Oral tetracyclines and topical antibiotics have been used to treat papulopustular rosacea (PPR) for years, but it is not uncommon to find patients who do not respond to this standard treatment. In such refractory cases, oral azithromycin has proven to be an effective option.

Material and methodWe conducted a prospective pilot study of 16 patients with PPR who were treated with oral azithromycin after a lack of response to oral doxycycline and metronidazole gel. At the first visit, the patients were assessed for baseline severity of PPR on a 4-point clinical scale and started on oral azithromycin. At the second visit, response to treatment in terms of improvement from baseline was evaluated on a 3-point scale. Patients were then scheduled for follow-up visits every 12 weeks to assess long-term effectiveness.

ResultsAll 16 patients experienced an improvement in their PPR following treatment with oral azithromycin. Eight weeks after completion of treatment, 14 patients (87.5%) showed complete or almost complete recovery (slight or no residual redness and complete clearance of papules and pustules). Only 2 patients experienced a new episode of inflammatory PPR lesions during follow-up.

ConclusionsThe findings of this pilot study suggest that oral azithromycin could be a very effective short-term and long-term treatment for RPP resistant to conventional treatment.

El tratamiento de la rosácea papulopustulosa (RPP) ha consistido durante años en el uso de tetraciclinas orales y antibióticos tópicos. Pero no es infrecuente encontrar casos de RPP resistentes al tratamiento convencional. Azitromicina oral ha demostrado ser una opción eficaz para estos pacientes no respondedores.

Material y métodoSe realizó un estudio piloto prospectivo con 16 pacientes con RPP no respondedores al tratamiento convencional (doxiciclina oral y metronidazol gel) que recibieron tratamiento con azitromicina oral. En la visita inicial (visita 1) se realizó una valoración basal del estadio clínico de la RPP, según 4 niveles de gravedad progresiva, y se inició tratamiento con azitromicina oral. A las 8 semanas de finalizar el tratamiento (visita 2) se evaluó la respuesta clínica según 3 niveles de mejoría respecto al estadio clínico basal. Posteriormente, para evaluar la eficacia de azitromicina oral a largo plazo, se realizaron visitas periódicas cada 12 semanas.

ResultadosTodos los pacientes que recibieron tratamiento con azitromicina oral mejoraron de su RPP. A las 8 semanas de finalizar el tratamiento se objetivó un eritema facial residual débil o nulo, con desaparición completa de las pápulas y/o pústulas en el 87,5% de los pacientes. En cuanto al mantenimiento de la eficacia a largo plazo, únicamente 2 pacientes presentaron una recidiva de lesiones inflamatorias de RPP.

ConclusionesLos resultados de nuestro estudio evidencian que azitromicina oral podría ser un fármaco de gran eficacia a corto y largo plazo para el manejo de aquellos casos de RPP resistentes al tratamiento convencional.

Papulopustular rosacea (PPR) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by facial erythema with papules and/or pustules located preferentially on the face.

Traditionally, it has been treated with oral tetracyclines (mainly doxycycline) and topical antibiotics, such as metronidazole.1 An increasing number of treatments have become available in recent years, including oral isotretinoin2 and anti-parasite drugs such as ivermectin, which can be administered topically3 or orally.4 In clinical practice, however, there are an appreciable number of challenging cases that do not respond to these conventional treatments. Azithromycin, a macrolide antibiotic, has been shown to a safe, effective treatment for PPR.5 We designed a study to evaluate the use of azithromycin to treat PPR that failed to respond to conventional treatment at our hospital.6

Material and MethodsDesignWe conducted a prospective pilot study of 16 patients with PPR between March 2016 and September 2017.

Inclusion and Exclusion CriteriaWe included patients with PPR who had received conventional treatment with doxycycline 100 mg tablets every 24hours and metronidazole 0.75% topical gel every 24hours for 84 days and who had 1) experienced clinical deterioration (an increase in the number of inflammatory lesions) as a result of this treatment or 2) experienced early recurrence (return of lesions within 8 weeks of treatment completion) despite a reduction in lesion number during treatment.

Patients with a known history of heart disease were excluded.

