Psoriasis is a chronic, systemic inflammatory disorder with multiple comorbidities.

The most common comorbidities are mental disorders, especially depression, which can interact negatively with psoriasis to produce a dangerous vicious circle. Depression in psoriasis has traditionally been explained as a response to psychosocial factors and impaired quality of life.

However, a new hypothesis linking depression and psoriasis through chronic inflammation offers insights that should help us to understand and treat these diseases. In this approach, new drugs and lifestyle have an important role.

La psoriasis es un proceso inflamatorio crónico y sistémico con múltiples comorbilidades. Entre las más frecuentes se encuentran las enfermedades mentales y en especial la depresión, con la que interrelacionan negativamente llegando a producir un peligroso círculo vicioso. Clásicamente se ha explicado la depresión de los pacientes con psoriasis como reactiva a factores psicosociales y el deterioro en la calidad de vida. Sin embargo, la asociación de estas dos patologías a través del proceso inflamatorio crónico ofrece una nueva hipótesis para su comprensión y tratamiento. Este enfoque incide en nuevos fármacos y la importancia del estilo de vida.

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects between 2% and 3% of the population. The physical and psychosocial impact of the disease is considerable and negatively affects the patient's quality of life.1 While psoriasis has traditionally been considered to be a disease of the skin, there is now ample evidence of its systemic nature and concomitant involvement of other organs and systems. The prevalence of comorbidities is high. These include psoriatic arthritis, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver, inflammatory bowel disease, smoking, alcohol abuse, as well as psychiatric disorders, in particular anxiety and depression. When suspected, these conditions should be diagnosed promptly and treated because in combination they can produce a complex negative interrelation.2 The role of the dermatologist is, therefore, critical in the comprehensive and interdisciplinary management of psoriasis.3,4

Association Between Psoriasis and DepressionPsoriasis is associated with various affective disorders, in particular anxiety and depression.5 Anxiety has been observed in 43% of patients with this disease.6

The prevalence of comorbid depression in patients with psoriasis is estimated at between 20% and 30%, and rates as high as 62% have been reported.7,8 These rates are higher1,5 than those observed in the general population and in patients with other skin diseases.9 The prevalence of depression in cases of more severe psoriasis is even higher.8,10,11 Kurd et al. confirmed these findings in a large case series of patients with psoriasis: they found a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation (39%, 31%, and 44%, respectively), which increased in the most severe cases.12

Moreover, depression in patients with psoriasis tends to be more severe than in the general population and more often associated with anxiety and suicidal ideation (between 2.5% and 9.7%, respectively).13

Factors Contributing to Depression in Patients with PsoriasisThe connection between the skin and the mind is complex. The skin and the nervous system share a common embryonic origin. The skin is the body's envelope, the outer layer that establishes our identity. It contains us and protects us. It plays an essential role in our interaction with the environment that surrounds us. Through the skin we perceive the world and are perceived by it. It helps us to communicate with others and to express our feelings and emotions.

Although the association between psychiatric and dermatological disorders is well known, not all the links between them have been identified.

