Biologic drugs are usually prescribed as second-line treatment for psoriasis, that is, after the patient has first been treated with a conventional psoriasis drug. There are, however, cases where, depending on the characteristics of the patient or the judgement of the physician, biologics may be chosen as first-line therapy. No studies to date have analyzed the demographics or clinical characteristics of patients in this setting or the safety profile of the agents used. The main aim of this study was to characterize these aspects of first-line biologic therapy and compare them to those observed for patients receiving biologics as second-line therapy.

Material and methodWe conducted an observational study of 181 patients treated in various centers with a systemic biologic drug as first-line treatment for moderate to severe psoriasis between January 2008 and November 2016. All the patients were registered in the Spanish Registry of Adverse Events Associated with Biologic Drugs in Dermatology.

ResultsThe characteristics of the first- and second-line groups were very similar, although the patients receiving a biologic as first-line treatment for their psoriasis were older. No differences were observed for disease severity (assessed using the PASI) or time to diagnosis. Hypertension, diabetes, and liver disease were all more common in the first-line group. There were no differences between the groups in terms of reasons for drug withdrawal or occurrence of adverse effects.

ConclusionsNo major differences were found between patients with psoriasis receiving biologic drugs as first- or second-line therapy, a finding that provides further evidence of the safety of biologic therapy in patients with psoriasis.

La utilización clínica habitual de los fármacos biológicos en el tratamiento de la psoriasis es en segunda línea, es decir, tras el uso previo de un fármaco clásico. Sin embargo, en casos particulares –particularidades del paciente o criterio médico– se realiza la indicación en primera línea. No existen estudios sobre las características demográficas, clínicas y de seguridad de los pacientes que reciben fármaco biológico en primera línea. Como objetivo primario se pretende determinar dichas características de acuerdo con la iniciación de la terapia biológica en primera o segunda línea.

Material y métodoSe realizó un estudio descriptivo, multicéntrico, de 181 pacientes que iniciaron tratamiento biológico como primer fármaco sistémico para control de su psoriasis moderada-grave, y que forman parte del Registro Español de Acontecimientos Adversos Asociados con Medicamentos Biológicos en Dermatología, entre enero de 2008 y noviembre de 2016.

ResultadosLos pacientes de ambos grupos son muy similares, si bien se evidencia que el grupo que recibe el biológico en primera línea presenta una edad más avanzada, sin que se justifique por gravedad de la enfermedad (PASI) ni por el tiempo de evolución de esta desde el diagnóstico. En este grupo de pacientes es más frecuente la presencia de hipertensión, diabetes y hepatopatía. No hemos encontrado diferencias en motivos de suspensión ni seguridad entre ambos grupos.

ConclusionesNo se han encontrado diferencias relevantes entre los 2 grupos, lo cual refuerza la seguridad de los fármacos biológicos en este contexto.

Psoriasis is a chronic disease that affects 2.3% of the Spanish population.1 Although the percentage of patients with severe forms is unknown, it is estimated to be 20.3% for psoriasis and 25.7% for psoriatic arthritis.2 Some patients are undertreated,3 and it is estimated that in Spain, only 6.8% receive systemic therapy.4

The biologic drugs approved for treatment of psoriasis are etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, ustekinumab, secukinumab, and ixekizumab. According to their summaries of product characteristics, these drugs are usually indicated as second-line agents in patients who have not responded to other treatments. However, they can be used as first-line treatment in specific clinical situations or at the physician's discretion.

The main objective of the present study, therefore, was to compare the demographic, clinical, and safety profiles of patients who received biologic treatment as a first-line option (naïve) with those of patients who received biologics as second-line therapy. We based our study on data from the Spanish Registry of Adverse Events Associated With Biologic Drugs in Dermatology (Registro Español de Acontecimientos Adversos Asociados con Medicamentos Biológicos en Dermatología [BIOBADADERM]), which, since 2008, has prospectively included patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who are receiving systemic therapy with biologic and nonbiologic drugs. Complete information on the cohort can be found on the BIOBADERM webpage (https://biobadaderm.fundacionpielsana.es/).