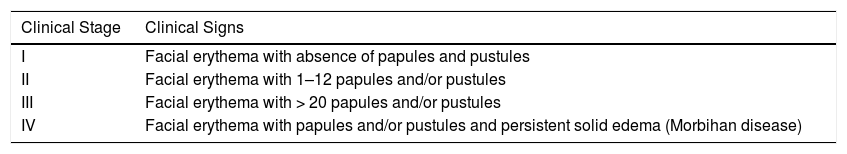

All the patients were informed in detail about oral azithromycin and alternative treatments and about the conditions of the study. Written consent was obtained in all cases. PPR was graded according to 4 levels of progressive clinical severity7 (Table 1).

Clinical Stages of Papulopustular Rosaceaa

| Clinical Stage | Clinical Signs |

|---|---|

| I | Facial erythema with absence of papules and pustules |

| II | Facial erythema with 1–12 papules and/or pustules |

| III | Facial erythema with > 20 papules and/or pustules |

| IV | Facial erythema with papules and/or pustules and persistent solid edema (Morbihan disease) |

The patients were administered azithromycin 500mg tablets for 12 weeks following the treatment regimen proposed by Bakar et al.8: 500mg/d for 3 consecutive days a week for a month, followed by 250mg/d (half a 500-mg tablet) for 3 consecutive days a week for another month, followed by 500mg once a week for another month (total treatment duration: 12 weeks).

