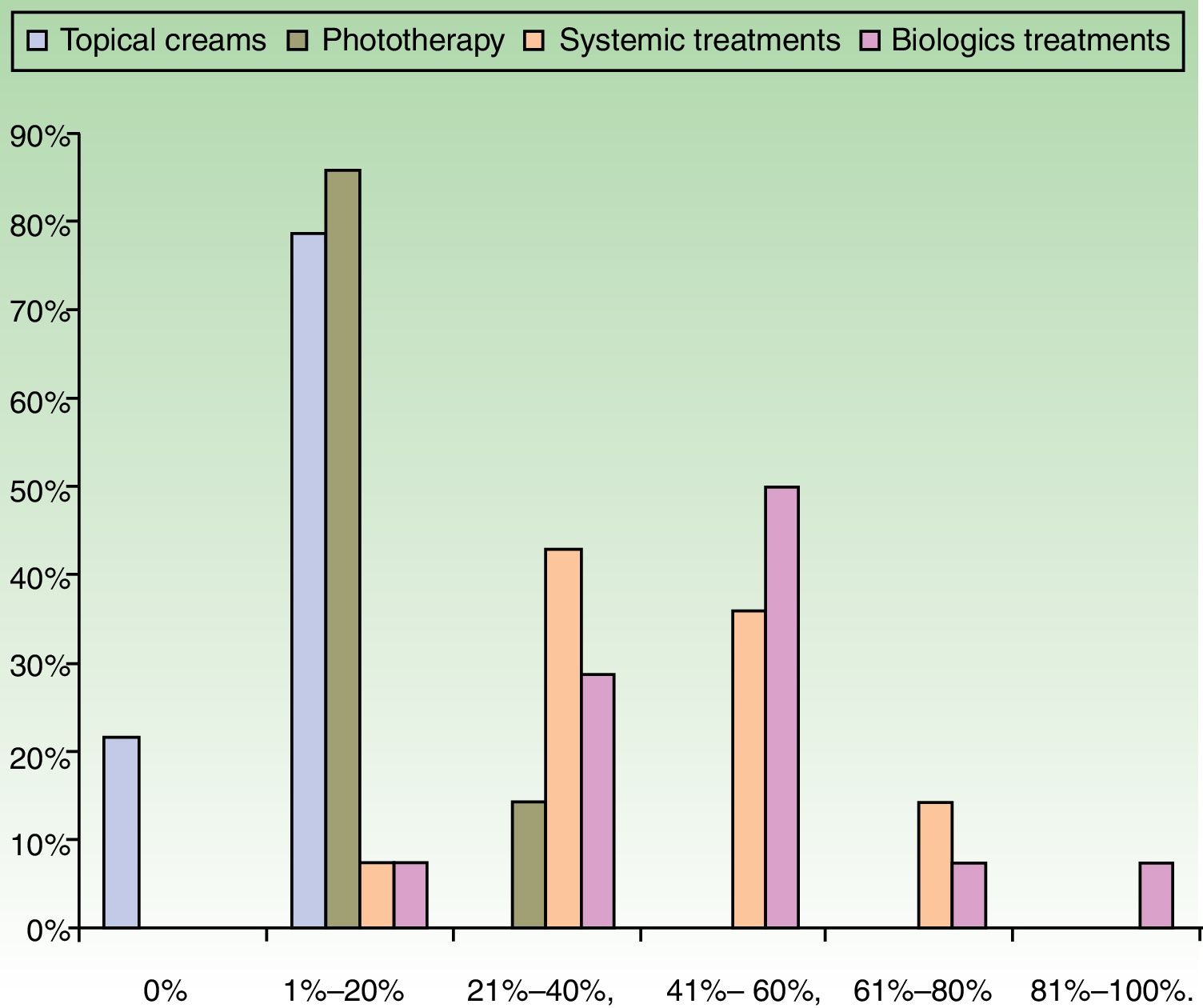

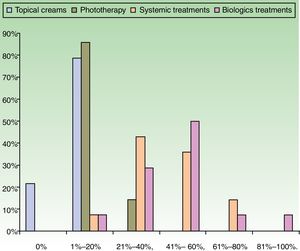

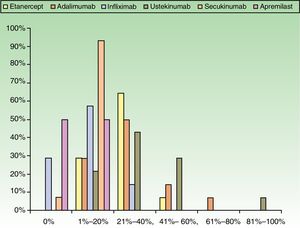

ResultsUse of Traditional Systemic Drugs and Transitioning to Biologic TherapyAnswers to the first survey question, about the percentage of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis being managed with a single therapy, showed that biologics were the most widely accepted choice, ranking ahead of traditional systemic drugs (Fig. 1). Ustekinumab was the biologic agent most prescribed by the largest group of respondents; the next most often prescribed were adalimumab and etanercept (Fig. 2).