Material and MethodsStudy design. Study population and comparison groupsThe study population comprised patients included in the BIOBADADERM registry between January 2008 and November 2016. We divided this population into 2 cohorts: (a) a treatment-naïve cohort, ie, patients receiving a biologic as first-line therapy (etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, ustekinumab, and secukinumab—ixekizumab had not been approved when the study closed); and (b) a conventionally treated cohort, ie, patients who had previously received conventional systemic treatment (acitretin, ciclosporin, methotrexate); apremilast was not included, as it had not been approved at the time. Phototherapy was not considered systemic treatment. Patient data included sex, age, time since onset, baseline Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI), type of psoriasis, associated comorbid conditions, treatment used, reason for suspension, follow-up time, and adverse events.

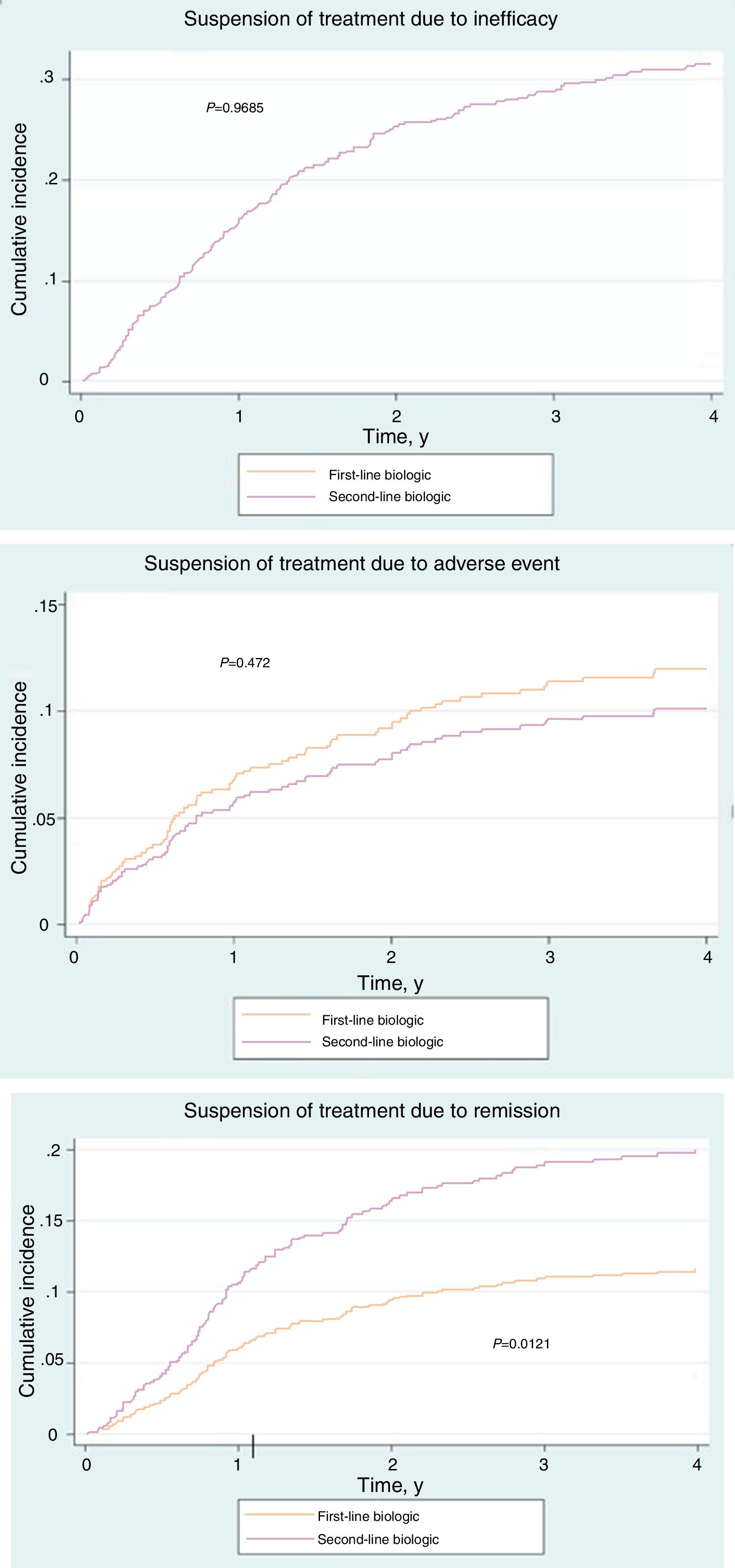

Statistical AnalysisDemographic and descriptive data are expressed as whole numbers and percentages in the case of categorical variables and as mean (SD) in the case of continuous quantitative variables. A descriptive analysis of the variables in each group was performed using the χ2 test and t test. The cumulative incidence of the reasons for suspension of therapy (inefficacy, adverse events, and remission) was presented graphically