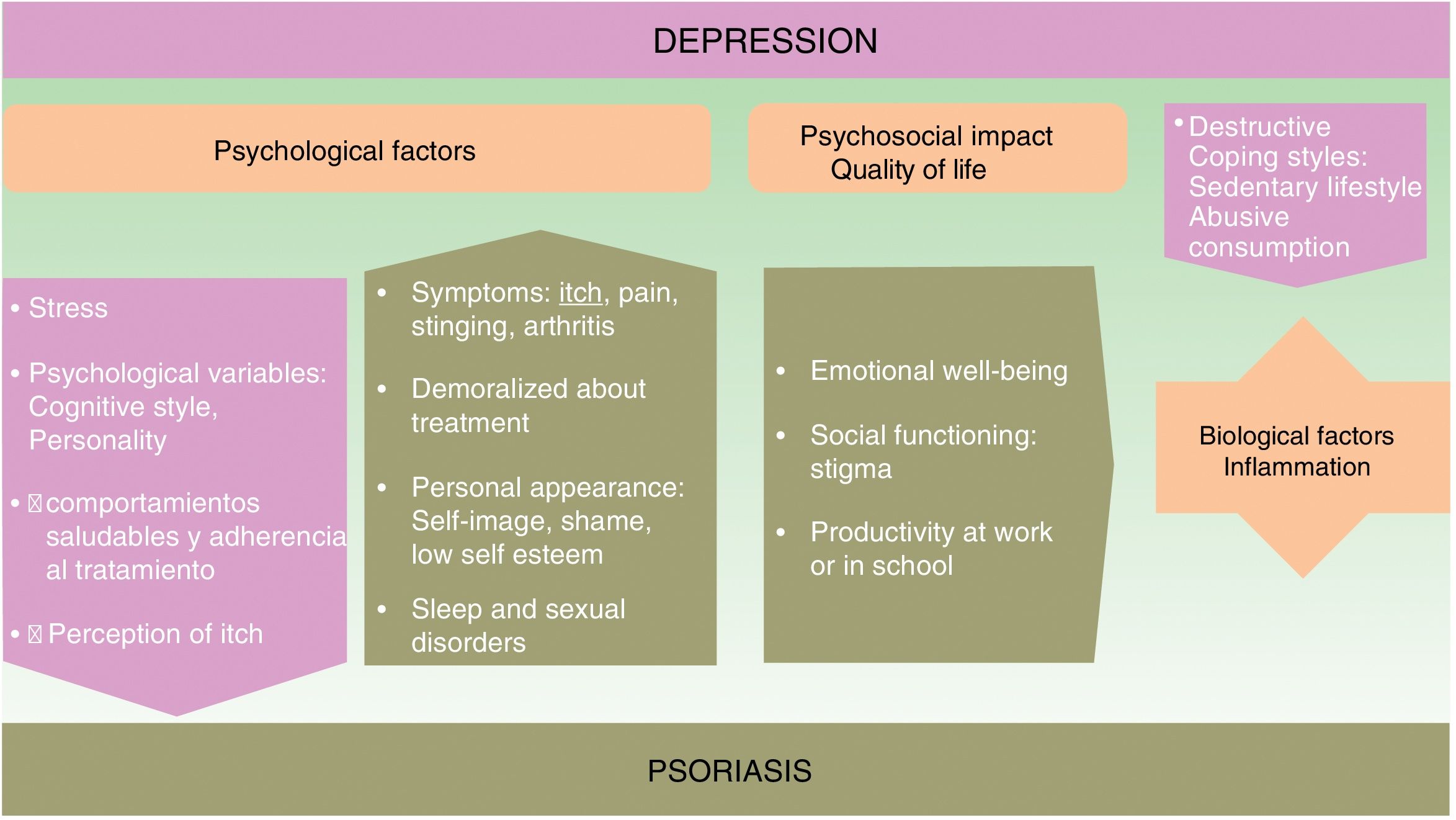

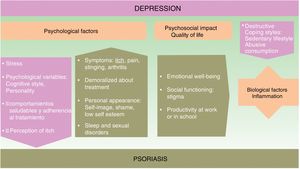

The onset and course of depression in patients with psoriasis appears to be influenced by multiple factors (see Fig. 1).

Psychological FactorsUsing a biopsychosocial model to assess psoriasis can help us to identify many of the factors involved and facilitate a multidisciplinary approach to the management of the disease, which can improve the prognosis.

The symptoms of psoriasis, including painful skin lesions that itch, sting, and bleed, may affect more than just the patient's skin. The condition also has a negative effect on the patient's well-being, giving rise to anxiety concerning personal appearance, emotional distress, feelings of shame, low self-esteem, stigmatization, social exclusion, and employment-related problems; in short, it often has considerable psychological repercussions and is associated with anxiety and depression.14–16 The patient's response to treatment can be influenced by its duration, their satisfaction or dissatisfaction, and by personality traits and cognitive style.