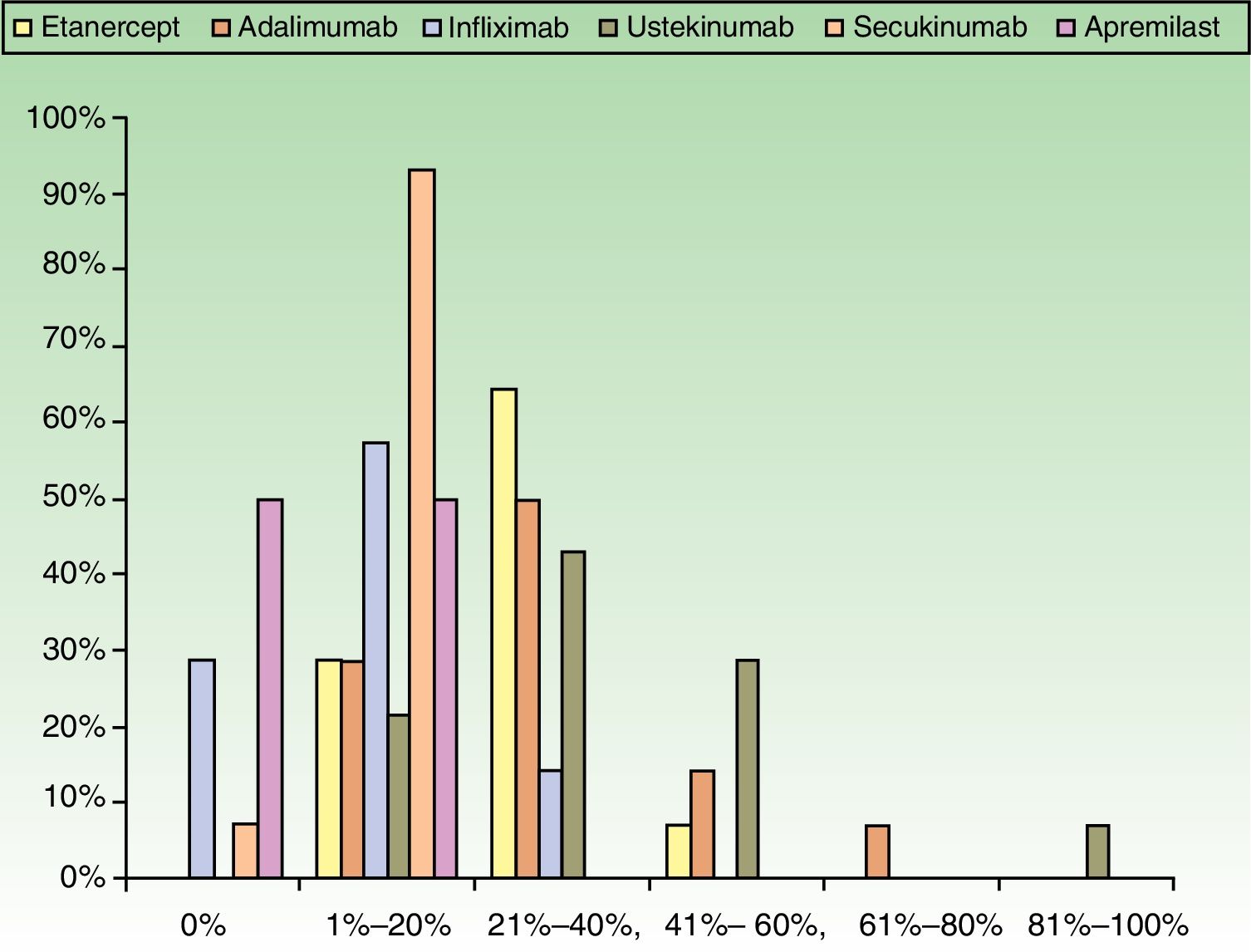

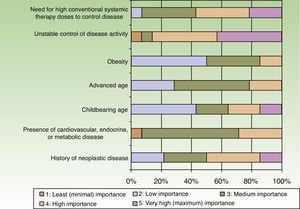

When the respondents considered transitioning a patient from a traditional systemic to a biologic therapy, 35.7% thought that at least 2or 3conventional systemic alternatives or phototherapy should have failed, whereas 64.3% did not share that opinion. The main reason for transitioning to a biologic was unstable disease activity. The second most important reason was that high doses of a conventional systemic therapy were required to control symptoms (Fig. 3).