as an estimation of the probability of suspending treatment. Each of the reasons was considered to be a competitive risk for the others. The incidence rates of the adverse events (per 1000 person-years) were also estimated, with their 95% confidence interval (CI). The rates in each group were then compared using the incidence rate ratio, with its corresponding 95% CI.

ResultsThe series comprised 915 patients receiving a biologic drug: 181 patients received a biologic as their first-line treatment and 734 after their treatment with a conventional agent failed.

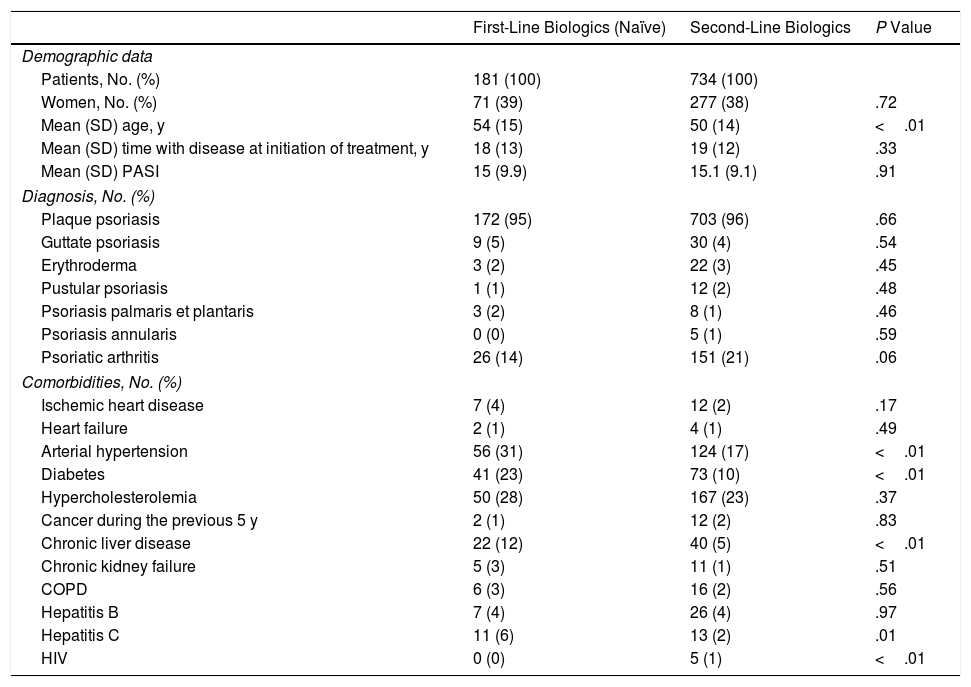

Women accounted for 39% of treatment-naïve patients. The mean (SD) PASI score was 15 (9.9), and the mean (SD) time since onset of the disease before initiation of the biologic was 18 (13) years, with no differences between the treatment-naïve group and the group treated with conventional therapy. Mean (SD) age at the initiation of biologic therapy was significantly higher in the treatment-naïve cohort (54 [15] years) than in the cohort treated with conventional therapy (P<.01).

Table 1 presents clinical data, such as type of psoriasis, and presence of psoriatic arthritis, for which no significant differences were observed, and associated comorbidities (arterial hypertension, diabetes, chronic liver disease, hepatitis C, and HIV infection), for which a statistically significantly greater presence was observed in the treatment cohort.