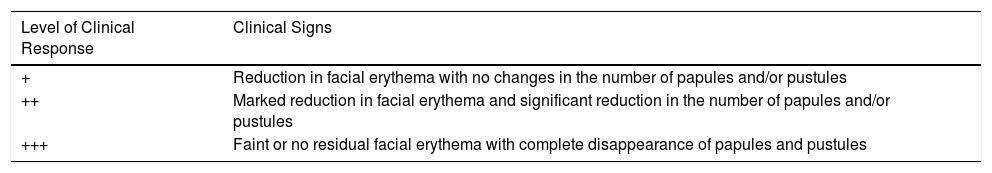

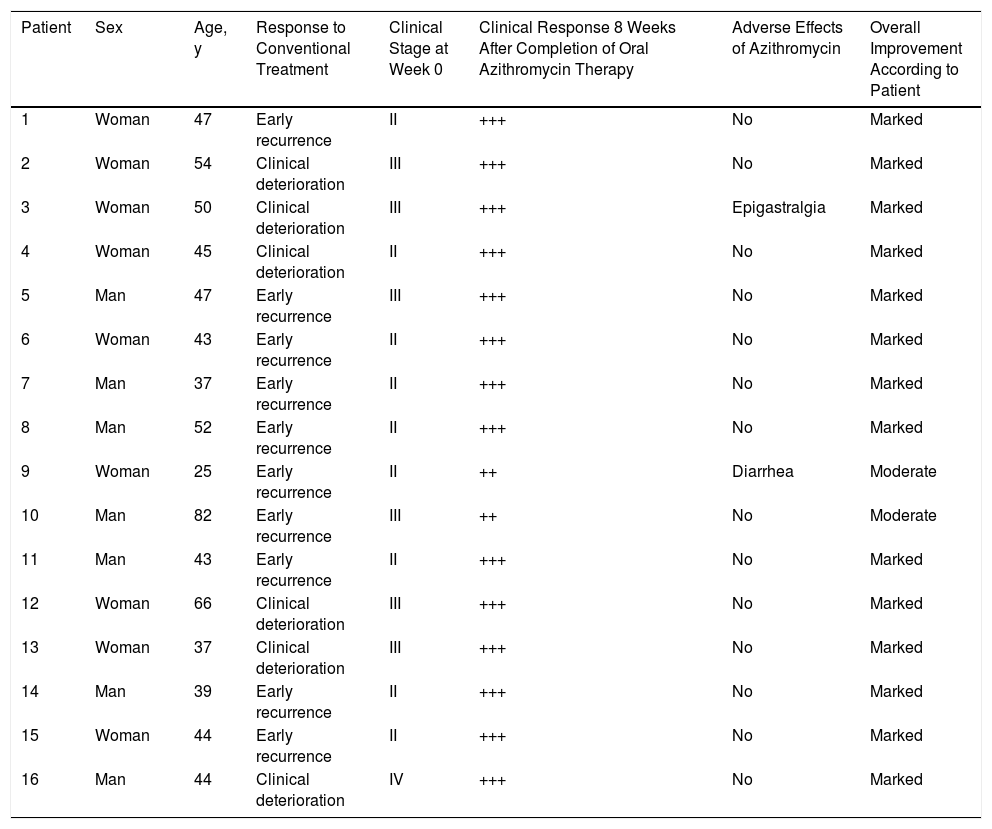

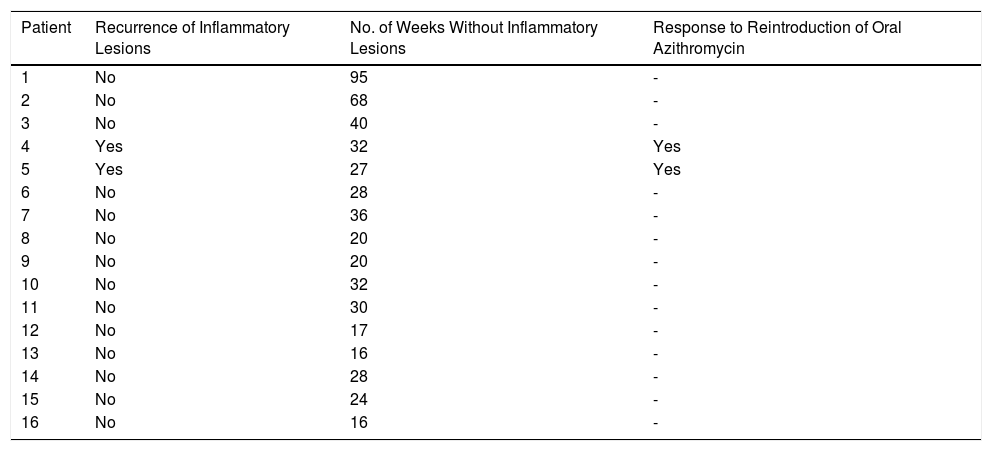

Follow-upPatients were scheduled for 2 main visits to check the short-term effectiveness of oral azithromycin and a series of subsequent visits to check long-term effectiveness. At the baseline visit (visit 1), once the patients had given their informed consent to participate in the study, the severity of their PPR was evaluated and they were started on the established 12-week course of oral azithromycin. The second visit took place 8 weeks after the end of treatment. At this visit, clinical response was graded on a 3-point scale7 according to improvement from baseline (Table 2). A record was also made of adverse effects and of how the patients rated their improvement (mild, moderate, or marked). Table 3 summarizes the patients’ demographics and response to conventional treatment and oral azithromycin. The subsequent visits to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of azithromycin were held every 12 weeks. The results of the evaluation (recurrence of inflammatory lesions, number of weeks without inflammatory lesions, and response to reintroduction with oral azithromycin in patients who experienced recurrence) are summarized in Table 4.

Levels of Clinical Response to Treatment With Oral Azithromycin in Patients With Papulopustular Rosaceaa

| Level of Clinical Response | Clinical Signs |

|---|---|

| + | Reduction in facial erythema with no changes in the number of papules and/or pustules |

| ++ | Marked reduction in facial erythema and significant reduction in the number of papules and/or pustules |

| +++ | Faint or no residual facial erythema with complete disappearance of papules and pustules |

Demographic Characteristics, Response to Conventional Treatment, and Changes in Clinical Staging in Patients With Papulopustular Rosacea Treated With Oral Azithromycin.

| Patient | Sex | Age, y | Response to Conventional Treatment | Clinical Stage at Week 0 | Clinical Response 8 Weeks After Completion of Oral Azithromycin Therapy | Adverse Effects of Azithromycin | Overall Improvement According to Patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Woman | 47 | Early recurrence | II | +++ | No | Marked |