Patients stayed on conventional systemic treatments for 1to 2years before transitioning to a biologic according to 64.3% of the dermatologists and for 6months to a year according to 21.4%. Only 14.3% reported that patients were kept on traditional systemic therapies for more than 2years.

Biologic TherapiesManaging a Patient's Biologic TreatmentOnce a patient has begun to take a biologic agent, 43.5% of the respondents reported that they order tests to monitor therapy every 3months and another 43.5% test every 6months. Yearly tests are ordered by 4.3%, while another 4.3% test every 2to 3years and yet another 4.3% order tests only when clinical manifestations raise suspicion. Half the respondents test for latent tuberculosis only when starting treatment, 21.4% do so annually, and 28.6% test every 2to 3years.

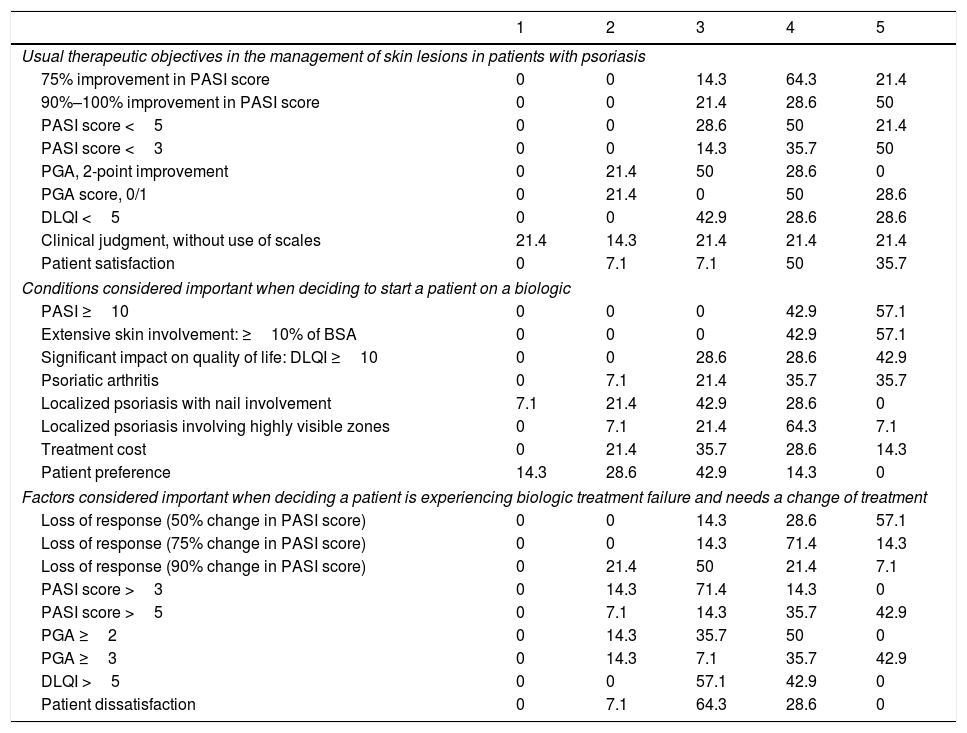

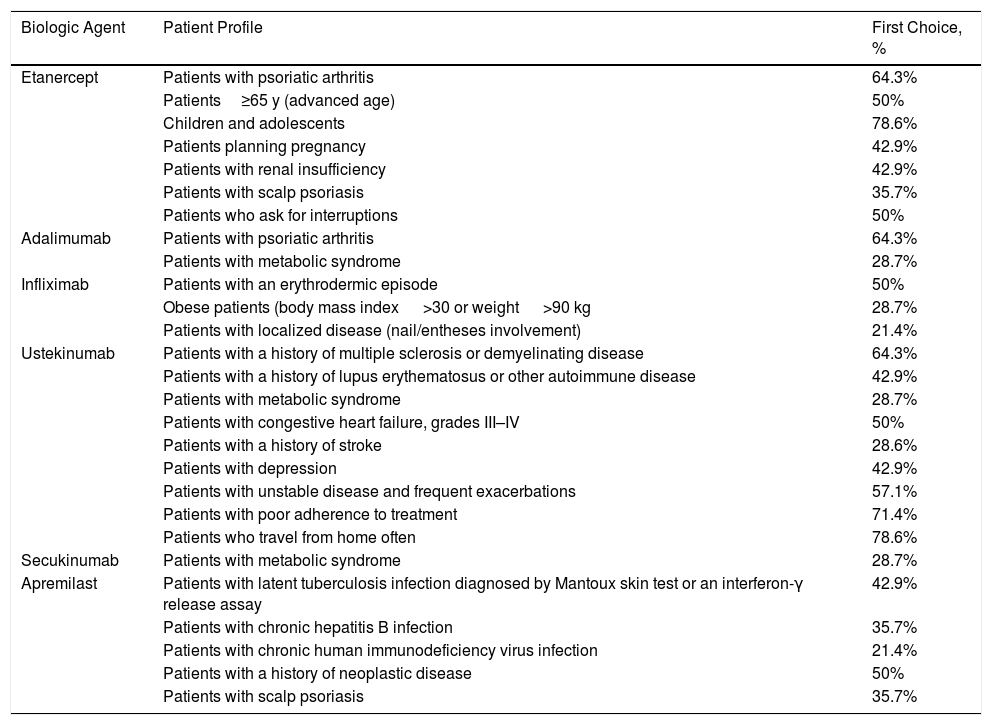

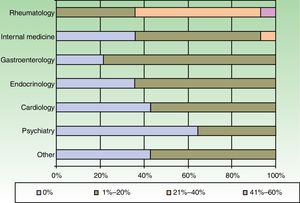