Patients.

| First-Line Biologics (Naïve) | Second-Line Biologics | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Patients, No. (%) | 181 (100) | 734 (100) | |

| Women, No. (%) | 71 (39) | 277 (38) | .72 |

| Mean (SD) age, y | 54 (15) | 50 (14) | <.01 |

| Mean (SD) time with disease at initiation of treatment, y | 18 (13) | 19 (12) | .33 |

| Mean (SD) PASI | 15 (9.9) | 15.1 (9.1) | .91 |

| Diagnosis, No. (%) | |||

| Plaque psoriasis | 172 (95) | 703 (96) | .66 |

| Guttate psoriasis | 9 (5) | 30 (4) | .54 |

| Erythroderma | 3 (2) | 22 (3) | .45 |

| Pustular psoriasis | 1 (1) | 12 (2) | .48 |

| Psoriasis palmaris et plantaris | 3 (2) | 8 (1) | .46 |

| Psoriasis annularis | 0 (0) | 5 (1) | .59 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 26 (14) | 151 (21) | .06 |

| Comorbidities, No. (%) | |||

| Ischemic heart disease | 7 (4) | 12 (2) | .17 |

| Heart failure | 2 (1) | 4 (1) | .49 |

| Arterial hypertension | 56 (31) | 124 (17) | <.01 |

| Diabetes | 41 (23) | 73 (10) | <.01 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 50 (28) | 167 (23) | .37 |

| Cancer during the previous 5 y | 2 (1) | 12 (2) | .83 |

| Chronic liver disease | 22 (12) | 40 (5) | <.01 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 5 (3) | 11 (1) | .51 |

| COPD | 6 (3) | 16 (2) | .56 |

| Hepatitis B | 7 (4) | 26 (4) | .97 |

| Hepatitis C | 11 (6) | 13 (2) | .01 |

| HIV | 0 (0) | 5 (1) | <.01 |

Abbreviation: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

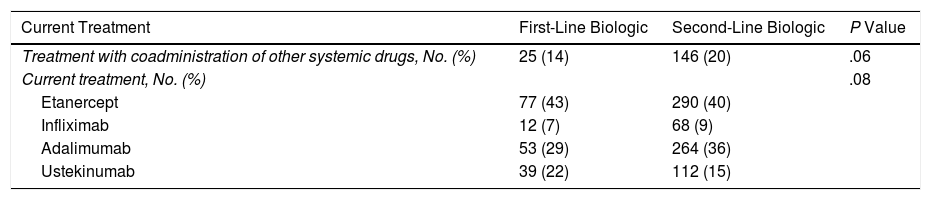

The drugs received by both groups are shown in Table 2, as is the percentage of patients who also received systemic treatment. No statistically significant differences were observed between the 2 groups for any of the drugs.

Treatment.

| Current Treatment | First-Line Biologic | Second-Line Biologic | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment with coadministration of other systemic drugs, No. (%) | 25 (14) | 146 (20) | .06 |

| Current treatment, No. (%) | .08 | ||

| Etanercept | 77 (43) | 290 (40) | |

| Infliximab | 12 (7) | 68 (9) | |

| Adalimumab | 53 (29) | 264 (36) | |

| Ustekinumab | 39 (22) | 112 (15) |

Mean follow-up time for biologics in the treatment-naïve cohort was 2.58 years, which did not differ from that of the conventionally treated cohort (2.38 years) (P=.41).

