Contact dermatitis is one of the most common reasons for consultation in dermatology. However, general dermatologists do not always appreciate the importance of patch testing. These tests should ideally be performed in specialist skin allergy units, most importantly in cases suggestive of contact dermatitis, severe acute dermatitis, chronic persistent dermatitis, and dermatitis affecting the eyelids, genital region or adjacent to venous ulcers. Eczematous changes in pre-existing skin lesions or lesions at atypical sites in patients diagnosed with atopic eczema should also be investigated. Finally, cases diagnosed as occupational dermatitis can be best managed by the workers’ health insurance scheme.

La dermatitis de contacto es uno de los motivos de consulta más frecuentes en Dermatología. Sin embargo, la realización de pruebas complementarias, especialmente las pruebas epicutáneas de contacto, puede ser menospreciada por el dermatólogo general. Idealmente la realización de pruebas epicutáneas se debiera realizar en Unidades de referencia de Alergia Cutánea, especialmente en eccemas que delimiten la figura de un contactante, eccemas agudos graves, eccemas crónicos persistentes y los localizados en párpados, área genital o alrededor de úlceras venosas. La eccematización de lesiones cutáneas previas, o la localización atípica de lesiones eccematosas en enfermos diagnosticados de eccemas endógenos también debieran ser estudiadas. Finalmente, aquellas dermatitis catalogadas como enfermedad profesional son manejadas más óptimamente por la mutua laboral propia del trabajador.

Eczema can be classified, generally speaking, as either endogenous or exogenous. The exogenous form, or contact eczema, can be further subdivided into 2 groups according to whether it is of irritant or allergic origin. The management of these 3 types is very different, and patch testing must be undertaken if we seek objective information that rules out or confirms a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis. Either the patient or the physician may consider such tests to be problematic, however.1–3 Although the efficacy and efficiency of patch testing have been clearly demonstrated,4,5 doubts arise when the dermatologist sees patients with eczematous lesions that do not seem to clearly warrant investigation.6 In view of the fact that contact dermatitis accounts for between 4% and 7% of the dermatology caseload,7 this article sets out to explain the criteria for making decisions about referral to a skin allergy unit in a variety of situations.

Benefit and Interest: 2 CriteriaPerforming patch tests or referring a patient to another physician for such testing is a medical act and as such should be guided by the criterion of what is beneficial for the patient. To benefit a person is to do what is good for that person, according to the dictionary of the Royal Spanish Academy.8 However, what is beneficial does not always coincide with the patient's, the physician's, or the health care administrators’ interests. All 3 parties ordinarily share the same goals, but this will not always be the case, particularly in occupational medicine. Some patients receive material benefit from their disease process through compensation when they must leave their jobs or be absent for medical reasons. Others insist on staying in the workplace until they are eligible to receive an adequate retirement pension. An employer or an occupational health insurer may also have interests; likewise, a physician might wish to increase the demand for a contact dermatitis unit or, indeed, minimize the need for one and thus avoid ordering complementary tests for patients with a diagnosis of eczema. In all such situations the criterion of patient benefit must be primordial, taking precedence over the interests of managers, physicians, or even over any nonhealth-related interests the patient might express. This principle can be clarified by examples. Suppose we suspect sensitization to nickel or other metals on the basis of a patient's medical history. Should we order skin allergy tests? If we apply the essential principle of patient benefit, we would place at one extreme a case in which the patient has complained of an unrelated problem but we discover he or she has a history of intolerance to jewelry. Will the patient receive significant benefit from patch testing? At the other extreme would be a patient with an intolerance to jewelry who must undergo a knee arthroplasty procedure in which a metal prosthesis will be implanted. Even though it is highly unlikely that the patient will have a reaction to the alloys used in the device, if one were to occur the resulting harm would be so great that it would be worthwhile performing the tests to have objective information about which metals he or she is sensitized to before the operation.9

Spanish legislation, recorded in the government's Official Gazette, distinguishes common health processes from occupational ones, stating that “the occupational health insurer that manages or collaborates in the protection of occupational health shall write and issue a report to categorize the possible occupational illness.”10 In the case of an occupational dermatitis, the patient's benefit, in terms of optimization of employment and possible future compensation claims, will be more in keeping with current law if he or she is followed by a dermatologist belonging to the occupational health insurance provider. That dermatologist will be responsible for referral to a skin allergy unit according to the criteria discussed in this article. In situations in which patients are not covered by an occupational health insurer the skin allergy units of the National Health Service will take responsibility; examples of such patients would be the unemployed or those in certain occupations in which different types of coverage apply.10