A depressed state in a psoriatic patient can have a negative impact on their coping strategies and self-care, and consequently on disease prognosis. Depressed patients tend to develop more destructive coping strategies and unhealthy habits.17,18 These include a sedentary lifestyle, smoking, failure to adopt a healthy diet (such as the Mediterranean diet), as well as the harmful consumption of alcohol, which they sometimes use to self-medicate.19 In such cases, adherence to treatment deteriorates20 and certain therapies, such as photochemotherapy, are less effective.21

Quality of LifeIn about 80% of cases, patients with psoriasis experience a significant decrease in emotional well-being, social functioning capacity, and productivity in work or at school.22

The use of quality-of-life scales in clinical protocols helps us to make informed decisions about the best treatment plan to use in this complex disease. These instruments help us to assess important aspects, such as disability and socioeconomic burden. Four of the most commonly used scales are the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), SKINDEX-29 (a scale that can predict mental health problems), the PSO-LIFE questionnaire, and the Psoriasis Disability Index (PDI). Cumulative life course impairment (CLCI) is a construct that allows us to assess cumulative disability and the degree of interference with the patient's full life potential.23

We must also bear in mind that the patient's score can be negatively affected or confounded by depressive symptoms because these scales include items that relate to coping as well as interference with work and social activities.

Biological FactorsAnother reason why etiological and pathogenic factors should be considered in this setting is that the prevalence of depression is higher in psoriasis than in other disfiguring dermatological diseases.

ComorbidityThe presence of comorbid disease increases the negative interrelation in both psoriasis and depression.24

Epidemiological studies on major depression show a high incidence of inflammatory disorders, such as dermatological, autoimmune, and cardiovascular diseases, as well as diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, asthma and allergies.25,26 Immune and inflammatory dysregulation appear to be among the etiological factors involved.

InflammationAlthough it is unclear whether depression is a primary inflammatory disease, a growing body of evidence indicates that inflammation plays a role in the pathophysiology of mental illness, including major depression.

The negative bidirectional relationship linking depression and inflammation has been demonstrated. Depression, early adverse experiences, and difficulties in relating to others all favor stress responses and increase inflammation, which, in turn, can exacerbate the depression.27 In response to stress, the sympathetic nervous system promotes the release of amines (norepinephrine and others), thereby stimulating the proliferation of myeloid cells (monocytes, for example). These cells interact with other stress-induced substances, some of which, such as lipopolysaccharides and flagellin, are derived from bacteria (the intestinal microbiome, for example), but more often stress-induced damage-associated molecular patterns. In addition, corticosteroid resistance is produced by the inhibitory effect on the receptors that activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, further increasing the inflammatory response.28

In a similar way to what occurs in the microenvironment of the skin, in the nervous system the inflammatory response is maintained by the interaction between cytokine-receptor and cytokine-producing elements, such as astrocytes, microglia and oligodendrocytes.29