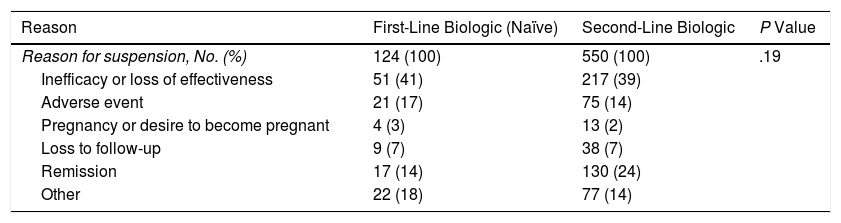

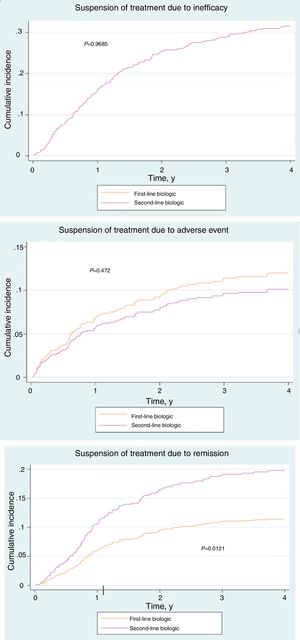

Of the 181 patients in the treatment-naïve cohort, 68.5% had stopped treatment at some time during the study. The reasons are shown in Table 3. No significant differences were found between the cohorts (P=.19). However, the cumulative incidence of withdrawal of treatment due to remission was greater in the cohort that received conventional treatment (P=.01) (Fig. 1A-C).

Reasons for Suspension of Treatment.

| Reason | First-Line Biologic (Naïve) | Second-Line Biologic | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reason for suspension, No. (%) | 124 (100) | 550 (100) | .19 |

| Inefficacy or loss of effectiveness | 51 (41) | 217 (39) | |

| Adverse event | 21 (17) | 75 (14) | |

| Pregnancy or desire to become pregnant | 4 (3) | 13 (2) | |

| Loss to follow-up | 9 (7) | 38 (7) | |

| Remission | 17 (14) | 130 (24) | |

| Other | 22 (18) | 77 (14) |

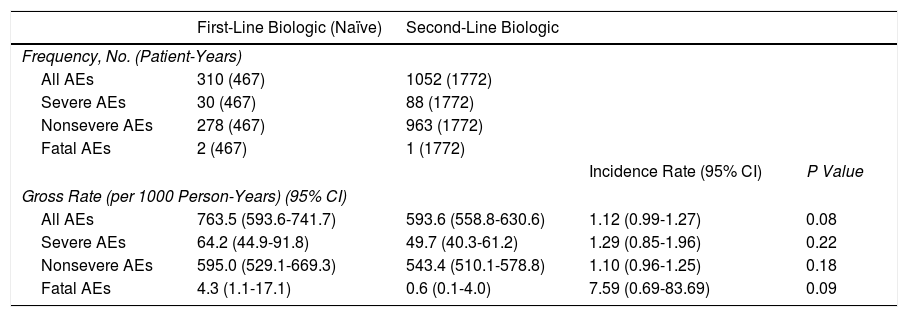

Patients in the treatment-naïve cohort presented a total of 310 adverse events (467 patient-years), of which 278 were mild, 30 severe, and 2 fatal (pancreatic adenocarcinoma and carcinoid tumor of the cecum). The overall adverse event rate (per 1000 patient-years) in the treatment-naive cohort was 763.5 (95% CI, 593.6-741.7), and there were no significant differences with respect to the patients who received conventional treatment (incidence rate ratio, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.99-1.27; P=.084) (Table 4).

Adverse Events.

| First-Line Biologic (Naïve) | Second-Line Biologic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency, No. (Patient-Years) | ||||

| All AEs | 310 (467) | 1052 (1772) | ||

| Severe AEs | 30 (467) | 88 (1772) | ||

| Nonsevere AEs | 278 (467) | 963 (1772) | ||

| Fatal AEs | 2 (467) | 1 (1772) | ||

| Incidence Rate (95% CI) | P Value | |||

| Gross Rate (per 1000 Person-Years) (95% CI) | ||||

| All AEs | 763.5 (593.6-741.7) | 593.6 (558.8-630.6) | 1.12 (0.99-1.27) | 0.08 |

| Severe AEs | 64.2 (44.9-91.8) | 49.7 (40.3-61.2) | 1.29 (0.85-1.96) | 0.22 |

| Nonsevere AEs | 595.0 (529.1-669.3) | 543.4 (510.1-578.8) | 1.10 (0.96-1.25) | 0.18 |

| Fatal AEs | 4.3 (1.1-17.1) | 0.6 (0.1-4.0) | 7.59 (0.69-83.69) | 0.09 |

Abbreviation: AE, adverse event.