Patch testing is relatively simple and can be carried out with minimal equipment. The risk lies in focusing narrowly on testing for contact dermatitis but not on solving the patient's problem. It would be absurd if the presumed benefit a patient received, after spending 2 days with patches in place and unable to wash the skin on his or her back for 5 days, were only to receive a report that warns against coming into contact with certain substances whose names are often unfamiliar. According to the criterion of acting in the patient's benefit, we should provide a report that includes a diagnosis (eg, allergic contact eczema, irritant dermatitis, dyshidrotic eczema, etc), lists the complementary tests performed, and indicates the significance of the positive results found. We should also note that the patient will remember best what the physician actually says during the interview.11 Determining the relevance of positive results (whether present, past, or uncertain) requires detective work by a dermatologist who has appropriately specific training and whose knowledge is current.3,12–14 If we are working within the Spanish National Health Service, the ideal is to refer patients to dermatology clinics that have skin allergy units with up-to-date information, trained personnel, test batteries with a sufficiently wide range of haptens, and the capacity to test for photoallergy.2,3,6,15 Beyond their purely clinical workload, these units are also able to carry out epidemiologic and other research relevant to the discipline.16 However, according to a white paper on our specialty published by the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV),17 only 50% of public hospitals in Spain have a contact dermatitis unit. We can therefore suppose that many patients do not have access to these tests, whether the reason is the type of care they are given or the application of administrative criteria. In such cases the panel recommended by the Spanish Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy Research Group or the thin-layer rapid-use epicutaneous (TRUE) test panel must suffice. According to Saripalli and coworkers,18 however, the TRUE test of 23 allergens can be considered complete for only 25% of patients being studied. Whenever we are unable to perform a full battery of relevant tests, we must proceed with an open mind, attempting to complete the study with products the patient uses or is exposed to, without closing the case after the final reading of the patch test panel. If we do not proceed in this way, we may convey to patients a false confidence that will not be in their interest.3,19

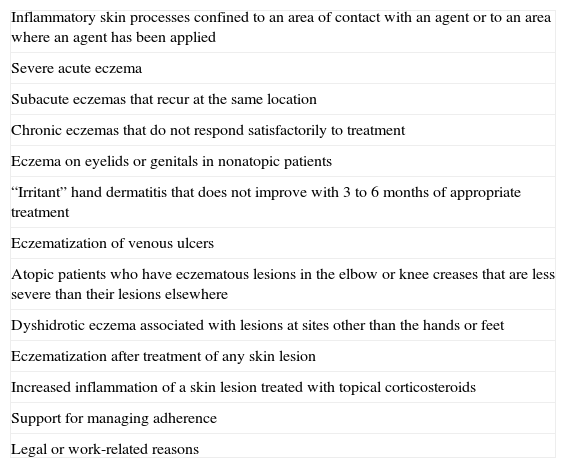

Depending on the reason for referring a patient to a skin allergy unit, the benefit we are seeking to offer may be diagnostic, therapeutic, or legal (Table 1).

Indications for Referral of Patients to a Skin Allergy Unita.

| Inflammatory skin processes confined to an area of contact with an agent or to an area where an agent has been applied |

| Severe acute eczema |

| Subacute eczemas that recur at the same location |

| Chronic eczemas that do not respond satisfactorily to treatment |

| Eczema on eyelids or genitals in nonatopic patients |

| “Irritant” hand dermatitis that does not improve with 3 to 6 months of appropriate treatment |

| Eczematization of venous ulcers |

| Atopic patients who have eczematous lesions in the elbow or knee creases that are less severe than their lesions elsewhere |

| Dyshidrotic eczema associated with lesions at sites other than the hands or feet |

| Eczematization after treatment of any skin lesion |

| Increased inflammation of a skin lesion treated with topical corticosteroids |

| Support for managing adherence |

| Legal or work-related reasons |

The most common reason for sending a patient to a hospital-based contact dermatitis clinic is to reach an etiologic diagnosis that explains the clinical picture, that is, to distinguish between irritant and allergic contact dermatitis and, if the patient's condition is allergic, to determine the allergens causing the reaction and relate the detected sensitizations to the patient's original complaint.14 Expressed in medical terms, one orders tests to determine the main causes of the skin condition, although we should also consider the possibility that a patient's quality of life may even improve after negative results of patch testing.20–22 A final point to remember is that age is not a limiting factor for patch testing. Age only presents logistical problems for performing a complete test battery; examples would be the available body surface area in infants and disability in the elderly.23–26