| 2 | Woman | 54 | Clinical deterioration | III | +++ | No | Marked |

| 3 | Woman | 50 | Clinical deterioration | III | +++ | Epigastralgia | Marked |

| 4 | Woman | 45 | Clinical deterioration | II | +++ | No | Marked |

| 5 | Man | 47 | Early recurrence | III | +++ | No | Marked |

| 6 | Woman | 43 | Early recurrence | II | +++ | No | Marked |

| 7 | Man | 37 | Early recurrence | II | +++ | No | Marked |

| 8 | Man | 52 | Early recurrence | II | +++ | No | Marked |

| 9 | Woman | 25 | Early recurrence | II | ++ | Diarrhea | Moderate |

| 10 | Man | 82 | Early recurrence | III | ++ | No | Moderate |

| 11 | Man | 43 | Early recurrence | II | +++ | No | Marked |

| 12 | Woman | 66 | Clinical deterioration | III | +++ | No | Marked |

| 13 | Woman | 37 | Clinical deterioration | III | +++ | No | Marked |

| 14 | Man | 39 | Early recurrence | II | +++ | No | Marked |

| 15 | Woman | 44 | Early recurrence | II | +++ | No | Marked |

| 16 | Man | 44 | Clinical deterioration | IV | +++ | No | Marked |

Long-term Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Papulopustular Rosacea Following Treatment With Oral Azithromycin.

| Patient | Recurrence of Inflammatory Lesions | No. of Weeks Without Inflammatory Lesions | Response to Reintroduction of Oral Azithromycin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | No | 95 | - |