The dermatologists refer their patients to other specialists for evaluation of concurrent conditions (Fig. 4). Referrals were most often to rheumatologists. Referrals to gastroenterologists and endocrinologists were the next most frequent.

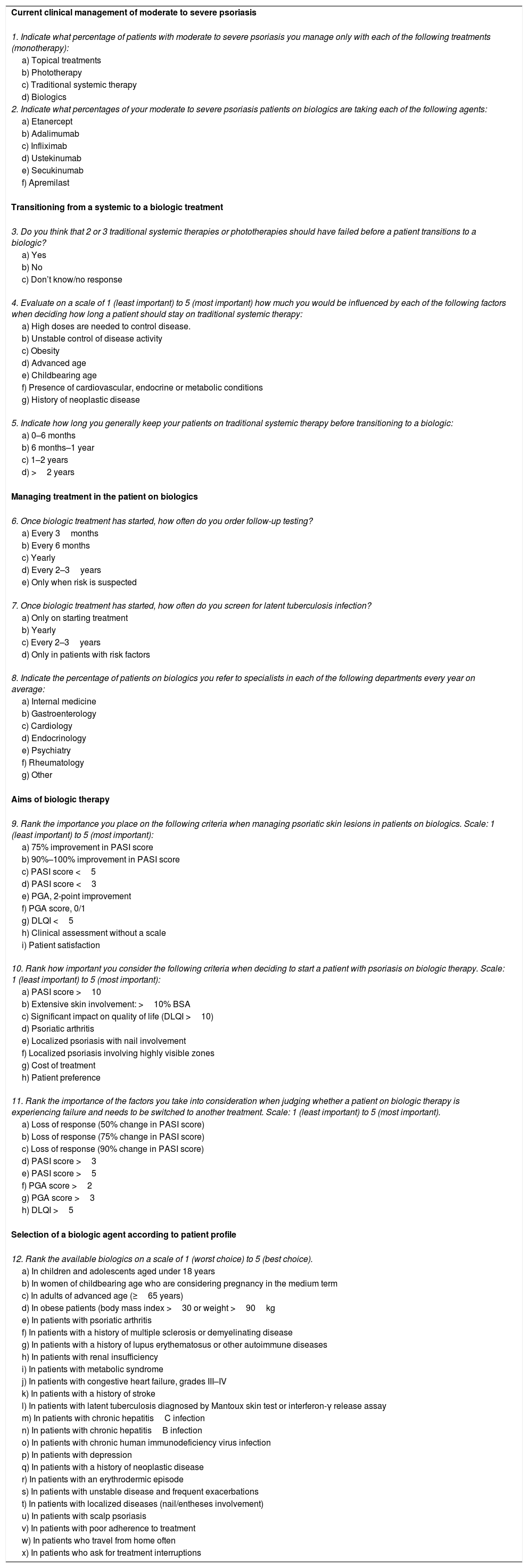

Biologic Treatment ObjectivesTable 2 summarizes the therapeutic objectives the dermatologists prioritize, ranked on a scale of 1 (least important) to 5 (most important). An optimal response of at least 90% improvement in the PASI score was highly valued by 78.6% of the respondents (highly important for 28.6% and very highly important [maximum score] for 50%). Importance was placed on achievement of a PASI score less than 3 by 85.7% (judged highly important by 35.7% and very highly important by 50%). Patient satisfaction was a highly important aim for 50% of the respondents and a very highly important one (maximum score) for 35.7%.