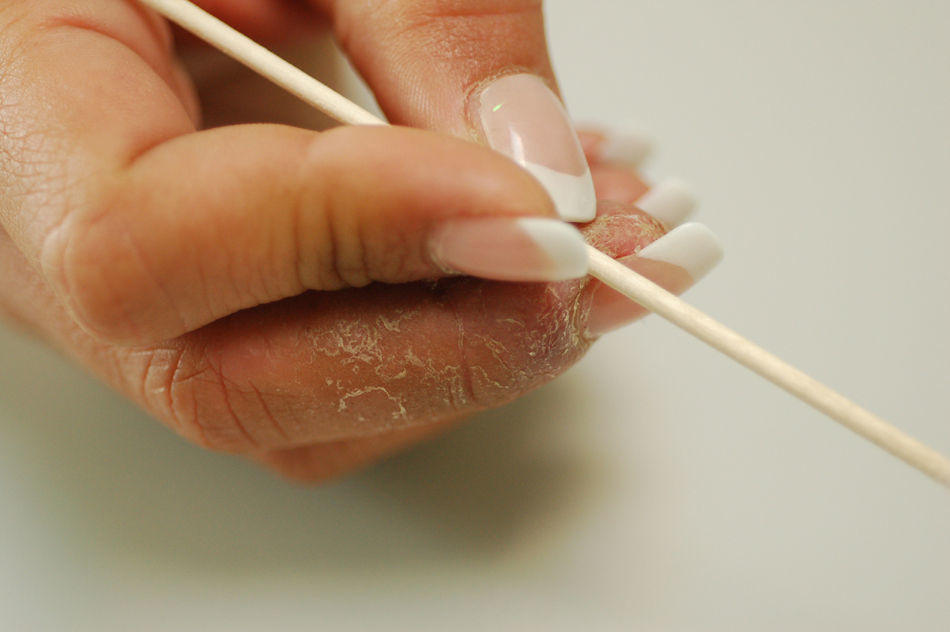

Diagnostic Referral Based on Lesion MorphologyAs the name suggests, contact dermatitis is caused by external substances that come into direct contact with the skin. As a result, the shape of an object whose contact with the skin leads to irritation is often faithfully reflected by the inflamed area (Fig. 1). However, processes other than irritant or allergic contact eczema may also leave a telltale pattern, so each case should be fully assessed in a specialized unit. Among such processes are contact urticaria, contact purpura, some granulomatous reactions,, and some lichenoid lesions (especially those on mucosal surfaces).

Diagnostic Referral Based on Lesion SeverityIf a patient is re-exposed to a substance that previously provoked a severe eczematous reaction, renewed exposure will usually cause an even more intense eruption. Therefore, it is in the patient's best interest to undertake a detailed investigation of potential triggers of contact eczema whenever severe acute reactions have occurred (Fig. 2), with a view to avoidance of re-exposure. In recurring subacute eczematous lesions that are localized and that tend to persist, especially if asymmetrically located on the body, sensitization should always be suspected and adequately investigated. Referral is especially important in such cases because the presentation can mimic that of the initial phase of mycosis fungoides; histologic examination will be necessary.27

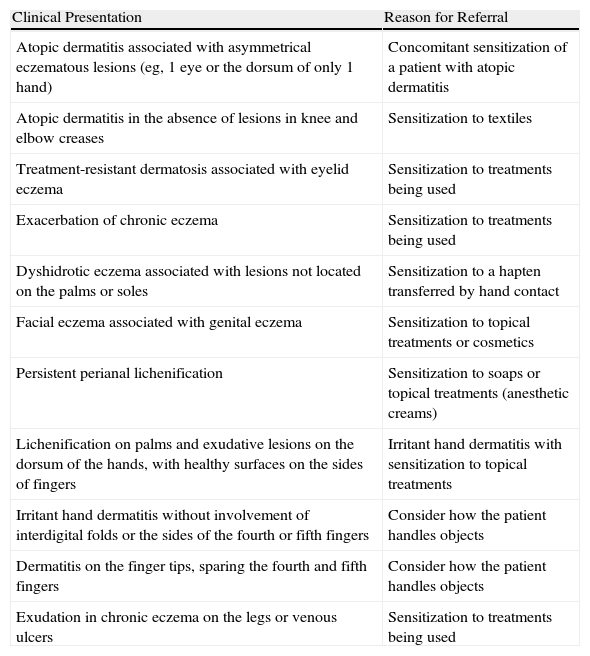

Diagnostic Referral Based on the Location of LesionsAllergic contact dermatitis can appear anywhere on the skin, but the thin stratum corneum of the eyelids make them a particularly vulnerable target. Haptens may be airborne or carried to eyelids on the patient's hands. Therefore, allergic contact dermatitis should be suspected whenever eczematous lesions on any location are found in association with eczema on the eyelids. A similar but less common situation is that of genital eczema in association with other lesions at a distance. Sensitization to topical treatments the patient is using (Table 2) should be suspected when eczema forms on varicose ulcers.6,14