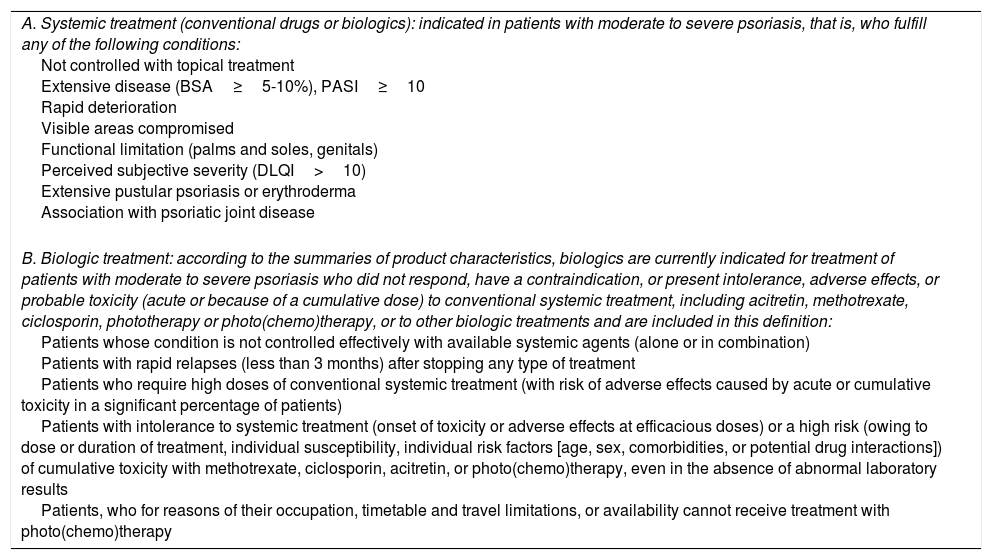

Most published data on the efficacy and safety of biologics in psoriasis refer to their use as second-line treatment in patients with moderate to severe disease. Nevertheless, the guidelines of the psoriasis group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology also include an indication for the use of these drugs in other situations (Table 5).5 Therefore, data from a biologic-naïve cohort would be of interest when investigating these aspects.

Recommendations: Eligibility Criteria for Treatment With Biologicsa

| A. Systemic treatment (conventional drugs or biologics): indicated in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis, that is, who fulfill any of the following conditions: Not controlled with topical treatment Extensive disease (BSA≥5-10%), PASI≥10 Rapid deterioration Visible areas compromised Functional limitation (palms and soles, genitals) Perceived subjective severity (DLQI>10) Extensive pustular psoriasis or erythroderma Association with psoriatic joint disease |

| B. Biologic treatment: according to the summaries of product characteristics, biologics are currently indicated for treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis who did not respond, have a contraindication, or present intolerance, adverse effects, or probable toxicity (acute or because of a cumulative dose) to conventional systemic treatment, including acitretin, methotrexate, ciclosporin, phototherapy or photo(chemo)therapy, or to other biologic treatments and are included in this definition: Patients whose condition is not controlled effectively with available systemic agents (alone or in combination) Patients with rapid relapses (less than 3 months) after stopping any type of treatment Patients who require high doses of conventional systemic treatment (with risk of adverse effects caused by acute or cumulative toxicity in a significant percentage of patients) Patients with intolerance to systemic treatment (onset of toxicity or adverse effects at efficacious doses) or a high risk (owing to dose or duration of treatment, individual susceptibility, individual risk factors [age, sex, comorbidities, or potential drug interactions]) of cumulative toxicity with methotrexate, ciclosporin, acitretin, or photo(chemo)therapy, even in the absence of abnormal laboratory results Patients, who for reasons of their occupation, timetable and travel limitations, or availability cannot receive treatment with photo(chemo)therapy |

Abbreviations: BSA, body surface area; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

The present study included 915 patients from BIOBADADERM, of whom 181 (19.78%) were treatment-naïve.