| 2 | No | 68 | - |

| 3 | No | 40 | - |

| 4 | Yes | 32 | Yes |

| 5 | Yes | 27 | Yes |

| 6 | No | 28 | - |

| 7 | No | 36 | - |

| 8 | No | 20 | - |

| 9 | No | 20 | - |

| 10 | No | 32 | - |

| 11 | No | 30 | - |

| 12 | No | 17 | - |

| 13 | No | 16 | - |

| 14 | No | 28 | - |

| 15 | No | 24 | - |

| 16 | No | 16 | - |

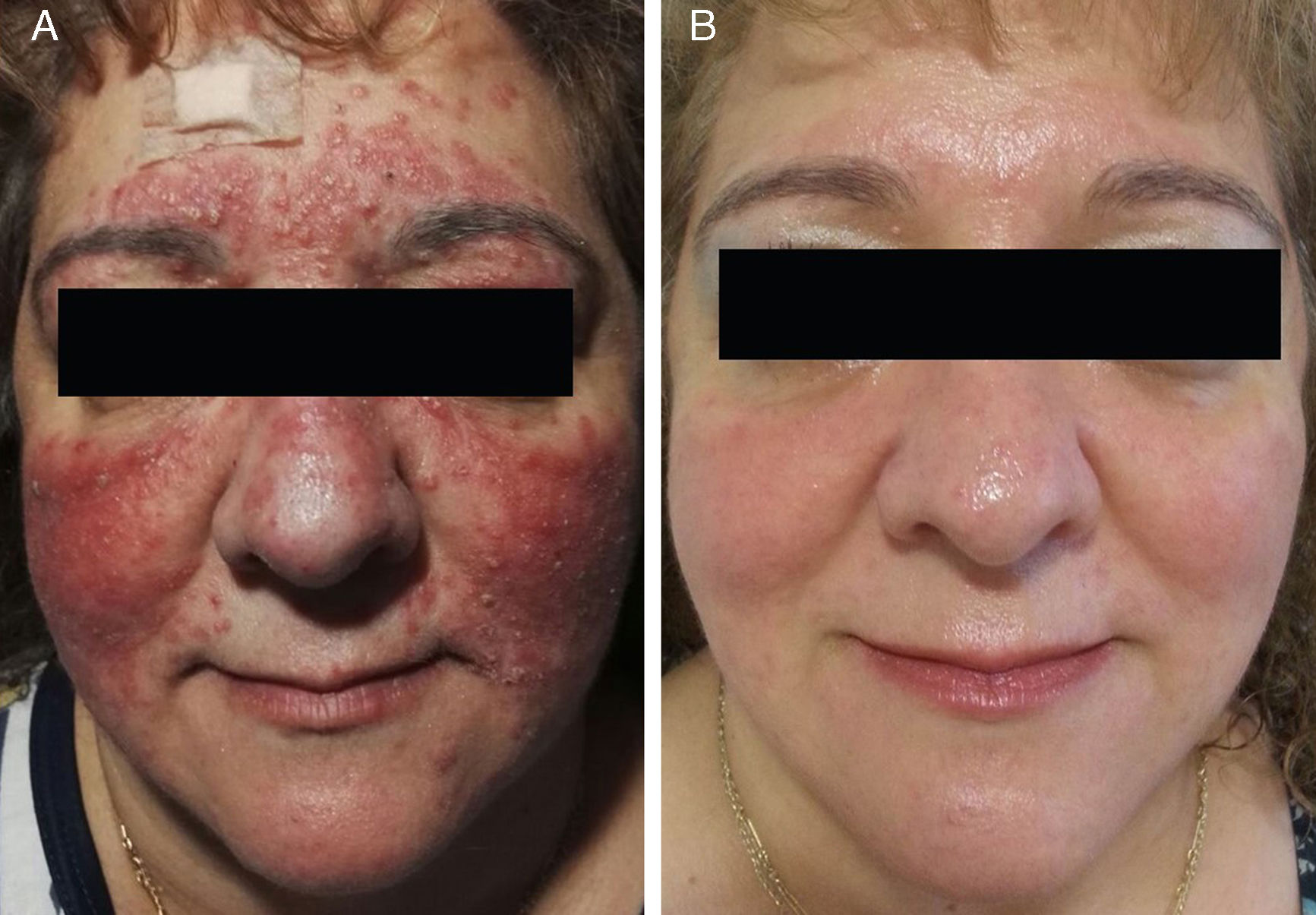

Sixteen patients (9 women and 7 men) with a mean age of 47 years (range, 25-82 years) were included. Conventional PPR treatment had resulted in clinical deterioration in 6 cases (Fig. 1A and Fig. 2A). The remaining 10 patients had shown an initial improvement but the lesions returned within 8 weeks of stopping treatment.

The individual levels of clinical response at 8 weeks are shown in Table 3. All 16 patients improved following treatment with oral azithromycin. At the baseline visit, 9 patients had stage II disease, 6 patients had stage III disease (Fig. 1A and 2A), and 1 patient had stage IV disease. At the second visit, 8 weeks after the end of treatment, 14 patients (87.5%) showed faint or no residual erythema and complete clearance of papules and/or pustules (+++) (Fig. 1B and 2B). The other 2 patients showed a marked reduction in facial erythema and a significant reduction in the number of papules and/or pustules (++).

None of the patients described their improvement as mild. Fourteen patients (87.5%) considered that that they had undergone a marked improvement, while 2 (12.5%) considered that they had undergone a moderate improvement.

No new inflammatory lesions (papules or pustules) were observed at the follow-up visit 8 weeks after treatment completion in 14 patients (87.5%). The reintroduction of oral azithromycin in the 2 patients who did experience recurrence resolved the lesions in both cases (Table 4).

Two patients (12.5%) reported adverse gastrointestinal effects but these did not lead to treatment discontinuation.

DiscussionAzithromycin is a macrolide antibiotic that has been in use since the 1980s. It is a widely used antibiotic that is typically used to treat a range of infections, including bronchitis, pneumonia, otitis, and sexually transmitted infections.

Demodex folliculorum,9Chlamydia pneumoniae,10Helicobacter pylori,11 and intestinal bacteria overgrowth have all been implicated in the etiology and pathogenesis of rosacea.12 Environmental stress can also give rise to the overproduction of reactive oxygen species, activating the inflammatory cascade.13,14 Azithromycin appears to have anti-inflammatory in addition to antibiotic properties,15 as it blocks the formation of reactive oxygen species, explaining its usefulness in the treatment of PPR.16,17

Although the recommendation to use azithromycin in the treatment of PPR is based on level B evidence, compared with level A for doxycycline,1,18 azithromycin has proven to be as effective as doxycycline in this setting,5 and as such may be a useful option for patients who experience adverse effects or who do not respond to conventional treatment.19 It is also important to note that there are a substantial number of patients who experience clinical deterioration during conventional treatment,6 possibly due to acquired tetracycline resistance.20 All the patients in our study had received conventional treatment before being treated with azithromycin; 37.5% had experienced a worsening of their PPR during treatment while the remaining 62.5% had experienced early recurrence (appearance of new inflammatory lesions in the 8 weeks after stopping treatment). Azithromycin has been found to be a very effective treatment for PPR in isolated case studies6,21,22 and series.7,8,23,24 In our series, 8 weeks after finishing azithromycin, 87.5% of patients had only faint or no facial erythema and their papules and pustules had completely disappeared. The remaining 12.5% experienced a marked reduction in facial redness and a significant reduction in the number of papules and/or pustules. Our series included a 44-year-old man who had had persistent solid facial edema (Morbihan disease) for 10 years that had been treated with oral doxycycline,25 oral isotretinoin,26 and oral ivermectin.4 The rest of his history was unremarkable. His manifestations had worsened with all 3 treatments, but the use of oral azithromycin led to the complete disappearance of the eyebrow swelling and inflammatory lesions. Just 2 patients (12.5%) experienced recurrence of the inflammatory lesions (papules and/or pustules) in the long-term follow-up and they both responded to the reintroduction of oral azithromycin.