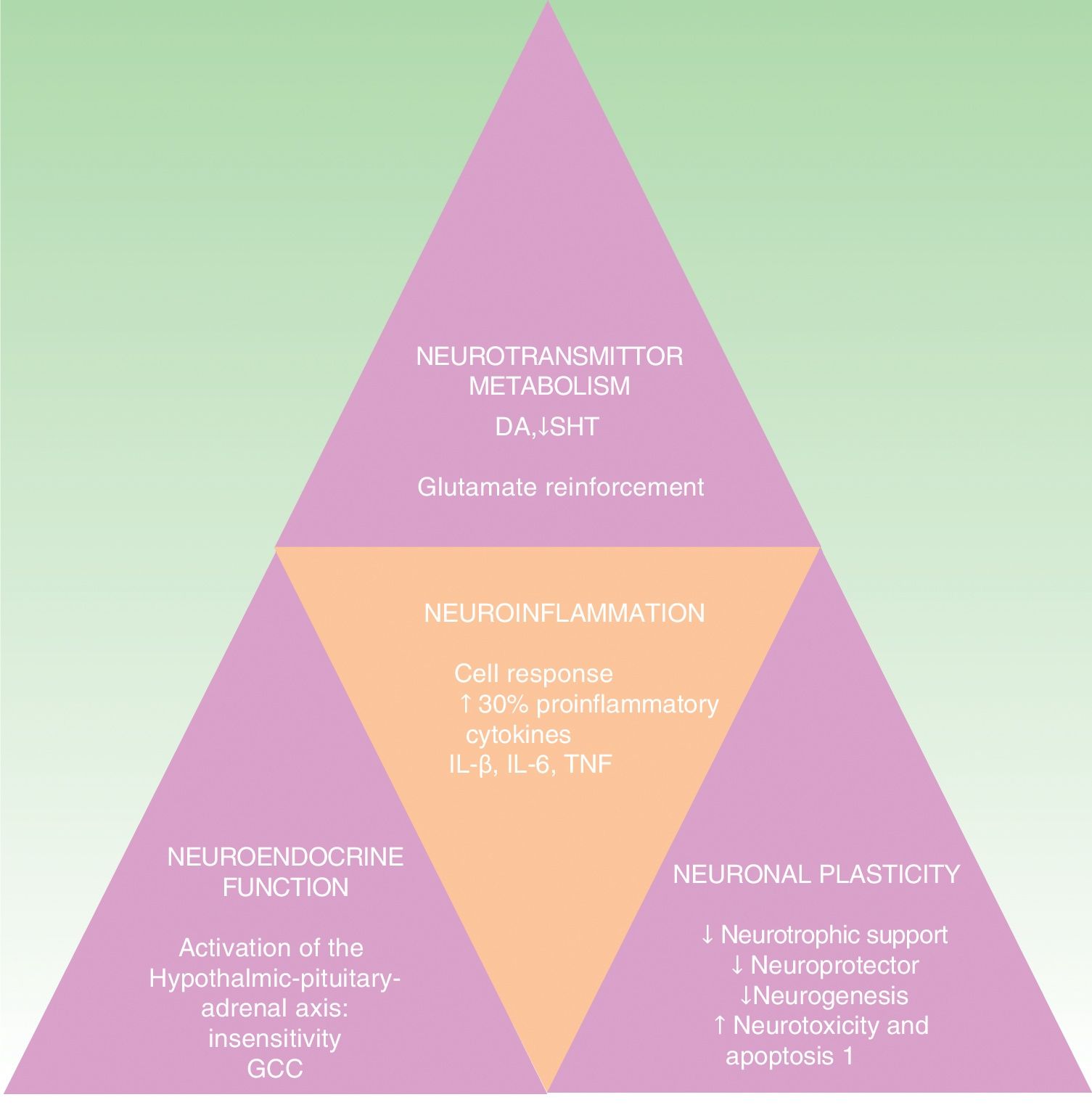

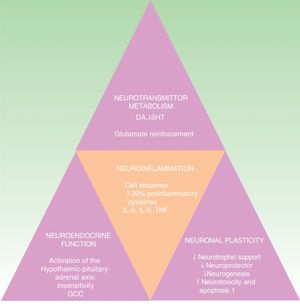

The cytokine hypothesis explains the connection between the immune system and the neuroendocrinal and behavioral alterations that occur in certain forms of depression. It is supported by numerous studies that demonstrate a 30% elevation of proinflammatory cytokines in patients with depression compared to the healthy population. These cytokines include interleukin (IL) 1ß, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), C-reactive protein (CRP), adhesion molecules, and prostaglandins.19,30,31 These inflammatory biomarkers cross the blood brain barrier and interact with virtually all the known pathophysiological spheres involved in depression. They affect the metabolism of neurotransmitters (such as dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate), neuroendocrine function, and even neuroplasticity through the confluence of decreased neurotrophic support, neuroprotective function and neurogenesis in conjunction with an increase in neurotoxicity and neuronal apoptosis.32–34 This hypothesis is in line with the neuropathological findings that characterize depressive disorders, including the reduction of hippocampal volume (Fig. 2).35 It would explain the high incidence of major depression in patients with inflammatory diseases and patients receiving immunotherapy with interferon α (IFN-α), IL-2 and IL-12 for infectious diseases (such as hepatitis C) and cancer.36 It is also supported by the fact that the administration of inflammatory cytokines produces a symptomatic picture called sick behavior, a condition that includes many symptoms that fall within the scope of depressive disorder.37–40