Atypical Chronic Eczemas.

| Clinical Presentation | Reason for Referral |

| Atopic dermatitis associated with asymmetrical eczematous lesions (eg, 1 eye or the dorsum of only 1 hand) | Concomitant sensitization of a patient with atopic dermatitis |

| Atopic dermatitis in the absence of lesions in knee and elbow creases | Sensitization to textiles |

| Treatment-resistant dermatosis associated with eyelid eczema | Sensitization to treatments being used |

| Exacerbation of chronic eczema | Sensitization to treatments being used |

| Dyshidrotic eczema associated with lesions not located on the palms or soles | Sensitization to a hapten transferred by hand contact |

| Facial eczema associated with genital eczema | Sensitization to topical treatments or cosmetics |

| Persistent perianal lichenification | Sensitization to soaps or topical treatments (anesthetic creams) |

| Lichenification on palms and exudative lesions on the dorsum of the hands, with healthy surfaces on the sides of fingers | Irritant hand dermatitis with sensitization to topical treatments |

| Irritant hand dermatitis without involvement of interdigital folds or the sides of the fourth or fifth fingers | Consider how the patient handles objects |

| Dermatitis on the finger tips, sparing the fourth and fifth fingers | Consider how the patient handles objects |

| Exudation in chronic eczema on the legs or venous ulcers | Sensitization to treatments being used |

Chronic hand dermatitis deserves special consideration. The clinical picture should first be noted and categorized and treatment prescribed. Tinea should be ruled out, whether on the basis of clinical signs or by mycology. Hand eczemas are usually multifactorial in origin, but the irritative component plays a major role. Once the patient's case has been fully studied, treatment—which should include insistence on protective measures (barriers and lotions)—should be started. Patch testing can be considered after 3 to 6 months of adequate treatment: if the eczema has not improved after this period, the possibility of a sensitivity reaction that is causing or aggravating the dermatitis (Fig. 3) should be investigated.28,29

Diagnostic Referral in Endogenous EczemaIn cases of chronic eczema initially categorized as endogenous, contact dermatitis should be investigated if the distribution is atypical. Examples would be patients with severe eyelid lesions in whom sensitization to topical medications should be assessed, or atopic patients with lesions that are more severe in the axillas than in elbow creases in whom sensitization to textile components should be ruled out. Patients diagnosed with dyshidrotic eczema who have lesions on locations other than palms or soles should also be evaluated. Acute worsening of lesions or a lack of response to appropriate treatment should suggest a possible diagnosis of sensitization to components of the topical treatments being used, thus suggesting the need for further investigation (Table 1).6,7,30

Therapeutic IndicationsA correct diagnosis will lead to therapeutic benefits for the patient; however, there are also situations in which the act of performing patch tests can facilitate clinical management itself. Although investigating sensitization without first taking an adequate medical history to guide the diagnosis of possible contact dermatitis is a poor approach to take, it might sometimes be appropriate to proceed in this way in special cases in order to involve the patient in the process. Thus, patch testing, in which the patient plays an active role, can favor adherence to therapy. Woo and coworkers11 demonstrated that quality of life improved after negative patch test results.

It is also important to order patch tests when the lesions of a chronic dermatosis worsen. This complication may be the result of secondary bacterial infection or an allergic reaction to topical medications (Fig. 4). In such cases, sensitization to corticosteroid creams may be to blame, as the anti-inflammatory effects of these creams can cause latent skin conditions to flare up.7,14,31

Referral for Legal or Social ReasonsThe results of patch tests, whether positive or negative, provide objective information about sensitization that may be important outside the strict confines of health care. They are particularly relevant in the workplace, where the presence of either irritant or allergic dermatitis can have an impact on income or employment. In such cases, according to the principle of patient benefit, adequate investigation is required even if the physician initially predicts negative results.7 Another matter entirely is the question of doing tests to foretell the likelihood of problems or to prevent them in a healthy individual (as might be proposed for future employees): given that the risk of sensitization must be avoided, patch testing in such cases would be unethical.14

Although it is rare to see the rejection of a metal component of a prosthesis because the patient is sensitized to it, the criterion of patient benefit can be used to weigh the advisability of preventive patch testing in candidates for prosthetic surgery.9

Referring a patient with contact eczema to a specialized skin allergy unit for further investigation of his or her dermatitis should be routine for Spanish dermatologists, who should apply the principle of maximum benefit by looking for clinical signs and symptoms that will provide the basis for referral.

Conflict of InterestThe author declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Borrego L. Indicaciones de derivación a una Unidad de Alergia Cutánea. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:417-422.