While the profile of both cohorts is very similar, naïve patients receive treatment at an older age (54 vs 50 years; P=.003). However, this finding is not explained by the degree of severity (PASI naïve 15 vs PASI conventional 15.1; P=.91) or by the time since diagnosis (naïve 18 years vs conventional 19 years; P=.33). Despite the initial caution with respect to the use of biologics in elderly persons, our group had previously confirmed the growing tendency to use these drugs in this population.6 Furthermore, it is noteworthy that in both cohorts, patients had to wait a mean of 18 years before receiving systemic treatment (biologics or systemic), although it is unknown whether these data are similar in other series.

Occasionally, the indication for a conventional drug is hampered by the presence of comorbid conditions. In fact, in this study, we observed that treatment-naïve patients more frequently had arterial hypertension (31% vs 17%; P<.01), diabetes (23% vs 10%; P<.01), chronic liver disease (12% vs 5%; P<.01), and hepatitis C (6% vs 2%; P=.015). The difference is also significant with respect to the presence of HIV infection (2% vs 1%; P<.01), although we cannot confirm that these were the direct reasons for prescription of the initial biologic.

The distribution of the biologics used is similar. Consistent with other published series,7–9 etanercept was the most frequently used drug in both groups, followed by adalimumab, ustekinumab, and infliximab. Therefore, it seems that the prescriber's criteria do not differ when choosing drugs for first- or second-line treatment.

The percentage of cases in which a systemic drug was added was comparable (14% vs 20%; P=.08). Similarly, no differences were recorded with respect to mean follow-up time (2.58 vs 2.41 years; P=.41). Therefore, the data show that patients were managed using the same clinical criteria.

The reasons for withdrawal of the drug in both cohorts were similar with respect to overall percentages (P=.19). However, in terms of cumulative incidence, suspension due to remission was significantly less frequent in the treatment-naïve cohort than in the conventional cohort (P=.01). This observation cannot be explained by differences in severity or in clinical management; therefore, if no confounders are identified, then disease control may differ depending on whether the drugs are used as first- or second-line treatment.

The overall rate (per 1000 person-years) of adverse events in the treatment-naïve cohort was slightly higher than in the cohort that received conventional treatment, although the differences were not significant (P=.08). Similarly, no differences were observed between the 2 cohorts when the rates of adverse events were analyzed separately. A total of 3 fatal adverse events were recorded (2 in the naïve cohort and 1 in the conventional cohort) (Table 4). The time when a biologic is prescribed does not seem to modify its adverse effects, and the drugs can be considered equally safe.

Undoubtedly, the use of a biologic as first-line systemic treatment raises interesting questions: Does the indication of the biologic as a first-line treatment modify the course of the disease? Does it lead to faster and more intense clearance? Can it control the potential comorbid conditions associated with the disease, especially bone and joint degeneration in patients with arthritis? Will the same safety data be recorded regardless of whether the drug is used as first-line or second-line treatment?

These questions lead us to hypothesize that early treatment of psoriasis could modify the natural course and treatment of the disease and to ask whether there would be any difference between starting with a conventional drug and starting directly with a biologic. In this respect, data on rheumatoid arthritis support the notion that use of a biologic as first-line therapy could modify inflammatory activity and severity,10–12 although we do not yet have data for psoriasis. In any case, the clinical scenario is not comparable, since rheumatoid arthritis can have a chronic degenerative course, which is typical of psoriatic arthritis, but not of psoriasis.

In clinical practice, patients often switch from one drug to another because of a lack of response or because of adverse events or comorbidities that require therapy to be modified. On the other hand, long-term use of these agents shows them to be safe,13 and, taking into account the fact that a larger percentage of biologics reach optimal therapeutic objectives than conventional drugs, we must ask why we should not start treatment with a biologic. Aside from cost and indication, we require more data on the efficacy and safety of biologics as first-line therapy in order to address this question appropriately.

One of the strengths of the present study is that it brings together data from a large cohort of patients who had not previously received biologic drugs (181) and who were continuously and homogeneously followed according to usual clinical practice at 13 different centers. The main limitation, however, is that the indication for each individual patient is not random, but is chosen based on the criteria of the prescribing physician. Consequently, the decision may be influenced by characteristics such as age, comorbid conditions, availability of drugs at a specific center, experience, and other unknown factors that could generate confounders.