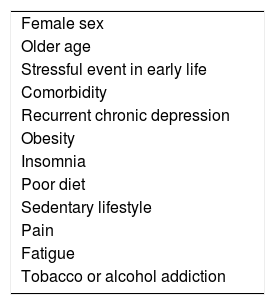

All these facts support the concept of depression as a heterogeneous disease in which inflammation can, at least in some cases, play an important role. A novel change in our approach to this disease would be to identify a subgroup of patients who respond to anti-inflammatory treatment by detecting possible biomarkers or endophenotypes (Table 1).41 Such a group might include the 30% of patients with depression who are resistant to current treatments.42

Factors Associated with Increased Risk of Inflammation That Could Indirectly Facilitate the Detection of the Inflammatory Phenotype.

| Female sex |

| Older age |

| Stressful event in early life |

| Comorbidity |

| Recurrent chronic depression |

| Obesity |

| Insomnia |

| Poor diet |

| Sedentary lifestyle |

| Pain |

| Fatigue |

| Tobacco or alcohol addiction |

Source: Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 201541

The endophenotypes correspond to the biochemical, neurophysiological, neuroanatomical, and cognitive alterations determined by genetic and environmental factors, which together show the underlying pathophysiology of the disease and vulnerability. Thus, their presence indicates an increased risk for the disease.43

Treatment of Depression in Patients with PsoriasisEffective management of psoriasis must be multidimensional and take into account the patient's psychological, social, and physical well-being. Prevention and prompt treatment of depression in these patients is important, not only to improve their quality of life but also because this treatment can help to improve the skin symptoms as well. Psychosocial support that helps to reduce distress or improve personal and interpersonal resources and work with families may also be beneficial for these patients.44 Anti-stigma interventions help to change attitudes in the population towards diseases that affect the patient's appearance and image.

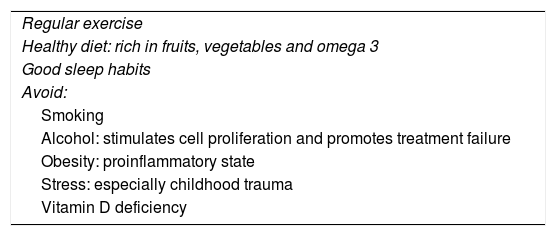

If we start from the premise that chronic systemic immune-inflammatory disorder is the critical point of connection between psoriasis and its comorbidities, the study of treatments designed to diminish the inflammatory immune response is justified. These include pharmacological treatments (such as cytokine antagonists [TNF inhibitors and IL-12 and 23 inhibitors] and celecoxib) as well as lifestyle changes that favor a healthier diet or reduce stress, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and substance abuse (Table 2).27,45–48

Healthy Habits That Reduce Inflammation and the Risk of Depression.

| Regular exercise |

| Healthy diet: rich in fruits, vegetables and omega 3 |

| Good sleep habits |

| Avoid: |

| Smoking |

| Alcohol: stimulates cell proliferation and promotes treatment failure |

| Obesity: proinflammatory state |

| Stress: especially childhood trauma |

| Vitamin D deficiency |

Source: Nasrallah, 201548

Neuroimmunology studies are giving rise to new pharmacological discoveries in psychiatric treatments. The use of anti-inflammatory agents alone or in combination with antidepressants is being investigated. While the results appear promising, most of these substances are still in preclinical studies.49