Ranking of Therapeutic Objectives in the Management of Psoriasis a

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual therapeutic objectives in the management of skin lesions in patients with psoriasis | |||||

| 75% improvement in PASI score | 0 | 0 | 14.3 | 64.3 | 21.4 |

| 90%–100% improvement in PASI score | 0 | 0 | 21.4 | 28.6 | 50 |

| PASI score <5 | 0 | 0 | 28.6 | 50 | 21.4 |

| PASI score <3 | 0 | 0 | 14.3 | 35.7 | 50 |

| PGA, 2-point improvement | 0 | 21.4 | 50 | 28.6 | 0 |

| PGA score, 0/1 | 0 | 21.4 | 0 | 50 | 28.6 |

| DLQI <5 | 0 | 0 | 42.9 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Clinical judgment, without use of scales | 21.4 | 14.3 | 21.4 | 21.4 | 21.4 |

| Patient satisfaction | 0 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 50 | 35.7 |

| Conditions considered important when deciding to start a patient on a biologic | |||||

| PASI ≥10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 42.9 | 57.1 |

| Extensive skin involvement: ≥10% of BSA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 42.9 | 57.1 |

| Significant impact on quality of life: DLQI ≥10 | 0 | 0 | 28.6 | 28.6 | 42.9 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 0 | 7.1 | 21.4 | 35.7 | 35.7 |

| Localized psoriasis with nail involvement | 7.1 | 21.4 | 42.9 | 28.6 | 0 |

| Localized psoriasis involving highly visible zones | 0 | 7.1 | 21.4 | 64.3 | 7.1 |

| Treatment cost | 0 | 21.4 | 35.7 | 28.6 | 14.3 |

| Patient preference | 14.3 | 28.6 | 42.9 | 14.3 | 0 |

| Factors considered important when deciding a patient is experiencing biologic treatment failure and needs a change of treatment | |||||

| Loss of response (50% change in PASI score) | 0 | 0 | 14.3 | 28.6 | 57.1 |

| Loss of response (75% change in PASI score) | 0 | 0 | 14.3 | 71.4 | 14.3 |

| Loss of response (90% change in PASI score) | 0 | 21.4 | 50 | 21.4 | 7.1 |

| PASI score >3 | 0 | 14.3 | 71.4 | 14.3 | 0 |

| PASI score >5 | 0 | 7.1 | 14.3 | 35.7 | 42.9 |

| PGA ≥2 | 0 | 14.3 | 35.7 | 50 | 0 |

| PGA ≥3 | 0 | 14.3 | 7.1 | 35.7 | 42.9 |

| DLQI >5 | 0 | 0 | 57.1 | 42.9 | 0 |

| Patient dissatisfaction | 0 | 7.1 | 64.3 | 28.6 | 0 |

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area Severity Index; PGA, Physician Global Assessment.

The conditions considered important when deciding to start treatment with a biologic agent in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis are also summarized in Table 2. All the dermatologists (100%) agreed that a PASI score of 10 or higher and the involvement of over 10% of the body surface area were the important criteria (highly important for 42.9% and very highly important for 57.1%).

Factors Leading to Change of TreatmentThe factors the dermatologists considered important when deciding that a patient was experiencing failure of a biologic therapy and needed to be switched were as follows: loss of response (a 50% to 75% change PASI score), a PASI score greater than 5, or a Physician's Global Assessment score of 3 or more (Table 2).

Biologic of Choice According to Patient ProfileTable 3 summarizes the dermatologists’ ranking of biologic agents according to patient profile on a scale of 1 (worst choice) to 5 (best choice). The preference was most often etanercept (78.6%) for pediatric patients; etanercept (64.3%) or adalimumab (64.3%) for patients with psoriatic arthritis; and ustekinumab for patients who often travel (78.6%), had poor compliance (71.4%), or had a history of multiple sclerosis or demyelinating disease (64.3%).