It is important to recall that tetracyclines are contraindicated in pregnant women. Azithromycin is a category B pregnancy drug according to the US Food and Drug Administration and it has achieved satisfactory clinical results, without adverse effects, in pregnant women with PPR.27

Azithromycin offers pharmacokinetic advantages over conventional treatments for the treatment of rosacea, including rapid uptake by cells and sustained tissue concentrations.28 These advantages reduce the frequency of administration and as such increase the chances of treatment adherence.6 Azithromycin also has a lower rate of adverse effects than tetracyclines,29 although low-dose doxycycline (40mg/24h) has a similar effectiveness to standard-dose doxycycline (100mg/24h), in addition to fewer adverse effects.18 It is important to be familiar with the proarrhythmogenic potential of azithromycin, as the drug has been linked to QT-interval prolongation. In 1 study, the use of azithromycin to treat infections other than PPR for 5 consecutive days in patients with a high baseline cardiovascular risk was associated with a small increase in cardiovascular deaths.30 Compared with amoxicillin, azithromycin therapy over 5 days was estimated to cause 47 additional cardiovascular deaths for each million courses of treatment; the corresponding figure for patients with a high risk of cardiovascular disease was 245.30 A recent meta-analysis of observational studies did not find antibiotic therapy with azithromycin over 5 days to be associated with an increased risk of death in the younger population (hazard ratio [HR], 0.95; 95% CI, 0.66-1.09), although an increased risk was observed in the older population (HR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.23-2.19).31 It would therefore seem advisable to use treatments other than azithromycin in elderly patients with PPR or in patients with known heart disease, as they may be more susceptible to the drug's arrhythmogenic effects. None of the patients in our study had known heart disease (Table 3). Two were aged over 65 years and neither of them developed adverse cardiovascular effects. The only adverse effects reported in the group were gastrointestinal complaints (epigastralgia and diarrhea in 2 patients [12.5%]). In both cases, the effects were mild, resolved spontaneously, and did not lead to treatment discontinuation.

There are a number of very interesting studies analyzing the possible link between long-term macrolide treatment and bacterial resistance in the field of pulmonology, where azithromycin, thanks to its anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antibacterial properties, has been associated with reduced exacerbation frequency, reduced sputum volume, and improved lung function.32 Although we used the treatment regimen proposed by Bakar et al.8 (500mg/d 3 days a week for a month followed by 250mg/d 3 days a week for a month, and finally 500mg/d once a week for a month (total of 3 months), longer regimens have been described for azithromycin in patients with bronchiectasis (250 or 500mg/d 3 or 7 times a week for 6–12 months).32 Macrolide-resistant commensal bacteria that can be transmitted within the community (e.g., oropharyngeal streptococci) have been detected in patients with bronchiectasis. Patients treated with azithromycin for 5 to 12 months have been found to have a higher proportion of macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, although there does not appear to be a risk of domestic transmission in such cases. Finally, there have been reports of azithromycin resistance in isolated S pneumoniae strains after 6 months of treatment. More studies are needed to understand the as yet unclear clinical significance of increased bacterial resistance in long-term therapy with azithromycin.32

Our study has some limitations, including the fact that we did not calculate a sample size in advance, use a comparative group, or perform microbiologic or histologic studies of the inflammatory lesions.

ConclusionsAlthough more randomized controlled trials are needed to compare oral azithromycin and doxycycline, azithromycin has been shown to be an effective short-term and long-term treatment for PPR. In addition, it has a good safety profile and can therefore be considered an alternative for treating refractory PPR.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Lova Navarro M, Sánchez-Pedreño Guillen P, Victoria Martínez AM, Martínez Menchón T, Corbalán Vélez R, Frías Iniesta J. Rosácea papulopustulosa: respuesta al tratamiento con azitromicina oral. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:529–535.