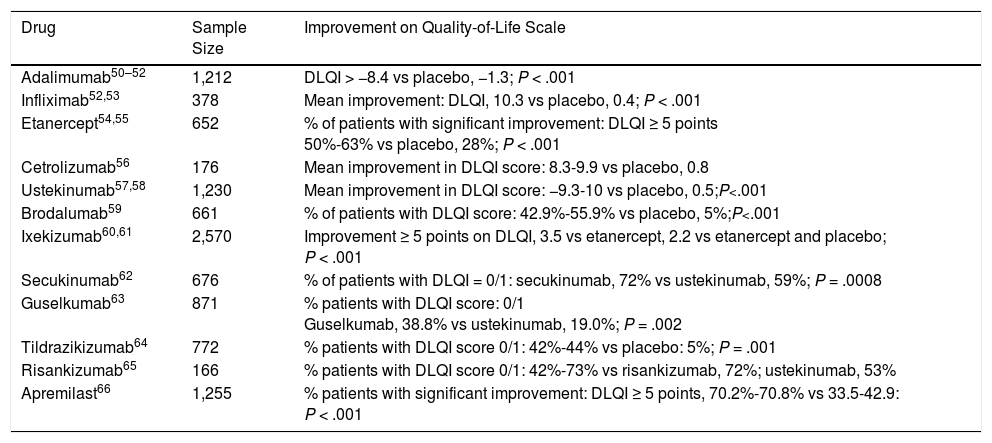

It would appear that biologic agents play an important role in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis and have a highly beneficial effect on quality of life in this setting (Table 3).

Impact of Biologic Therapy in Psoriasis Measured Using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).

| Drug | Sample Size | Improvement on Quality-of-Life Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Adalimumab50–52 | 1,212 | DLQI > −8.4 vs placebo, −1.3; P < .001 |

| Infliximab52,53 | 378 | Mean improvement: DLQI, 10.3 vs placebo, 0.4; P < .001 |

| Etanercept54,55 | 652 | % of patients with significant improvement: DLQI ≥ 5 points 50%-63% vs placebo, 28%; P < .001 |

| Cetrolizumab56 | 176 | Mean improvement in DLQI score: 8.3-9.9 vs placebo, 0.8 |

| Ustekinumab57,58 | 1,230 | Mean improvement in DLQI score: −9.3-10 vs placebo, 0.5;P<.001 |

| Brodalumab59 | 661 | % of patients with DLQI score: 42.9%-55.9% vs placebo, 5%;P<.001 |

| Ixekizumab60,61 | 2,570 | Improvement ≥ 5 points on DLQI, 3.5 vs etanercept, 2.2 vs etanercept and placebo; P < .001 |

| Secukinumab62 | 676 | % of patients with DLQI = 0/1: secukinumab, 72% vs ustekinumab, 59%; P = .0008 |

| Guselkumab63 | 871 | % patients with DLQI score: 0/1 Guselkumab, 38.8% vs ustekinumab, 19.0%; P = .002 |

| Tildrazikizumab64 | 772 | % patients with DLQI score 0/1: 42%-44% vs placebo: 5%; P = .001 |

| Risankizumab65 | 166 | % patients with DLQI score 0/1: 42%-73% vs risankizumab, 72%; ustekinumab, 53% |

| Apremilast66 | 1,255 | % patients with significant improvement: DLQI ≥ 5 points, 70.2%-70.8% vs 33.5-42.9: P < .001 |

Source: Adapted from Frieder et al67

Many studies have provided evidence of a significant improvement in affective symptoms following treatment with biologic agents. Ustekinumab improves the symptoms of depression and anxiety in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis.57

TNF-α inhibitors appear to have positive effects on mood and cognitive function, especially when inflammation levels are high.68,69 Although they do not cross the blood-brain barrier, these molecules appear to produce changes in cytokine expression by acting on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.70 The results of several studies have confirmed that TNF inhibitors decrease the severity of depressive symptoms independently of the severity of psoriasis.71 For example, in a large-scale, placebo-controlled study of etanercept in the treatment of psoriasis, patients who received the active drug showed a significant improvement in depressive symptoms compared to the control group independently of improvement in disease activity.72

Studies with infliximab have reported similar results, such as enhanced quality of life and improvements in other aspects of psoriasis and in the symptoms of depression in patients with Crohn disease.50,73,74