Biologic of Choice According to Patient Profile.

| Biologic Agent | Patient Profile | First Choice, % |

|---|---|---|

| Etanercept | Patients with psoriatic arthritis | 64.3% |

| Patients≥65 y (advanced age) | 50% | |

| Children and adolescents | 78.6% | |

| Patients planning pregnancy | 42.9% | |

| Patients with renal insufficiency | 42.9% | |

| Patients with scalp psoriasis | 35.7% | |

| Patients who ask for interruptions | 50% | |

| Adalimumab | Patients with psoriatic arthritis | 64.3% |

| Patients with metabolic syndrome | 28.7% | |

| Infliximab | Patients with an erythrodermic episode | 50% |

| Obese patients (body mass index >30 or weight >90 kg | 28.7% | |

| Patients with localized disease (nail/entheses involvement) | 21.4% | |

| Ustekinumab | Patients with a history of multiple sclerosis or demyelinating disease | 64.3% |

| Patients with a history of lupus erythematosus or other autoimmune disease | 42.9% | |

| Patients with metabolic syndrome | 28.7% | |

| Patients with congestive heart failure, grades III–IV | 50% | |

| Patients with a history of stroke | 28.6% | |

| Patients with depression | 42.9% | |

| Patients with unstable disease and frequent exacerbations | 57.1% | |

| Patients with poor adherence to treatment | 71.4% | |

| Patients who travel from home often | 78.6% | |

| Secukinumab | Patients with metabolic syndrome | 28.7% |

| Apremilast | Patients with latent tuberculosis infection diagnosed by Mantoux skin test or an interferon-γ release assay | 42.9% |

| Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection | 35.7% | |

| Patients with chronic human immunodeficiency virus infection | 21.4% | |

| Patients with a history of neoplastic disease | 50% | |

| Patients with scalp psoriasis | 35.7% |

Half the respondents (50%) also thought that ustekinumab was the best choice for patients with grade III to IV congestive heart failure.

In patients at risk for exacerbation of latent infection, apremilast (first choice) and etanercept (second choice) were thought to be the most appropriate biologics. Apremilast was preferred for patients with chronic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection by 42.8% of the respondents, 21.4% considering it the best choice and 21.4% a good choice. However half the respondents (50%) considered etanercept to be the best (14.3%) or a good (35.7%) choice for such patients.

DiscussionAn increasing number of publications have been based on surveys of dermatologists’ use of treatments for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, probably in an attempt to promote consistent clinical practice and optimize treatment.

This opinion survey aimed to ascertain the real situation of routine management of moderate to severe psoriasis in Spain by describing the preferences of Spanish dermatologists expert in this disease. The results allow us to analyze whether their preferences are in keeping with current Spanish and European practice guidelines. The survey also covered complex scenarios in which optimal treatment is not well defined because firmly evidence-based clinical protocols are not yet available.

The efficacy and safety of biologic treatments, and their superiority over traditional systemic treatments, have become increasingly clear,12 leading to wider use of biologics in Spain.13 Monotherapy based on these drugs is being prescribed to an ever greater percentage of patients with moderate to severe disease.

Transition to BiologicsOur data show that dermatologists are now keeping patients on conventional systemic treatments for less time than was reported in 2013 based on an online survey of members of the Psoriasis Working Group (PsWG) of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV).14 Prescribers are also currently more likely to transition patients with unstable disease from traditional systemic therapy to biologics in order to optimize treatment. The 2013 report found that 73% of respondents waited 2or more years to switch patients away from a traditional systemic treatment to a biologic, even though a considerable percentage (66%) thought the wait should be shorter. Our survey results suggest that Spanish practice is changing, as only 14.3% of patients now stay on conventional treatment for 2years. The consensus statement of the PsWG published in 2016 even reported the opinion that biologics should be considered first-line options for treating moderate to severe psoriasis, alongside conventional systemics.9

Change is also evident in the criteria dermatologists use to shorten the transition period. Toxic effects of systemic treatment once reigned as the main criterion, whereas loss of response or possible unevenness of response are now main concerns. The experts continue to take scant account of concomitant conditions when making this decision.

Management of Therapy for Patients on BiologicsMost respondents order tests every 3to 6months, as advised by the UK's National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).15 There is considerable variation in tuberculosis screening practices. Screening only at the start of biologic treatment is the approach that predominates,16 even though the Spanish PsWG's 2016 consensus statement9 recommends repeated screening while the patient is on such therapy. However, consensus for that statement was reached in 2012 and 2013, several years before the 2016 publication date. The results of the present survey, therefore, reflect the more up-to-date clinical practice opinions of dermatologists.