The study is also limited by the fact that efficacy data are poor, since only indirect measures are available, such as the reason for suspension or the duration of treatment.

ConclusionsPatients from both groups were generally very similar, although the percentage of comorbid conditions and age at onset were higher in treatment-naïve patients. One possible explanation would be that the biologic is chosen to prevent adverse effects or interactions with comorbid conditions.

The fact that no differences were found between the groups with respect to the reasons for suspension and safety reinforces the safety of biologics in this context.

Conflicts of InterestDr. G. Carretero Hernández has acted as a consultant, speaker, and/or clinical trial investigator for AbbVie, Janssen-Cilag, Pfizer, MSD, Celgene, Novartis, Almirall S.A., and Leo-Pharma. Dr. C. Ferrándiz has acted as a consultant, speaker, and/or clinical trial investigator for AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., Pfizer, Celgene, Lilly, and Almirall S.A. and has received grant support from AbbVie. Dr. R. Rivera Díaz has acted as a consultant for AbbVie Laboratories, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., MSD, and Pfizer-Wyeth. Dr. E. Daudén Tello as acted as a consultant for AbbVie Laboratories, Amgen, Astellas, Celgene, Centocor Ortho Biotech Inc., Galderma, Glaxo, Janssen-Cilag, Leo-Pharma, MSD, Novartis, and Pfizer Inc. and has received remuneration from Abbott Laboratories, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen-Cilag Pty Ltd., Leo-Pharma, MSD, Novartis, and Pfizer Inc. He has also acted as a speaker for AbbVie Laboratories, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., MSD, and Pfizer Inc. and has received grant support from AbbVie Laboratories, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Pfizer Inc. Dr. P. de la Cueva-Dobao has acted as a consultant for Janssen-Cilag, AbbVie, MSD, Pfizer, and Leo-Pharma. Dr. E. Herrera-Ceballos has acted as a consultant and speaker for AbbVie Laboratories, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Pfizer-Wyeth. Dr. I. Belinchón Romero has acted as a consultant for Pfizer-Wyeth, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., MSD, Almirall S.A., Lilly, and Leo-Pharma and as a speaker for AbbVie, Pfizer-Wyeth, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., Novartis, and MSD. Dr. J.L. López-Estebaranz has acted as a consultant for Abbott Laboratories, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., MSD, and Pfizer-Wyeth and as a speaker for AbbVie Laboratories, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., MSD, and Pfizer-Wyeth. Dr. M. Alsina Gibert has acted as a consultant for AbbVie Laboratories and Merck/Schering-Plough. Dr. J.L. Sánchez-Carazo has acted as a consultant for AbbVie Laboratories, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., MSD, and Pfizer-Wyeth. Dr. M. Ferrán Farrés has acted as a consultant for MSD, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Janssen and as a speaker for MSD, AbbVie, and Janssen. She has also worked as a researcher for MSD, AbbVie, Pfizer, and Janssen. Dr. J.M. Carrascosa Carrillo has acted as a consultant and speaker for AbbVie Laboratories, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc., MSD, Pfizer-Wyeth, Novartis, and Celgene. Dr. M. Llamas Velasco has received financial support for participating in conferences from AbbVie, Janssen, and Novartis and has acted as a speaker for AbbVie and Novartis. Dr. D. Ruiz Genao has received financial support for participating in conferences from Pfizer, AbbVie, Janssen, and Novartis and has acted as a speaker for AbbVie, Pfizer, Janssen, and Novartis. Dr. I. García-Doval has received financial support for participating in conferences from Merck/Schering-Plough, Pfizer, and Janssen. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Hernández GC, Ferrándiz C, Díaz RR, Tello ED, de la Cueva-Dobao P, Gómez-García FJ, et al. Descripción de los pacientes que reciben biológicos como primer tratamiento sistémico en el registro BIOBADADERM durante el periodo 2008-2016. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:617–623.