In the case of adalimumab, authors report improvements in physical functioning and the social and psychological aspects of psoriasis, with patients in some cases achieving quality-of-life scores higher than those of the general public.51 Several studies have provided evidence that adalimumab improves functioning, quality of life, and affective symptoms in these patients.74–77

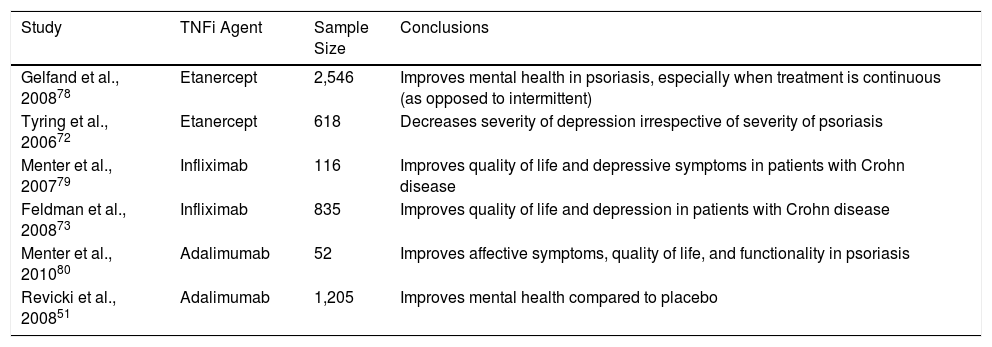

These drugs may represent an objective that can extend the boundaries of our approach to mental disorders. They appear to improve depressive symptoms in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, but the studies on this topic have limitations that must be overcome to confirm the evidence. The study populations were heterogeneous in terms of etiology, pathogenic mechanism, diagnosis, and comorbidities. Moreover, the use of several different diagnostic tools limits comparison between studies. Further studies are needed to determine what proportion of the improvement in depressive symptoms is due to improvement in the symptoms of psoriasis and how much can be attributed primarily to the drug itself (Table 4).

Studies on the Influence of Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors (TNFi) on Comorbid Depressive Symptoms.

| Study | TNFi Agent | Sample Size | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gelfand et al., 200878 | Etanercept | 2,546 | Improves mental health in psoriasis, especially when treatment is continuous (as opposed to intermittent) |

| Tyring et al., 200672 | Etanercept | 618 | Decreases severity of depression irrespective of severity of psoriasis |

| Menter et al., 200779 | Infliximab | 116 | Improves quality of life and depressive symptoms in patients with Crohn disease |

| Feldman et al., 200873 | Infliximab | 835 | Improves quality of life and depression in patients with Crohn disease |

| Menter et al., 201080 | Adalimumab | 52 | Improves affective symptoms, quality of life, and functionality in psoriasis |

| Revicki et al., 200851 | Adalimumab | 1,205 | Improves mental health compared to placebo |

Comorbid depression and psoriasis interrelate negatively, giving rise to a dangerous vicious circle. We can reduce the impact of depression by prompt diagnosis and treatment of the depression while alleviating the biopsychosocial impact of the skin disease.

The treatment of psoriasis with negative immune regulators is promising and offers an additional beneficial effect on psychiatric comorbidity, which is directly or indirectly associated with improvement in the skin disease. Most biologic drugs for psoriasis are only approved for use in moderate to severe disease. This indication gives rise to a new discussion about the definition of severity in psoriasis. Traditionally, severity was defined in terms of the intensity and extent of the psoriatic skin lesions. Today, however, other aspects, such as socioeconomic factors and the impact of psoriasis on the patient's physical and social activity and psychological and emotional state (which from the patient's perspective are the most important aspects) are becoming increasingly important.81 The inclusion of these factors in decision trees represents an advance in the comprehensive treatment of the disease.

Although we have considerable data on psychological comorbidity in psoriasis, much remains to be done. More multicenter studies are needed to clearly determine the pathophysiological mechanisms and would allow us to improve the detection and clinical management of comorbid psychiatric disease and the quality of life and prognosis of these patients.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: González-Parra S, Daudén E. Psoriasis y depresión: el papel de la inflamación. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:12–19.