Criteria That Lead Specialists to Recommend Biologic TherapyThe dermatologists surveyed considered the following criteria to be important when deciding to recommend biologic therapy: PASI score≥10 or an affected body surface area of at least 5% to 10%; patient perception of having severe disease (Dermatology Life Quality Index>10); and the presence of psoriatic arthritis, consistent with an earlier PsWG consensus statement.6

Therapeutic ObjectivesThe introduction of biologic drugs in clinical practice has improved the efficacy of psoriasis treatment, as shown by the opinion of 78.6% of our respondents that treatment should achieve at least a 90% improvement in the PASI score—the equivalent of an absence of clinical signs (clearing) or minimal signs of disease—or even that a PASI score of 3 or less should be sought. These goals are much more ambitious than the therapeutic objectives suggested by previously published guidelines, which recommend seeking 75% of more improvement in the score. The response criterion of 90% improvement also offers a more discriminating objective in terms of bettering patients’ quality of life17 than the lower goal of a 75% change in PASI score.

Individualized TreatmentIn clinical scenarios in which there is still no firm evidence to guide the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis, therapy must be tailored to the patient's situation.5 The prescriber must therefore apply criteria based on experience gained by experts during routine clinical practice. Our survey, which provides data on the main criteria used by Spanish dermatologists when choosing a biologic, sheds light on practice in such scenarios.

Most respondents chose etanercept for pediatric patients (78.6%); adalimumab or etanercept for patients who also have psoriatic arthritis (64.3%); and ustekinumab for patients who have to travel away from home often (78.6%), whose adherence is poor (71.4%), or who have a history of multiple sclerosis or demyelinating disease (64.3%). The first-choice biologics for other scenarios varied greatly.

Some of these findings are consistent with opinions reported previously14 or with some guidelines.11 Our informants, all experts in psoriasis, expressed the novel opinions that secukinumab would be one of the biologics of choice for patients who are obese or have metabolic syndrome and that apremilast would be a good choice for patients with a history of neoplastic disease, chronic infection, or latent tuberculosis.

Warnings and contraindications are important to consider when choosing a biologic. The panel named ustekinumab, of which a maintenance dose is taken every 12weeks, as appropriate for scenarios in which there are adherence problems. It was also considered a candidate for scenarios in which anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy is contraindicated (lupus erythematous and other autoimmune diseases, advanced heart failure, and demyelinating diseases), a suggestion that has been noted in the literature.18

Children and AdolescentsEtanercept was chosen as the first-line biologic for pediatric populations. The respondents’ choice could be explained by the fact that etanercept was the first biologic approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of chronic severe plaque psoriasis in children aged 6years or older.19 Alternative explanations are that etanercept is the biologic agent that has been most widely studied in randomized clinical trials in children and adolescents20 to date, and it is the only one for which long-term extension studies have been carried out.21

Other biologics have begun to be subjected to such study. Examples are adalimumab, recently approved by the EMA for pediatric use and the subject of a trial in children and adolescents22 and ustekinumab.23 The range of treatments available for pediatric use is increasing.

Advanced AgePreviously published guidelines for treating patients aged 65years or older recommend prioritizing safety, suggesting intermittent treatment approaches and lower doses than those listed in product summaries.24 The group of experts we surveyed chose etanercept as their first choice, presumably because of its short half-life, good safety and efficacy profiles,25 and tolerance in patients of advanced age.26 Recently published Italian guidelines point out that any of the biologics could possibly be used in this population if patients are monitored adequately, since few studies of adalimumab, etanercept, and ustekinumab in the elderly have as yet appeared.27,28

Risk of Infection and Reactivation of InfectionThe risk of reactivation of latent infection or of opportunistic or serious infection is lower in patients with psoriasis than in those with other inflammatory diseases because psoriasis patients have different characteristics and are not usually on additional immunosuppressant therapies. However, risk is slightly higher in patients on infliximab or adalimumab than in those on etanercept or ustekinumab.29 The recommendations published by the AEDV's PsWG9 and the Italian group11 suggest that the risk of reactivation is lower with etanercept, based on wider experience using that biologic in patients with chronic hepatitis C and HIV infections.30,31 However, for this scenario our surveyed experts selected apremilast, an oral biologic agent that has lower efficacy but that seemed to have less of an immunosuppressant effect in a recent trial.32

Psoriatic ArthritisThe association of arthritis and psoriasis affects the choice of biologic, and guidelines recommend the use of an anti-TNF agent as the first line of therapy. These drugs have demonstrated efficacy in the 5key domains of this scenario: 1) peripheral arthritis; 2) skin and nail lesions; and the involvement of 3) axillas, 4) joints of fingers or toes (dactylitis), and 5) entheses (evidence level 1+).33 Anti-TNF agents have also been shown to inhibit the radiologic progression of psoriatic arthritis.34,35 Our respondents’ opinion that etanercept and adalimumab were the best choices could be due to reports of superior cost-effectiveness.36 However, it is important to also bear in mind that when we collected data for this analysis (in May–June 2016) the experts had not yet accumulated much experience with new biologics, especially secukinumab, in psoriatic arthritis. That drug is a well placed candidate at present, given the observation of good results at even lower doses than those generally used in psoriasis (see the FUTURE137 and FUTURE238 studies).

Congestive Heart FailureAnti-TNF agents are contraindicated in patients with congestive heart failure (gradesIII–IV). In patients with this concomitant condition ustekinumab could be considered the treatment of choice.

Intermittent Treatment RegimensThe Spanish dermatologists who responded to our survey preferred etanercept for intermittent treatment regimens, consistent with another survey14 and European guidelines.11 Their choice could be due to the pharmacokinetic characteristics of this drug, which has a shorter half-life and has proven effective in intermittent protocols and retreatments without causing additional adverse events.39,40

Difficult Disease LocationsRecently published Spanish guidelines point to the difficulty of managing psoriasis in certain locations—such as the scalp, nails, palms, and plantar surfaces—and the scarcity of well organized information and high levels of evidence about such treatment difficulties.41 Guidelines on the use of biologics in patients with psoriasis in difficult-to-treat locations published in 2015 named infliximab and etanercept as good choices in scalp psoriasis (grade A recommendation, evidence level 1). The strength of recommendation is lower for adalimumab (grade B, level-1 evidence) and lower still for ustekinumab (grade C, level-1 evidence).8 The ESTEEM1 and 2trials recently demonstrated the efficacy of apremilast in these types of psoriasis,42 and the GESTURE trial concluded that secukinumab was very effective in the treatment of palmar-plantar psoriasis.43

ObesityObesity plays a role in response to all biologic therapies, although differences often fail to reach statistical significance. The possibility of adjusting the dosage of infliximab according to weight offers the opportunity to achieve similar results in obese and nonobese patients.44

PregnancyTailored management is important in women who are pregnant or planning pregnancy, when the drug's half-life and the severity of disease must be weighed in the balance. Biologics used to treat psoriasis are categoryB drugs. In fact, a biologic's average half-life must be factored in whenever a woman of childbearing age is treated. Etanercept has the shortest half-life (3days), infliximab the next shortest (10days), followed by adalimumab (15days) and ustekinumab (3weeks). Contraceptives are recommended during treatment and up to 3weeks after suspending treatment with etanercept, 15weeks after stopping ustekinumab, 5months after stopping adalimumab, and 6months after stopping infliximab.24 Because immunoglobulinG is transported to the fetus during the second and third trimesters, guidelines recommend interrupting treatment with infliximab and adalimumab during the last trimester to prevent neonatal immunosuppression.11 In a case series describing 5pregnant women treated with ustekinumab, 1pregnancy resulted in miscarriage.45

Metabolic SyndromeA high prevalence of metabolic syndrome (14% to 40%) has been reported in psoriasis.46 An underlying inflammatory state is common to both conditions,47 as evidenced by altered levels of secretory proteins such as adponectin and leptin, which regulate the release of such mediators as TNF; interleukins6, 7, and 22; and interferon-γ. Drugs like acitretin, ciclosporin, and methotrexate can aggravate some components of metabolic syndrome, so biologics, which target more specific components of disease, are considered the first line of therapy for patients with this condition.48 Our survey found that the dermatologists’ choices for patients with moderate to severe psoriasis and metabolic syndrome were adalimumab, ustekinumab, and secukinumab.

LimitationsBecause ours was an opinion survey of 73 specialists in different hospitals and geographic areas, the highly variable results must be interpreted with caution. Nonetheless, the findings provide important information that reflects the professional experience and routine clinical practice of dermatologists.

ConclusionsThis opinion survey provides a unique perspective on the views of a representative sample of expert dermatologists regarding the current management of psoriasis with biologics in Spain.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ambos autores son indistintamente primeros autores.

Please cite this article as: López-Estebaranz JL, de la Cueva-Dobao P, Fraga CdlT, Gutiérrez MG, Guerra EG, Sánchez JM, et al. Manejo de la psoriasis moderada-grave en condiciones de práctica habitual en el ámbito hospitalario español. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:631–642.